Translate this page into:

A Comparison of Low-Fluence 1064-nm Q-Switched Nd: YAG Laser with Topical 20% Azelaic Acid Cream and their Combination in Melasma in Indian Patients

Address for correspondence: Dr. Charu Bansal, F-124/A, Dilshad Colony, Delhi, India. E-mail: drcharu2009@gmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Melasma is an acquired symmetric hypermelanosis characterised by irregular light to gray-brown macules on sun-exposed skin with a predilection for the cheeks, forehead, upper lip, nose and chin. The management of melasma is challenging and requires meticulous use of available therapeutic options.

Aims:

To compare the therapeutic efficacy of low-fluence Q-switched Nd: YAG laser (QSNYL) with topical 20% azelaic acid cream and their combination in melasma in three study groups of 20 patients each.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty Indian patients diagnosed as melasma were included. These patients were randomly divided in three groups (group A = 20 patients of melasma treated with low-fluence QSNYL at weekly intervals, group B = 20 patients of melasma treated with twice daily application of 20% azelaic acid cream and group C = 20 patients of melasma treated with combination of both). Study period was of 12 weeks each. Response to treatment was assessed using melasma area and severity index score.

Statistical Analysis:

The statistical analysis was done using Chi-square test, paired and unpaired student t-test.

Results:

Significant improvement was recorded in all the three groups. The improvement was statistically highly significant in Group C as compared to group A (P < 0.001) and group B (P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

This study shows the efficacy of low-fluence QSNYL, topical 20% azelaic acid cream and their combination in melasma. The combination of low-fluence QSNYL and topical 20% azelaic acid cream yields better results as compared to low-fluence QSNYL and azelaic acid alone.

Keywords

Azelaic acid

low-fluence laser melasma

Q-switched Nd-YAG laser

INTRODUCTION

Melasma is characterised by ill-defined brownish macules on the face. It is a common pigmentary disorder and is known to occur in all skin types and all ethnic groups. Nevertheless, it is far more prevalent in dark complexion races that live in areas of intense UV radiations such as Asians, Latin Americans and Blacks.[1] The implicated factors in causation of melasma include pregnancy, cosmetics, genetic factors, endocrine factors, vascular factors and hormonal therapy.[2–4] These factors eventually lead to an increased synthesis of melanosomes in melanocytes and increased transfer of melanosomes to keratinocytes.[5] The condition is benign though psychologically disturbing.

Three clinical patterns of melasma are known: Centrofacial (most common), malar and mandibular.[6] Further, based on visible light, Wood's light examination and skin histology, melasma can be divided into three types. Epidermal type has increased melanin predominantly in the basal and suprabasal epidermis with pigment accentuation on Wood's lamp. The dermal variant has melanin-laden macrophages in the perivascular distribution in the superficial and deep dermis without Wood's lamp accentuation. The mixed type has elements of both and appears as deep brown colour on Wood's lamp examination. There is accentuation of only the epidermal component.[67]

The treatment of melasma is difficult particularly in dark skinned patients. The challenge is to obtain decrease in melasma pigment without unacceptable hypopigmentation or post- inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Protection from sun is imperative with the use of broad spectrum sunscreen, seeking shade as much as possible and use of protective caps and clothing. An array of conventional treatments that have been found effective include topical depigmenting agents like hydroquinone, azelaic acid and kojic acid often in combination with other topical therapies such as tretinoin, topical corticosteroids and chemical peeling. Topical azelaic acid is an effective and well tolerated treatment for hyperpigmentation in dark skinned patients. Moreover, selective removal of pigment by lasers is becoming increasingly popular. The past experience with the use of conventional high-fluence Q-switched Nd: YAG laser (QSNYL) in melasma has shown it to be effective in removing the pigment though it may be associated with risk of post-inflammatory pigmentation in a few patients.[8] We report the efficacy and safety of 1064-nm Q-switched low-fluence (low pulse energy) Nd: YAG laser, topical 20% azelaic acid cream and the combination of both in patients of melasma in three study groups of 20 patients each. Outcome was assessed in relation to reduction of pigment and area of pigmentation using melasma area and severity index (MASI) score.[9]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sixty untreated Indian patients with age group 18 years and above of either sex from the out patients department diagnosed as melasma were included in the study. These patients were randomly divided into three groups (group A–20 patients of melasma treated with low-fluence QSNYL, group B–20 patients of melasma treated with 20% azelaic acid cream and group C–20 patients of melasma treated with combination of both). Patients on oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, pregnant and lactating women and patients with any systemic or endocrinological illness or hypersensitivity to the azelaic acid or topical anaesthetic cream were excluded from the study.

