Translate this page into:

Chemical Leucoderma Induced by Ear-ring Stoppers Made of Polyvinyl Chloride

Address for correspondence: Dr. Archana Singal, B-14 Law Apartments, Karkardooma, Delhi – 110092, India. E-mail: archanasingal@hotmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

We report a case of chemical leucoderma (CL) in a 15-year-old girl, who developed patterned depigmentation at the back of both ear lobules after contact with plastic ear-ring stoppers made of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) after continuous use for 6–7 months. Patch test with Indian standard series and cosmetic series was negative after 48 h, but she refused patch testing for extended duration as the possibility of induced depigmentation at the test site was unacceptable to her. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of plastic ear-ring stopper induced CL.

Keywords

Chemical leucoderma

contact depigmentation

plastic ear-ring stoppers

PVC

INTRODUCTION

Chemical leucoderma (CL) occurs after repeated topical or systemic exposure to a variety of chemicals, usually without preceding inflammation.[1] The majority of these chemicals are aromatic or aliphatic derivatives of phenols and catechols.[2] Herein, a case of CL secondary to ear-ring stoppers made of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is illustrated.

CASE REPORT

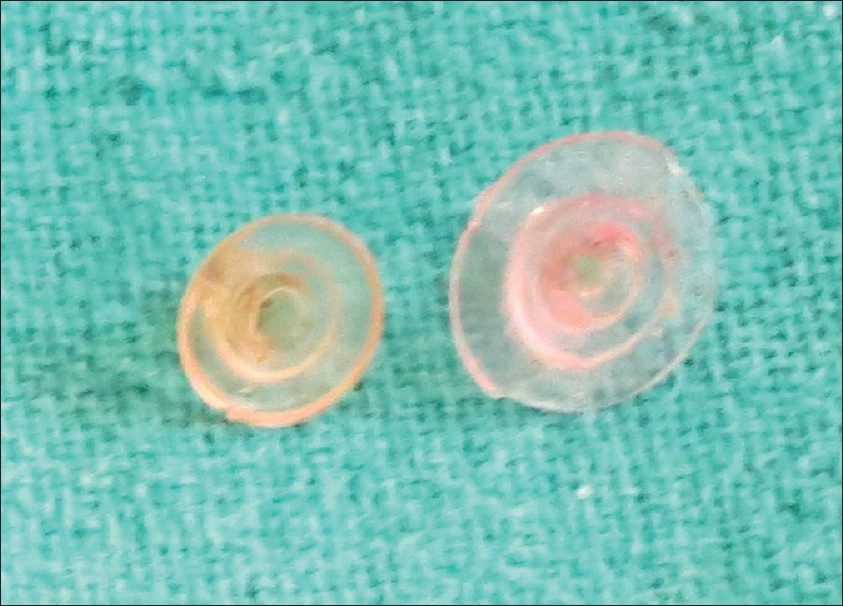

A 15-year-old girl presented with a patterned depigmentation over the back of both ear lobules of 2 months duration. She had been using plastic ear-ring stoppers for approximately 6 months. There was no history of preceding erythema or itching. She refused previous history of spontaneous depigmented lesions on her body or in family members. Examination revealed well-defined circular areas of depigmentation, symmetrically involving back of both ear lobules and extending to the immediate retroauricular region, with no signs of inflammation or change in skin texture [Figure 1]. The location of the lesions almost corresponded to the site of contact of the plastic ear-ring stoppers [Figure 2].

- Patterned circular area of depigmentation over the back of left ear lobule

- Plastic ear-ring stoppers made of polyvinyl chloride

Standard patch testing was done with the Indian standard series and cosmetic series of allergens (Chemotechnique), approved by the Contact and Occupational Dermatoses Forum of India. It was negative after 48 h. The patient refused patch testing for extended duration for fear of possible induced depigmentation at the patch test site. She was started on topical 0.1% tacrolimus cream, but unfortunately she was lost to follow-up.

