Translate this page into:

Intralesional Bleomycin in Lymphangioma: An Effective and Safe Non-Operative Modality of Treatment

Address for correspondence: Professor AN Gangopadhyay, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, 221005, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: gangulybhu@rediffmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

Lymphangiomas are benign hamartomatous lymphatic tumors. The mainstay of the therapy is surgical excision, but due to its infiltration along the nerves and muscles, total excision is not always possible. In the present study, we have evaluated the clinical profile of all the cases of lymphagiomas coming to our department and evaluated the efficacy of intralesional Bleomycin as a sclerosing agent in its management.

Materials and Methods:

In this prospective study, all patients were evaluated clinically and color Doppler ultrasonography (USG). The required dose was calculated as 0.5 mg/kg body weight, not exceeding 10 units at a time. The response was assessed clinically and on the basis of color Doppler USG.

Results:

Thirty-five patients of lymphangioma were included in the study. The neck region was the most common site of involvement. The response was excellent in 7 (20%), good in 26 (74.29%), and poor in 2 (5.71%) patients. The complications included fever, transient increase in size of swelling, local infection, intraluminal bleed, and skin discoloration in 10 patients.

Conclusion:

This therapy may be used as primary modality instead of surgery in selected group of patients.

Keywords

Bleomycin

intralesional bleomycin

lymphangioma

surgery

INTRODUCTION

Lymphangiomas are benign hamartomatous lymphatic tumors, characterized by multiple communicating lymphatic channels and cystic spaces. They occur in nearly all regions of the body but are most frequently seen in neck (75%), axilla (20%), and inguinal areas (2%).[1]

Most of them are evident at birth (65%), while the remainders become evident by the age of 2 years.[2] The reported incidence is quite variable, ranging between 1 in 1000 and 16000 live births.[34]

The mainstay of the therapy is surgical excision, but due to its infiltration along the nerves and muscles, total excision is not always possible. The extensive surgery may sometime lead to disfigurement, damage to vital structures, and ugly scar. To avoid the morbidity associated with surgical excision, injection of sclerosing agents has long been used. In the past, boiling water, 50% dextrose, hypertonic saline, or absolute alcohol has been used. The results were not very encouraging. With the advent of agents like Bleomycin, acetic acid, OK-432, Doxycycline, many centers are using them as first line of therapy with satisfactory results.[5]

In the present study, we have evaluated the clinical profile of all the lymphagioma cases coming to our department and evaluated the efficacy of intralesional Bleomycin as a sclerosing agent in its management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a prospective study from July 2009 to June 2011 conducted in the Department of Pediatric Surgery of the University Hospital. It was approved by the Institute ethical committee. The parents were informed about the study and a written consent was taken from them.

All patients coming to the department were included in the study. The exclusion criteria were lesions infiltrating the mediastinum, lesions around trachea, frank infection, and deep retroperitoneal lesions.

All patients had a detailed clinical evaluation, along with pre-treatment clinical photograph.

Color Doppler ultrasonography (USG) of all patients was performed. The volume of lymphangiomas was calculated by the following formula-

Length × breadth × depth × 0.52 cc, where 0.52 is correction factor.

Based on color Doppler USG report, the lesions were classified as:

-

Lymphangioma simplex (composed of capillary sized thin walled lymphatic channels)

-

Cystic lymphangioma or cystic hygroma

-

Cavernous lymphangioma (dilated lymphatic channel with a fibrous adventitial covering) (mixed forms also exist).

Procedure- 1 unit of Bleomycin is equivalent to 1 mg. The required dose was calculated as 0.5 mg/kg body weight, not exceeding 10 units at a time. The patient was then taken in O.T. and sedated either by oral chloral hydrate or intravenous (IV) diazepam.[6] The fluid of the lymphangioma was aspirated as much as possible with a 10 ml disposable syringe. After that, bleomycin was injected intralesionally in a ratio of 5:1 (aspirated volume: bleomycin volume). The patient was kept under observation till evening. If fever occurred, oral paracetamol was prescribed. Patients were called after 4 weeks for evaluation of the response in the proforma and clinical photograph. If needed, repeat color Doppler USG was performed for estimation of its volume and comparison with the previous USG. If regression was not complete, another dose of freshly reconstituted bleomycin was injected in the same manner.

The patients were called monthly for follow up. Bleomycin was stopped when the swelling disappeared clinically, on the basis of color Doppler USG, or there was no response or the swelling became stationary. The patients were subjected to surgery when there was no response or the swelling became stationary even after three to four injections.

The response was assessed clinically and on the basis of color Doppler USG as:

-

Excellent - complete regression without induration

-

Good - >50% regression

-

Poor - <50% regression

The statistical method used was the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test. The P value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

During the study period of 2 years, 35 patients of lymphangioma were included in the study. Nineteen (54.2%) patients were seen before 1 year of age. Ten (28.5%) patients presented between 1 to 2 years of age. Only six (17.14%) patients presented after 2 years. Of the 35 cases, 28 (80%) were cystic hygroma, 1 (2.86%) cavernous, and 6 (17.14%) were of mixed type.