The diagnosis of melasma (epidermal, dermal or mixed) was made based upon clinical appearance, Wood's lamp examination and 2-mm skin punch biopsy in consenting patients. The protocol of the study was approved by the Institutional ethical committee. Informed written consent was obtained from all the patients before inclusion into the study. All the patients were advised sun protection and use of a sunscreen lotion (of SPF 15) during the study period. Photographs at the beginning (0 week), during (at 6 weeks) and at the end of treatment (at 12 weeks) were taken for documentation.

In group A, topical anaesthesia with eutectic mixture of lignocaine and prilocaine was applied for 2 h under occlusion prior to laser for patient comfort session. Treatment was performed with the hand piece held perpendicular to skin surface with minimum overlap. All personnel in the laser room wore appropriate eye protection glasses during the treatment. The patient wore a silicon-coated lead shield for eye pretection provided by the manufacturer of laser (Med-lite C6).

Low-fluence 1064-nm QSNYL (Med-lite C6, Hoya Con Bio Inc., Fremont, CA, USA) was administered at parameters 6-8 mm spot size (SS), 10 Hz, 0.5-1 J/cm2, 10 passes at weekly intervals for a total of 12 weeks. Increment of 0.1 J/week was done till energy fluence of 1 J/cm2 was attained and was continued at 1 J/cm2 till 12th week. Immediate lightening or erythema of skin was taken as the end point. In group B, patients were asked to apply topical azelaic acid 20% in cream base, twice daily, over the lesion for duration of 12 weeks. In group C, patients were given a combination of both, low-fluence 1064-nm Q-switched Nd: YAG laser once weekly as given in group A and topical azelaic acid 20% in cream base twice daily application over the lesion as in group B for a duration of 12 weeks except on the day of laser therapy in the morning.

All the recruited patients completed the study. Evaluation of results of the 60 patients was made at 6 and 12 weeks with Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI). P value of <0.05 was taken as significant and P ≤ 0.001 as highly significant. Patients were also observed for any side effects during the treatment.

Statistics

The statistical analysis was done using chi square test, paired and unpaired student t-tests.

RESULTS

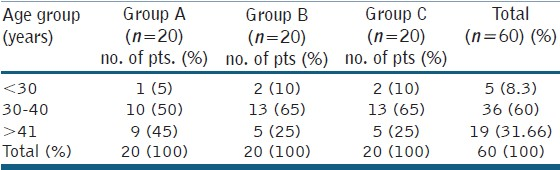

The study comprised of 59 females and 1 male. The mean age of the patients was 37.7 ± 6.63 years. The youngest patient was 28 years old and the eldest was 55 years old at the time of inclusion into the study. Majority of the patients were in the age group 30-40 years (36 patients). There were 5 patients in the age group < 30 years and 19 in the age group > 40 years of age [Table 1]. There were 31 (51.7%) patients with Fitzpatrick's type IV skin, followed by Fitzpatrick's type V skin seen in 28 (46.7%) patients and Fitzpatrick's type III skin in 1 (1.7%) patient. All the three groups were comparable with no statistically significant difference in the age distribution, skin phototype, duration of melasma and pattern of melasma. The duration of melasma ranged from 6 months to 30 years and the mean duration of melasma was 6.3 years. Onset of melasma during pregnancy was seen in 36.7% female patients. However, the maximum number of patients noted that the onset of melasma was not related to the pregnancy (46.7% female patients). Ninety percent of the patients noticed darkening of melasma in summer months. More than half of the patients had a positive family history of melasma (55%).

