Translate this page into:

3% Polidocanol Sclerotherapy for Pyogenic Granuloma: Efficacy and Safety Analysis

Address for correspondence: Dr. Ajay Jaywant Deshpande, Department of Dermatology, Maharashtra Medical Foundation, Joshi Hospital, 3, Surya Tower CTS No. 50-A, Erandwane, Pune 411004, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: deshpandeajay.68@gmail.com

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Introduction:

Pyogenic granuloma is a commonly occurring inflammatory hyperplasia involving skin and mucous membranes. Various modalities of treatment have been used to treat pyogenic granuloma. However, there is an increased risk of intraoperative bleeding and recurrence of pyogenic granuloma following surgical treatment of pyogenic granuloma. Therefore, sclerotherapy has evolved as an effective alternative treatment modality in excellent safety and efficacy.

Aims and Objectives:

The aim of this study was to assess the safety and efficacy of 3% polidocanol in liquid form in pyogenic granuloma as a sclerosant.

Settings and Design:

This was a retrospective study of cases treated between March 2019 and February 2020 at two different private institutes.

Materials and Methods:

The study included 30 patients with 30 pyogenic granulomas treated with 3% polidocanol liquid. Individuals with comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, thyroid disorders, and those who were on medications were excluded from the study. Two units of 3% polidocanol solution were injected with an insulin syringe at the base of the lesion. Changes in lesions and adverse events were recorded and injections were repeated after a gap of 2 weeks if needed.

Result:

In 28 patients, there was complete resolution of the lesion within 4 weeks and 2 patients received a second injection of polidocanol. All the patients tolerated the procedure and the lesions resolved without any significant sequelae.

Discussion:

The advantages of 3% polidocanol sclerotherapy are that it is a safe, easy, effective, and minimally invasive procedure with little discomfort to the patient and very minimal complications as compared with other modalities.

Conclusion:

Polidocanol 3% solution is an effective sclerosant for the treatment of pyogenic granuloma.

The aim of this study was to assess the safety and efficacy of 3% polidocanol in the liquid form in PG as a sclerosant.

Keywords

Polidocanol

pyogenic granuloma

sclerotherapy

BACKGROUND

Pyogenic granuloma (PG), also known as lobular capillary hemangioma, is an exaggerated, reactive proliferation of granulation, and vascular tissue.[123] It occurs at any age and is often stimulated by minor injury or infection. PG usually presents as a solitary, red, rapidly growing papule, or nodule, often with a subtle collarette of scale.[45] It often develops an eroded surface, with subsequent bleeding that can be profuse.

PG does not involute spontaneously and various modalities of treatments including conservative surgical resection[6] or laser surgical excision,[7] radiofrequency coagulation,[7] cryotherapy,[8] imiquimod cream,[9] alitretinoin gel,[10] topical timolol,[11] and chemical cauterization[12] have been used with variable results. However, there is an increased risk of intraoperative bleeding, postoperative infection, and recurrence of PG with these modalities.[13] In cases where PG is large or occurs in a surgically difficult area, choosing an appropriate treatment modality can be difficult. Therefore, sclerotherapy is considered as an alternative and effective treatment modality, as it is a simple and noninvasive procedure with a better safety profile, repeatability, and low cost of treatment even when multiple sessions are needed with a low recurrence rate.[1415] Polidocanol is a well-established sclerosing agent already used for chronic venous disease[1617] and bleeding esophageal varices.[18] Rao et al.[19] found less side effects (ulceration and swelling) with polidocanol than sodium tetradecyl sulfate (STS) in a prospective comparative trial for leg veins. Polidocanol 2% foam has been successfully used for the treatment of children with PG.[20]

Aims and objectives

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study included 30 patients (18 men and 12 women) with 30 PG who were treated between March 2019 and February 2020. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The age of patients ranged from 11 to 35 years. The mean age was 26 years. Eight lesions were found on fingers, two on the palmer aspect of the hand, six on the face (eyelid, upper lip, and beard), two on the scalp, seven on the forearm, and five on the thigh. Individuals with comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, thyroid disorders, and those who were on medications such as digoxin, carbimazole, furosemide, and captopril were excluded from the study. Pregnant and lactating women were also excluded from the study.