The neck region was the most common site with 22 (62.86%) patients, followed by face with 7 (20%), 3 (8.57%) in chest wall, 2 (5.71%) in axilla, and 1 (2.86%) in buttock and thigh.

Out of the 35 patients included in the study, 7 (20%) required single dose, 29 (57.14%) required two doses, 2 (5.71%) required three doses, 4 (11.42%) required four doses, and 2 (5.71%) required five doses of intralesional bleomycin. Lesions that could be aspirated completely required less number of total doses because more bleomycin per unit surface area was available for action.

The response was excellent in 7 (20%), good in 26 (74.29%), and poor in 2 (5.71%) patients. Out of 28 patients of cystic hygroma, 7 (25%) showed excellent response, 20 (71.42%) showed good response, and 1 (3.57%) showed poor response. The cavernous variety showed good response (100%). Out of six patients of mixed variety, five (83.33%) showed good response and one (16.67%) showed poor response [Figures 1–3].

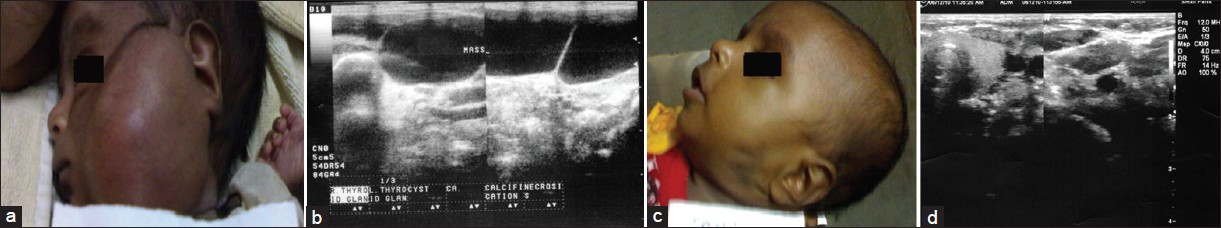

- Huge cystic hygroma before intralesional bleomycin. The same lesion has considerably reduced after the injection

- (a) Cystic hygroma before intralesional bleomycin. (b) On color Doppler, large multiloculated cystic mass with mild septal vascularity measuring 120 ml, is noted on the left side of face. (c) Reduction in size after intralesional bleomycin. (D) After intralesional bleomycin, on color Doppler, fibrous tissue without any residual cyst is noted

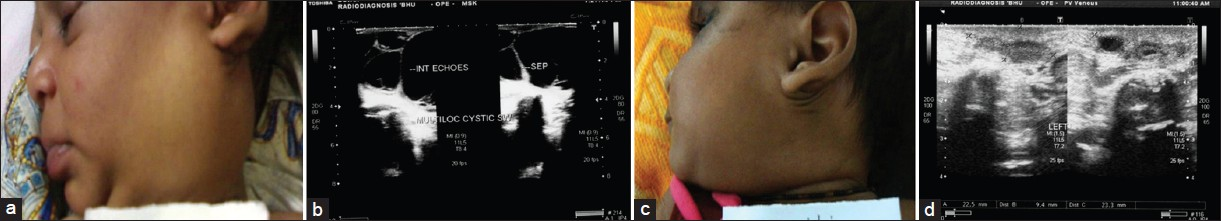

- (a) Cystic hygroma before intralesional bleomycin. (b) On color Doppler, the cystic mass measured approximately 45 ml. (c) Reduction in size after intralesional bleomycin. (d) On color Doppler, irregular cystic mass in noted on the left side of neck with fibrosis measuring 3 ml

The Wilcoxon signed rank test was applied to compare the initial and final volume. The initial volume was 126.07±40.01 and the final volume was 25.68±18.01. After applying the Wilcoxon signed ranks test, the P value was <0.001, which is highly significant.

Out of the 10 patients who developed side effects, 3 (30%) developed fever, 3 (30%) had transient increase in size of swelling, 2 (20%) developed local infection, 1 (10%) developed intraluminal bleed, and 1 (10%) showed skin discoloration. Out of the 26 patients in the good response group, three underwent surgery after completion of sclerotherapy for cosmetic purpose and two patients of the poor response group underwent surgery.

DISCUSSION

The reported incidence of these tumors in the literature is quite variable, ranging from 1 in 1000 to 16000 live births.[34] Lymphangioma are thought to arise from a combination of the following: a failure of lymphatics to connect to the venous system, abnormal budding of lymphatic tissue, and sequestered lymphatic rests that retain their embryonic growth potential. These lymphatic rests can penetrate adjacent structures or dissect along fascial planes and eventually become canalized. These spaces retain their secretions and develop cystic components because of the lack of a venous outflow tract. The nature of the surrounding tissue determines whether the lymphangioma is capillary, cavernous, or cystic.