DISCUSSION

In a clinic-aetiological study of 864 cases, the aetiological agents causing CL identified were: hair dye 27.4% (21% self-use, 6.4% not self-use), deodorant and spray perfume 21.6%, detergent and cleansers 15.4%, adhesive bindi 12%, rubber chappal 9.4%, black socks and shoes 9.1%, eyeliner 8.2%, lip liner 4.8%, rubber condoms 3.5%, lipstick 3.3%, fur toys 3.1%, toothpaste 1.9%, insecticides 1.7%, “alta” 1.2%, and amulet string colour 0.9%. Therapeutic response was much better in “pure” CL (73.4%) than in those with co-existing vitiligo (20.9%).[3] CL may pose a diagnostic dilemma as clinicopathological criteria do not reliably differentiate CL from vitiligo. Nevertheless, a history of repeated exposure to a known or suspected depigmenting agent is often useful.[4] Genetically determined fragility of melanocytes is speculated to be the key mechanism. Unlike idiopathic vitiligo, predisposing factors are implicated in CL, which initiate programmed cell death or apoptosis of melanocytes.[5] Genetic inability of melanocytes to tolerate and/or respond to oxidative stress may be the underlying molecular mechanism in CL.[5] To facilitate the diagnosis of CL, clinical diagnostic criteria have been proposed,[5] according to which any three out of the following four should be present: a) acquired vitiligo-like lesions, b) history of repeated exposure to specific chemical compounds, c) patterned vitiligo-like macules conforming to the site of exposure and d) confetti macules. Our case met the first three criteria and hence labelled as a case of CL. CL may occur at patch test sites, and patch test results may not always be positive in cases of CL. In a study of 50 patients of contact leucoderma, positive patch test reactivity with offending agent was seen in 18 (36%) and depigmentation was seen in only 4 (8%) cases after 21 days of patch testing.[6]

PVC content in the stoppers was confirmed from the manufacturer. PVC, an inexpensive thermoplastic, is a widely used plastic. It is made by polymerisation of the vinyl chloride monomer. The final PVC products, when completely cured or hardened, are generally considered to be inert and non-hazardous to the skin. However, there are a number of additives included in the final PVC products such as plasticisers and stabilisers, as well as molecules of the monomer. Di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DOP), butyl benzyl phthalate and di-N-butyl maleate are used as plasticisers for soft PVC.[7] These plasticisers are known to cause contact dermatitis and contact urticaria. However, after a meticulous search on PubMed and Medline, only three reports of PVC-induced CL have been found. Kim et al.[7] reported CL with oxygen nasal cannula containing both PVC and plasticisers like DOP, dibutyl phthalate and diethyl phthalate. Frenk and Kocsis[8] reported a case of depigmentation from adhesive tape made of PVC with a natural rubber adhesive base that contained a derivative of dihydroxydiphenyl methane. Stethoscope earpiece containing PVC and phthalates has been reported to induce contact depigmentation.[9] It would have been interesting to know what plasticisers were used in its manufacture, but the facility was not available in our institution. Though the exact mechanism of PVC-induced depigmentation is not known, it has been mooted that PVC causes CL following prolonged contact.

Treatment options of CL include discontinuation of the offending agent, topical steroids, tacrolimus, oral steroid pulse, phototherapy (narrow band-UVB, PUVA), etc.[10] Resistant cases needs to be managed surgically. Techniques of surgical repigmentation involve the transfer of melanocytes, melanocytes and keratinocytes, or full-thickness skin from normally pigmented areas to hypomelanotic patches. Autologous skin grafts can be divided into three major groups: (1) grafting of normal skin (epidermis with or without dermis) that contains melanocytes, (2) grafting of a noncultured epidermal or hair follicle suspension that contains melanocytes, and (3) grafting of cultured melanocytes with or without keratinocytes, in suspension or as sheets.[11] In this case, the patient was advised to use the metallic stoppers instead of the PVC ear-ring stoppers.

PVC ear-ring stoppers are in vogue among girls/women as a substitute to the precious and expansive metals like gold or silver. This is the first report of CL induced by plastic ear-ring stoppers. In future, with increasing use of PVC ear-ring stoppers in precious as well as imitation jewellery, dermatologists are more likely to encounter this patterned depigmentation, and therefore it is imperative to take cognisance of this new pattern and cause of CL.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- Paraesthesias due to contactants. In: Rietschel RL, Fowler JF, eds. Fisher's contact dermatitis (6th ed). Ontario: BC Decker Inc; 2008. p. :470-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contact depigmentation induced by propyl gallate. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:366-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical leucoderma: A clinico-aetiological study of 864 cases in the perspective of a developing country. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:40-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical leukoderma: What's new on etiopathological and clinical aspects? Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:255-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contact vitiligo: Etiology and treatment. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:27-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depigmentation dye to adhesive tape: Ultrastructural comparison with vitiligo and vitiliginous depigmentation associated with a melanoma. Dermatologica. 1974;148:284.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stethoscope earpiece-induced chemical depigmentation. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:110-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical leucoderma: Indian scenario, prognosis, and treatment. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:250-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- New and experimental treatments of vitiligo and other hypomelanoses. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:393-400.

- [Google Scholar]