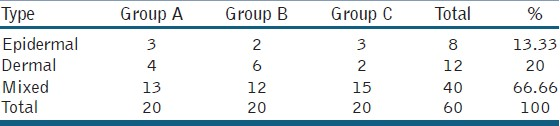

Centrofacial melasma was the most common type (88.33%), followed by malar type (11.7%) of melasma. None of the patients had mandibular pattern of melasma. On Wood's lamp examination, epidermal melasma was found in 8 (13.33%), dermal in 12 (20%) and mixed in 40 (66.66%) cases [Table 2]. Only five patients gave consent for the skin biopsy. The clinical and Wood's lamp examination matched with the histopathology findings in all five cases. Out of those five patients, three were of mixed melasma and rest two were of epidermal type of melasma.

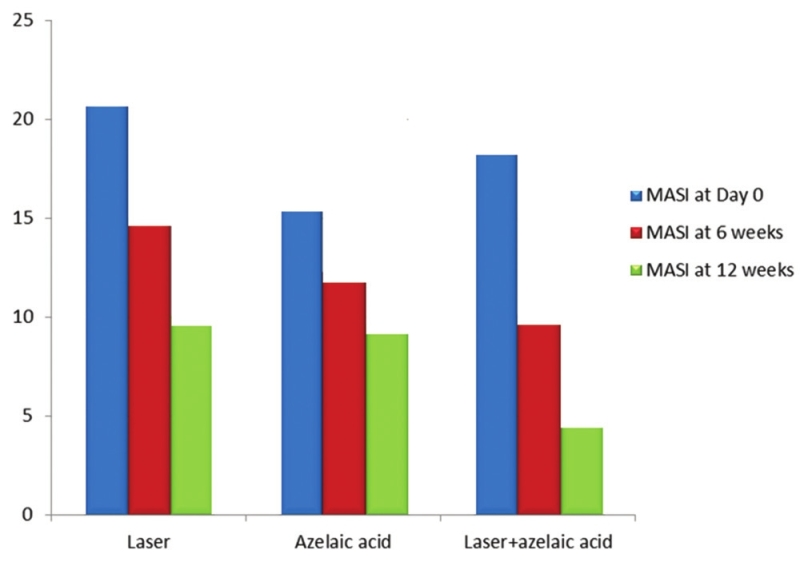

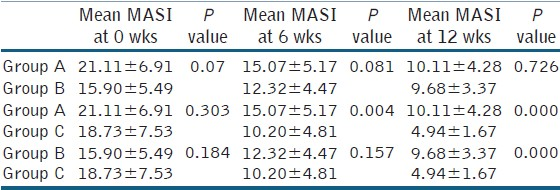

Group A had a mean baseline MASI score 21.11 ± 6.91, group B 15.90 ± 5.49 and group C 18.73 ± 7.53. These were comparable with no statistically significant difference between the groups (P > 0.05). After completion of treatment i.e., after 12 weeks, the mean MASI score in three groups was 10.11 ± 4.28 in group A, 9.68 ± 3.37 in group B and 4.94 ± 1.67 in group C [Figure 1]. All the three groups showed statistically significant improvement (P < 0.05) after treatment. The clinical improvement in groups A, B and C is shown in [Figures 2–4].

- Melasma area and severity index (MASI) at baseline, 6 weeks and 12 weeks in groups A, B and C. •Significant reduction of MASI scores (P < 0.001) at 6 weeks and 12 weeks in group A (QSNYL), group B (Azelaic acid) and group C (QSNYL and azelaic acid)

- A patient of melasma treated with Q-Switched Nd: YAG Laser at (a) week 0 (MASI 25.8), (b) week 6 (MASI 14.8) and (c) week 12 (MASI 10.8)

- A patient of melasma treated with 20% azelaic acid cream at (a) week 0 (MASI 20.7), (b) week 6 (MASI 17.9) and (c) week 12 (MASI 8.9)

- A patient of melasma treated with a combination of Q-Switched Nd: YAG Laser and 20% azelaic acid cream at (a) week 0 (MASI 10.6), (b) week 6 (MASI 5.2) and (c) week 12 (MASI 4.1)

The improvement in the MASI score after therapy was maximum in group C (combination of low-fluence laser and azelaic acid cream), followed by group A (low-fluence laser) and group B (20% azelaic acid cream). The improvement was statistically highly significant in group C as compared to group A (P < 0.001) and group B (P < 0.001). However, no statistically significant difference was observed in the reduction of MASI scores between group A and group B (P > 0.05) [Table 3].