Using an insulin syringe, two units (equivalent to 0.05 mL) of 3% polidocanol was injected slowly into the base of the lesion, irrespective of the lesion size, until blanching was observed. Local anesthesia was not used and no dressing was provided after injection. Patients were followed up weekly until the lesions became necrotic and fell off spontaneously. Changes in lesions and adverse events were recorded and injections were repeated after a gap of 2 weeks if needed. Nine patients needed the second dose of two units of 3% polidocanol after 2 weeks.

The efficacy of treatment was noted according to physical examination and follow-up evaluation as well as photographic comparison at 2, 4, and 12 weeks after the treatment.

RESULTS

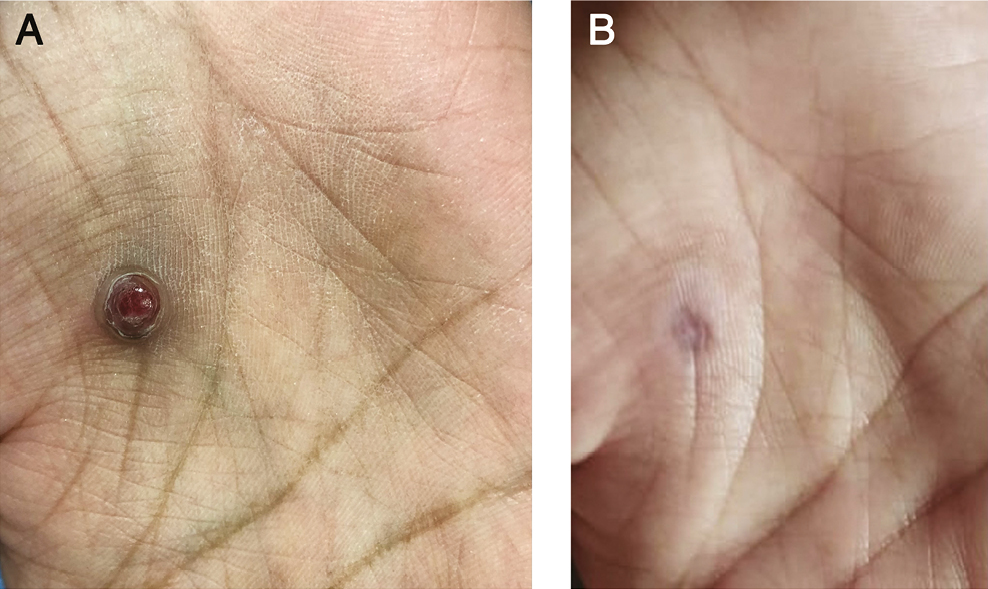

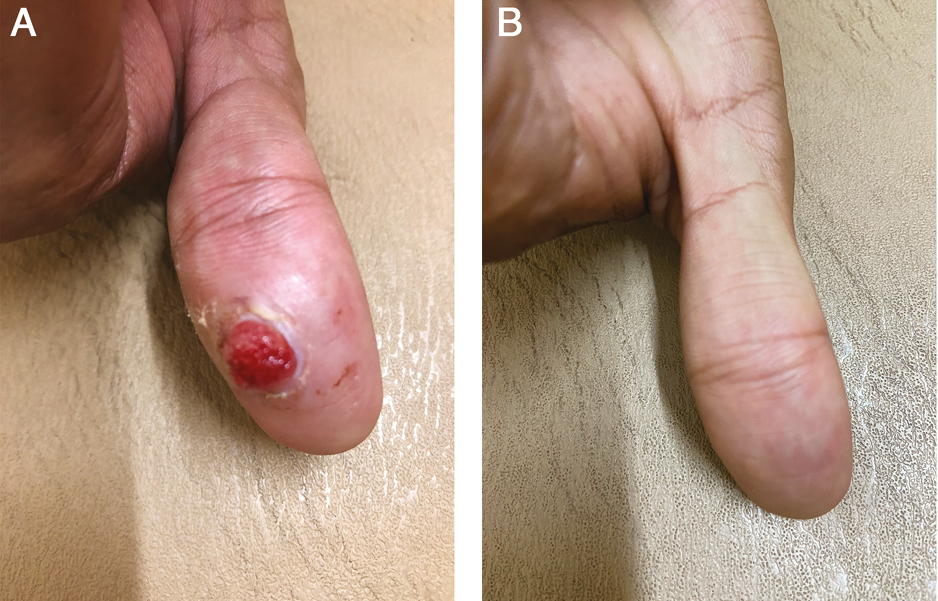

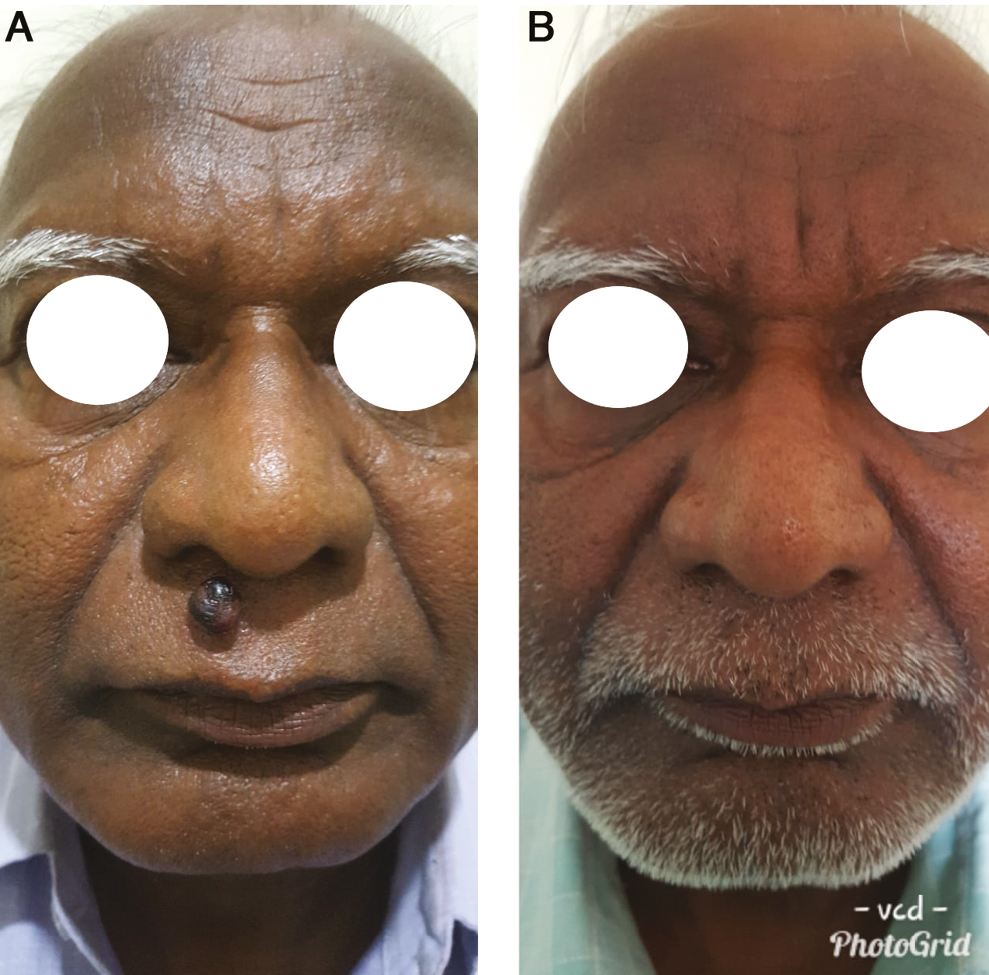

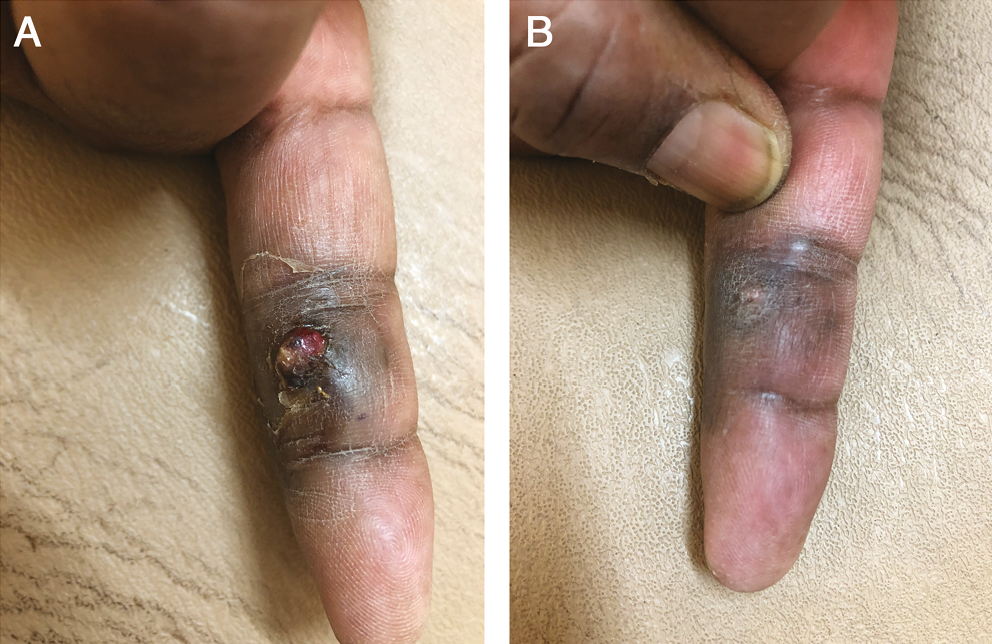

In 28 patients, there was complete resolution of the lesion within 4 weeks of therapy with inconspicuous scars [Figure 1A and B]. Most of the lesions healed without any pigmentary changes or scarring [Figure 2A and B] [Figure 3A and B]. In one of the patients, there was healing with post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation [Figure 4A and B]. Of these 28 patients, nine patients were given the second injection of polidocanol 2 weeks after the first dose; the total volume of drug injected was 0.1 mL in two sessions. However in the remaining 