Cystic hygroma tend to form in loose areolar tissue, whereas capillary and cavernous forms of lymphangiomas tend to form in muscle.[4] At present, complete excision remains the treatment of choice for lymphangioma. For complex lymphangioma, complete removal may require multiple operations and may not be possible without damaging adjacent vital structures.[7] The complications from the surgical excision of a lymphangioma are related to the location and structures adjacent to the mass; these include damage to a neurovascular structure (including cranial nerves), chylous fistula, chylothorax, hemorrhage, and recurrence. Most recurrences occur within the first year but have been reported to occur as long as 10 years after excision. Unlike in hemangiomas, spontaneous resolution of lymphangioma is uncommon. Recurrence is rare when all gross disease is removed. If residual tissue is left behind, the expected recurrence rate is approximately 15%.[8] Postoperative complications, including recurrence, wound seromas, infection, and nerve damage, occur in 30% or more of cases. Recurrence rates vary depending on the complexity of the lesion and the completeness of excision.

Complete surgical resection may be difficult due to the presence of multiple loculations and extensive disease. Sclerotherapy provides a treatment option in such patients, offering a viable alternative to surgery in patients with macrocystic lymphatic malformations (LM). Although the popularity of sclerotherapy in the treatment of LM is growing, there is no consensus regarding the type of sclerosant. This is largely due, in part, to a lack of understanding on sclerosant mechanism of action.[29]

Umezawa first developed bleomycin as an antitumor agent in 1966 and its mechanism of action was by inhibition of DNA synthesis.[10] This drug was also known to produce a sclerosing effect due to its direct action on the endothelial cells producing non-specific inflammatory reaction. Desired effect of sclerosis is achieved by local action of bleomycin, which depends on availability of drug per unit surface area of lesion.[1112]

Side effects of Bleomycin are fever, transient increase in size of swelling, hemorrhage, leukocytosis, infection, and pulmonary fibrosis. Pulmonary fibrosis has been associated with intravenous bleomycin administration exceeding the total cumulative dose of 400 mg. Bleomycin doses used in sclerotherapy are small in comparison, typically 1% to 5% of the lowest dose associated with possible pulmonary fibrosis.[13] We used 0.5 mg/kg of dose. Others have used it in doses ranging from 0.3 to 3 mg/kg.[91415] In this study, complications were noted in 10 (28.5%) patients, which is less than some studies where complications were noted in about 43% of patients.[14] Others have noted fewer complications as compared to this study.[1617]

Although surgical excision has been considered to be treatment of choice by most of the surgeons but it is associated with tedious dissection along with lot of morbidity in the form of disfigurement and damage to vital structures and ugly scar. Therefore, sclerotherapy of lymphangioma has gained popularity during recent years. In this prospective study, we found the response satisfactory in almost 95% of cases (Excellent in 20% and Good in 74.29%). Others have also got good response using bleomycin. Rozman et al noted excellent and good response in 63% (15/24) of lesions and 21% (5/24) patients.[16] Niramis et al noted 83% of response where as Baskin et al noted about 95% of response, suggesting good activity of bleomycin for the purpose.[914] In short term follow up no recurrence was encountered. Others have also not found recurrence to be of much concern.[15–17] Although mortality has been reported,[14] it was not seen in this series.

To conclude, use of bleomycin as an intralesional agent for lymphagioma appears to be safe and rewarding. This therapy may be used as primary modality instead of surgery in selected group of patients.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- The lymphatic system in human embryos, with a consideration of the morphology of the system as a whole. Am J Anat. 1909;9:43-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- New treatment options for lymphangioma in infants and children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111:1066-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hemangiomas, cystic hygromas, and teratomas of head and neck. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1994;3:147-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment options for the management of vascular malformations. In: Waner M, Suen JY, eds. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations of the head and neck. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1999. p. :315-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Handbook of Dermatologic Drug Therapy. London, UK: Taylor and Francis; 2005.

- Surgical treatment of cervicofacial cystic hygromas in children. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2005;67:331-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic factors in the treatment of lymphatic malformations. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:1061-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Local bleomycin injection in the treatment of lymphangioma. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2005;15:383-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent study on biochemistry and action of Bleomycin. In: Carter SK, Crook ST, Umezawa H, eds. Bleomycin: Current Status and New Developments. New York NY: Academic Press; 1978. p. :15-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- In Injection of beomycin as a primary therapy of the cystic lymphangioma. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:440-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bleomycin as intralesional sclerosant for cystic hygromas. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2004;9:3-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of cystic hygroma by intralesional bleomycin injection: Experience in 70 patients. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2010;20:178-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymphangioma: Is intralesional bleomycin sclerotherapy effective? Biomed Imaging Interv J. 2011;7:e18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intralesional bleomycin injection treatment for vascular birthmarks: A 5-year experience at a single United Kingdom unit. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:2031-44.

- [Google Scholar]