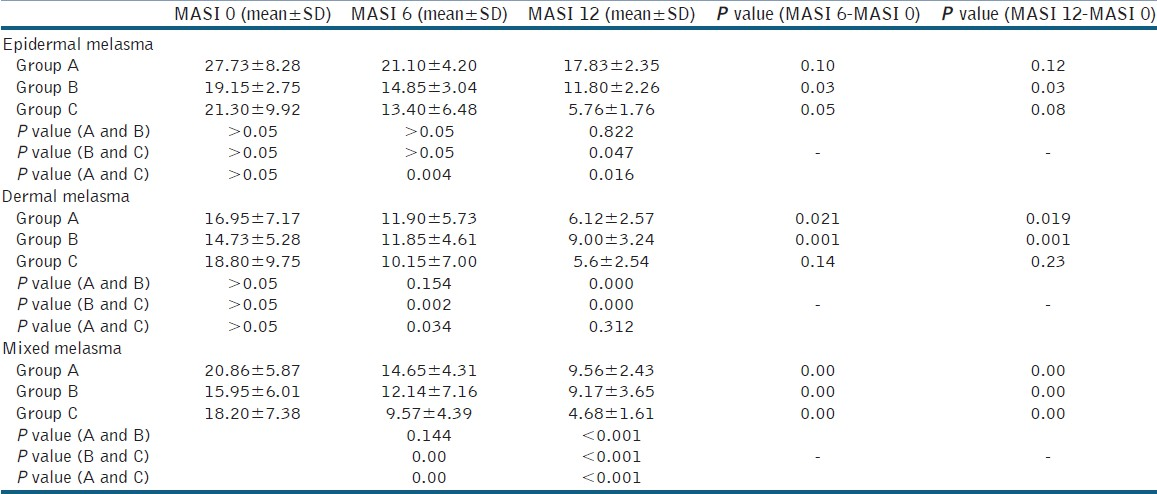

Significant reduction in mean MASI was observed after 12 weeks of treatment with all three modalities of treatment in epidermal, dermal and mixed melasma. However on comparing the three groups, in epidermal melasma, improvement was statistically significant in group C as compared to group A (P < 0.05) and group B (P < 0.05). Though, no statistically significant difference was observed in the reduction of MASI scores between group A and group B (P > 0.05). In dermal melasma, improvement was statistically significant in both groups A and C when compared to group B (P < 0.05). However, no statistically significant difference was observed in reduction of MASI scores between group A and group C (P > 0.05). In mixed melasma, improvement was statistically highly significant in group C as compared to group A (P < 0.001) and group B (P < 0.001) [Table 4].

The reduction in mean MASI was significant after 12 weeks of treatment with all the three modalities of treatment in both the skin types IV and V. The mean MASI reduction in patients with skin phototype IV was 51.8%, 37.6% and 71.4% in groups A, B and C respectively. Similarly, the mean MASI reduction in patients with skin phototype V was 47.4%, 37.7% and 69.6%, respectively. The difference in the reduction of mean MASI scores of the two groups (phototypes IV and V) was, however, not statistically significant. Only 1 patient belonged to skin phototype III (group C) and achieved 66.3% reduction in MASI score.

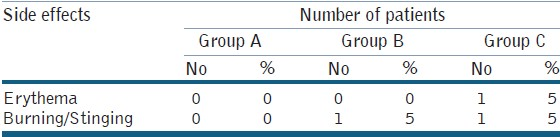

No complications were observed in patients who received low-fluence QSNYL. Only 1 (5%) patient treated with topical 20% azelaic acid cream experienced slight burning sensation. In combination group, 1 (5%) patient developed erythema and 1 (5%) suffered slight burning sensation. All these side effects subsided within 1 h in all of the patients. None of the patient suffered worsening of melasma on treatment [Table 5].