19 patients, the single dose of polidocanol (total dose of 0.05 mL) was sufficient for the complete resolution of the lesion. The procedure was well tolerated and there was no recurrence. No adverse effects were found in the form of allergic reactions and cutaneous necrosis. Mild injection pain was experienced by the patient at the time of the procedure. In two patients, a residual lesion of around 6 mm persisted, which was dealt with coagulation with radiofrequency under local anesthesia as patients were reluctant for further sclerotherapy treatment. Anaphylaxis, tissue necrosis, ulceration, and scarring were not seen in our study. Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation was noted in one case having a lesion over the finger, which was resolved completely within 6 weeks without any treatment.

- (A) Before treatment. (B) After 1 session

- (A) Before treatment. (B) After 1 session

- (A) Before treatment. (B) After 2 sessions

- (A) Before treatment. (B) After 2 sessions

DISCUSSION

Sclerotherapy is the targeted elimination of small vessels and vascular anomalies by the injection of a sclerosant.[21] These are tissue irritants causing vascular thrombosis and permanent damage to the endothelial vessels resulting in endofibrosis and vascular obliteration when injected into or adjacent to blood vessels.[22] The most commonly used sclerosants are polidocanol, STS, sodium morrhuate, sodium sylliate, pingyangmycin, OK-432, ethanolamine oleate, and ethanol.[23]

Polidocanol (hydroxy-polyethoxy-dodecane) is a synthetic long-chain fatty alcohol.[24] The drug, originally developed and marketed as a local anesthetic, was first used as a sclerosing agent in Germany in the 1960s. Polidocanol is painless on injection, does not produce necrosis if injected intradermally, and has been reported to have a very low incidence of allergic reactions.[24] The drug has been extensively studied and has a high therapeutic index.[252627] Occasionally, anaphylactic reactions have been reported with polidocanol use in treating esophageal varices[28] and leg veins,[29] wherein the dose required is much higher than that is required for treating PG (0.05 mL). In this study, the author did not come across any such incidence. In some patients, it may produce hyperpigmentation and it is also observed in our study that it resolves within 6 weeks without any treatment. Hyperpigmentation is more common with other sclerosing agents than polidocanol and therefore aesthetically more acceptable especially treating facial lesions.[30] In a study by Rao et al.,[19] tissue necrosis and ulceration were found to be more common with STS than with polidocanol and in our study also we did not come across such complications. Anesthesia (surface or local) is required before injecting sclerosants such as STS or ethanolamine oleate, whereas polidocanol being itself a local anesthetic[24] has added advantage as a sclerosant over others.