DISCUSSION

Melasma is a common disorder of hyperpigmentation in Asians. In the present study, the maximum number of patients belonged to the age group 30-40 years. The mean age of presentation in this study was 37.7 years. These findings are consistent with an earlier study in Caucasian patients which reported mean age of onset of melasma at 30 years.[10] The most common pattern of melasma was centrofacial (88.33%) followed by malar pattern (11.66%) and this corroborates with other Indian studies.[11] On Wood's lamp examination, epidermal melasma was present in 8 (13.33%), dermal in 12 (20%) and mixed in 40 (66.66%) cases. This is in contrast with the earlier studies which reported that the epidermal type is the most common (72%), followed by dermal (22%) and mixed type (5%) of melasma.[6] Our patients mostly belonged to photypes IV and V. The percentage reduction of mean MASI was higher in patients with phototype IV in all three groups. It correlates with the well-known fact that fairer skin respond better to therapy.

The treatment of melasma is difficult and is a challenge due to the non availability of a universally effective agent. Hydroquinone (HQ) (2-5%) is the most frequently prescribed depigmenting agent worldwide and has been the gold standard molecule in the treatment of melasma either alone or in combination with other agents for the past 50 years. Irritant or allergic contact dermatitis, paradoxical post-inflammatory hypermelanosis and confetti-like depigmentation are unacceptable effects with HQ use. This has led to an increased use of topical azelaic acid (20%) which is a competitive inhibitor of tyrosinase for the treatment of hyperpigmentation.

Azelaic acid causes inhibition of DNA synthesis and mitochondrial enzymes, thereby inducing direct cytotoxic effects on melanocytes. Moreover, it acts selectively on hyperactive and abnormal melanocytes, thus neither leukoderma nor exogenous oochronosis are associated with its use.[12] In the instant study, the improvement in melasma with twice daily application of azelaic acid 20% cream as measured by mean MASI was statistically significant both during and at the end of treatment. The average improvement noticed at 6 weeks and 12 weeks was 22.51% and 38.80%, respectively. Only 1 (5%) patient experienced slight burning sensation which lasted for less than an hour. The findings are supported by a 24-week study carried out by Lowe et al. who found that mean pigment intensity scores decreased significantly in the azelaic acid group (20.0% decrease) over the vehicle group (3.9% decrease).[13] Verallo-Rowell et al. in a 24-week study demonstrated that overall response was significantly higher in the azelaic acid group (78.3%) compared with the hydroquinone group (19.4%).[14] In azelaic acid group of the study vide supra, only 11 patients reported mild, transient, local irritant sensations and 5 patients experienced pronounced primary irritant reactions.

Lasers are the most recent addition to a dermatologist's armamentarium and their role in the management of pigmentary disorders is being explored for the last 3 decades. Q-switched Nd: YAG laser (QSNYL) is one of the pigment specific lasers. It emits energy in the near infra-red range at 1064 nm. It works on the principle of selective photothermolysis, and in doing so, limits the damage to the melanosomes.[15] The QSNYL (1064 nm) has been shown to cause dermal and epidermal melanosomes rupture in melanocyte and destruction of dermal melanophages.[16]

The exact mechanism by which low-fluence 1064-nm QSNYL improves melasma is unclear, however, it has been proposed that by delivering repetitive laser energy using a sub-photothermolytic fluence (<5 J/cm2) over a large spot size, melanin granules are fragmented and dispersed into the cytoplasm without cellular destruction. The selectivity of this light on a sub-cellular level, as it breaks apart pigments only and not cells, leads this modality to be dubbed as ‘sub cellular selective thermolysis’ (SSP).

Traditional, high fluence therapies for pigmented lesions have yielded good results even in resistant melasma in fair skinned patients. However, the same fluences have resulted in increased frequency of side effects in dark skinned patients. Thus, sub-thermolytic (low fluence) therapy is being considered as an option for treating skin pigmentation like melasma. However, there is a dearth of clinical data regarding the efficacy of low-fluence QSNYL in melasma especially in Indian patients.

In our study, results were statistically significant with 1064-nm low-fluence QSNYL after 6 weeks and 12 weeks. The average improvement of 28.61% at 6 weeks and 52.10% at 12 weeks in mean MASI score was obtained in laser group with no side effects. In a study by Polnikorn et al., two cases of long standing refractory dermal melasma responded to treatment with the Medlite C6 using once weekly treatment for 10 weeks with 1064-nm QSNYL at sub photothermolytic fluence (<5 J/cm2), resulting in reduction of epidermal and dermal pigment.[17] In 2009, Cho et al. demonstrated that use of 1064 nm QSNYL with low pulse energy in 25 patients at 2 weekly intervals (2.5 J/cm2, 6-mm spot size, two passes with appropriate overlapping) as an effective treatment for melasma.[13] In 2010, Suh et al. in their study using 1064 nm QSNYL at 1-week interval for 10 weeks showed that it is a safe and effective modality for treating melasma in Asian patients.[18] In a study by Kar et al., in which 25 patients were treated with subthermolytic Q-switched laser therapy for a duration of 12 weeks,[19] the average improvement achieved was 47.93% which is comparable to that achieved in our study with average improvement of 52.10% with minimal side effects.

In our study, in epidermal melasma, best results were obtained with the combination of low-fluence 1064-nm QSNYL and topical 20% azelaic acid cream. The lightening of pigment in epidermal melasma by combination therapy occurred probably due to the synergistic action of laser and azelaic acid. Thus, daily topical azelaic acid acted as a maintenance therapy with once weekly laser therapy session. On comparing the three groups in dermal melasma, the combination group and the laser group showed almost similar results and azelaic acid alone showed the least improvement in MASI score. We postulate that the lightening of pigment in dermal melasma by low fluence 1064 nm QSNYL occurred due to dermal and epidermal melanosome rupture and destruction of dermal melanophages. Topical azelaic acid has a limited penetration ability so as to act on the dermal component of melasma. Therefore, the results are almost similar in the combination therapy and laser alone while least improvement is achieved with topical azelaic acid alone. Also, in mixed melasma, best results were obtained with combination therapy followed by laser therapy alone and least with topical azelaic acid cream. Here again, the azelaic acid is acting synergistically with the laser in the combination group thereby giving the best results.

The average improvement noticed in mean MASI by using combination of low fluence QSNYL and 20% azelaic acid cream at 6 weeks and 12 weeks was 46.78% and 72.75%, respectively with minimal side effects. There is no study in the English literature to the best of our knowledge which evaluates the efficacy of the combination of low fluence QSNYL and 20% azelaic acid cream.

CONCLUSION

A combination of low fluence QSNYL with azelaic acid is a promising option for the treatment of melasma and needs to be further explored.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- Endocrinologic profile of patients with idiopathic melasma. J Invest Dermatol. 1983;81:543-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Light microscopic, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural alteration in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

- [Google Scholar]

- Melasma: A clinical, light microscopic, ultra structural, and immunofluorescence study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:698-710.

- [Google Scholar]

- Melasma: Histopathological characteristics in 56 Korean patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:228-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lasers in dermatology. In: Freedburg IM, Eisen AZ, Ketal W, eds. Fitzpatrick dermatology in general medicine (7th ed). New York: McGraw Hill; 2007. p. :2274.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for clinical trials in melasma: Pigmentation disorders academy. Br J Dermatol. 2006;156:21-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Topical tretinoin (retinoic acid) improves melasma. A vehicle controlled, clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:415-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Safety and efficacy of glycolic acid facial peel in Indian women with melasma. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:354-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Azelaic acid. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in acne and hyperpigmentary disorders. Drugs. 1991;41:780-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Azelaic acid 20% cream in the treatment of facial hyperpigmentation in darker-skinned patients. Clin Ther. 1998;20:945-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Double-blind comparison of azelaic acid and hydroquinone in the treatment of melasma. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1989;143:58-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Selective photothermolysis. Precise microsurgery by selective absorption of pulsed radiation. Science. 1983;220:524-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- A low fluence Q-switched Nd: YAG laser modifies the 3D structure of melanocyte and ultrastructure of melanosome by subcellular-selective photothermolysis. J Electron Microsc (Tokyo). 2011;60:11-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of refractory dermal melasma with the MedLite C6 Q-switched Nd: YAG laser: Two case reports. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2008;10:167-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Melasma treatment in Korean women using a 1064-nm Q-switched Nd: YAG laser with low pulse energy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e847-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study on efficacy of high and low fluence Q-switched Nd: YAG laser and glycolic acid peel in melasma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:165-71.

- [Google Scholar]