Various authors[23] have emphasized the effectiveness of sclerotherapy using 3% STS in the management of PG involving various anatomical locations including orogingival locations and of various sizes and surgically inaccessible locations. Polidocanol, which is used as a sclerosant in the PG, is a newer agent and has successfully been used by Carvalho et al.,[20] wherein a diluted solution of 2% polidocanol in 1:3 proportion with a physiological solution was used. The total mean dose of 1.21 mL required was much higher (10 times) than that is required in our study without any adverse effects. Also, in our study, using 3% of the drug, only two patients needed the second injection of sclerosant, whereas two or three injections were needed with 2% of diluted solution of polidocanol leading to decrease compliance of the patient.

The management of PG depends on the clinical scenario. Several studies showed that sclerotherapy should be considered as an effective treatment approach for PG irrespective of size and location.[1415] Most of these studies suggested sclerotherapy using 2% polidocanol in dilution, whereas in this study the author used 3% undiluted polidocanol successfully without compromising the safety profile with faster recovery and better compliance.

The advantages of 3% polidocanol sclerotherapy are that it is a safe, easy, effective, and minimally invasive procedure with little discomfort to the patient and very minimal complications as compared with other modalities. There was negligible blood loss and no requirement for any postoperative dressing or specific care. In this study, no postoperative complications were observed, except for local discomfort that resolved within few minutes.

CONCLUSION

Sclerotherapy is proven to be a valid treatment option with significant clinical benefits. Polidocanol is found to be superior in safety and efficacy in the management of PG occurring at various anatomical locations with practically no recurrence rate with quick response.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

REFERENCES

- Lobular capillary hemangioma: The underlying lesion of pyogenic granuloma. A study of 73 cases from the oral and nasal mucous membranes. Am J Surg Pathol. 1980;4:470-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vascular tumours and tumour-like conditions of blood vessels and lymphatics. In: Elder D, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL, eds. Lever’s histopathology of the skin (9th ed). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 2005. p. :1015-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Familial generalized multiple glomangiomyoma: Report of a new family, with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:402-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): A clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trap technique for bloodless removal of digital pyogenic granuloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e109-e10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic approaches to pyogenic granuloma: An updated review. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:642-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cryotherapy in the treatment of pyogenic granuloma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:788-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pyogenic granuloma in 10 children treated with topical imiquimod. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:269-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- The efficacy of silver nitrate cauterization for pyogenic granuloma of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28:435-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical inquiries: What’s the best treatment for pyogenic granuloma? J Fam Pract. 2010;59:40-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful treatment of pyogenic granuloma with sclerotherapy. Indian J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;5:30-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sclerotherapy for the treatment of pyogenic granuloma. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:77-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- European guidelines for sclerotherapy in chronic venous disorders. Phlebology. 2014;29:338-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sclerotherapy for low-flow vascular malformations of the head and neck: A systematic review of sclerosing agents. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:295-304.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative histologic studies following esophageal varices sclerosing with different substances. Leber Magen Darm. 1983;13:215-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Double-blind prospective comparative trial between foamed and liquid polidocanol and sodium tetradecyl sulfate in the treatment of varicose and telangiectatic leg veins. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:631-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polidocanol sclerotherapy for the treatment of pyogenic granuloma. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1068-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sclerotherapy in pyogenic granuloma and mucocele. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2018;30:230-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Technology assessment committee: Sclerosing agents for use in GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosec. 2007;66:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sclerotherapy: A novel modality in the management of oral pyogenic granuloma. Indian Soc Periodontol. 2021;25:162-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sclerosing solutions. In: Bergan JJ, ed. The vein book (1st ed). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2007. p. :125-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improper potency and impurities in compounded polidocanol. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:1124-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- An evidence-based review of off label- uses of polidocanol. Curr Clin Phamacol. 2017;12:223-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subcutaneous injection of large volumes of polidocanol. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:476-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic treatment of esophagogastric varices. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 1992;55:251-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of reticular and telangiectatic leg veins: Double-blind, prospective comparative trial of polidocanol and hypertonic saline.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complications and adverse sequelae of sclerotherapy. In: Goldman MP, Weiss RA, eds. Sclerotherapy (6th ed). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017. p. :200-61.

- [Google Scholar]