Translate this page into:

Adjuvant Narrow Band UVB Improves the Efficacy of Oral Azithromycin for the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Inflammatory Facial Acne Vulgaris

Address for correspondence: Dr. Amir Feily, Department of Dermatology, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Honari Clinic, Motahari Street, Jahrom, Iran. E-mail: dr.feily@yahoo.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Acne vulgaris (AV) is a common inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit. A variety of treatment modalities are available for the treatment of AV. Among the available options, oral azithromycin is popularly prescribed for its proven anti-inflammatory effects. Narrow band UVB (NBUVB) also has a potent anti-inflammatory action. Concomitant use of both modalities may result in a synergistic therapeutic response; however, the combined efficacy has not yet been evaluated for the treatment of inflammatory AV.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of oral azithromycin plus NBUVB (peak 311 nm) to oral azithromycin alone for the treatment of moderate to severe inflammatory AV.

Materials and Methods:

A randomized, open-label, clinical trial was conducted over 4 weeks. Subjects were randomized into two groups. Group 1 received 500 mg of oral azithromycin three times per week. Group 2 received 500 mg of oral azithromycin plus NBUVB three and two times per week, respectively. Concomitant topical or oral AV treatments were not permitted during the treatment period. Response to treatment was measured by photographic records at the primary endpoint (2 weeks) and at the end of treatment.

Results:

One hundred and four subjects were enrolled in the trial; 94 subjects completed the treatment period of the study. Group 2 demonstrated significant clinical improvement of the inflammatory papular lesions (88.55%) compared with group 1 (70.34%) at the end of treatment (P = 0.002). The clinical response of pustular (P = 0.562), nodular (P = 0.711) and cystic (P = 0.682) lesions did not significantly differ between the two treatment groups. Interestingly, response to treatment in group 2 had a significant anatomical predilection for the forehead (P = 0.023). There was no side-effect except erythema, which subsided within 1-2 days.

Conclusion:

NBUVB plus oral azithromycin is more effective than oral azithromycin alone for treating papular lesions of inflammatory AV. NBUVB is certainly a viable adjunct in acne therapy.

Keywords

Acne vulgaris

azithromycin

narrow band UVB

INTRODUCTION

Acne vulgaris (AV) is one of the most common dermatological diseases affecting an upwards of 80% of adolescents[1] and peaking in prevalence around the 17th year of life.[2] Areas of the face, neck, chest and back are typically affected,[3] with lesions being classified as either inflammatory or non-inflammatory[4] based on the degree of erythema. The pathogenesis of AV is mutifactorial and includes features of follicular hyperkeratosis, seborrhoea, bacterial colonization and inflammation.[5]

Propionibacterium acne (P. acne) is the most frequently isolated organism in AV.[6] Therefore, antibiotic therapy has long been used in the management of moderate-to-severe AV due to its positive effects in suppressing P. acne growth, reducing the production of inflammatory mediators and its immunomodulatory activity.[4] Several tetracyclines and macrolides are frequently prescribed.[7] Use of azithromycin, an azalide, has particular advantages[8] such as deep tissue penetration and a relatively long terminal half-life.[9] It is more stable than erythromycin in low gastric pH; it produces fewer gastrointestinal side-effects and lacks concerning drug-drug interactions.[8] Nonetheless, response to treatment generally takes at least 3 months and patients are frequently unsatisfied with the level of response.

Recently, laser and light-based therapies have been gaining popularity for the treatment of inflammatory AV. Specifically, UVB exerts antimicrobial activity by direct inhibition of proprionibacteria.[10] These optical devices mainly target P. acne by activating porphyrins produced by the bacterium.[5] P. acne naturally produces endogenous porphyrins that are composed of coproporphyrin III (CPIII) and protoporphyrin IX (PpIX).[11] PpIX is a photosensitizer and, once activated, accumulates in the epidermal cells and pilosebaceous units. PpIX then reacts with oxygen to produce singlet oxygen, resulting in bacterial death.[1] Narrow band UVB (NBUBV) phototherapy emits light from 311 to 313 nm[12] and has demonstrated the capacity to significantly inhibit propionibacteria with a minimum dose of 0.30 J/cm2 .[13]

UVB radiation also serves as a potent modulator of cell-mediated immune responses.[1214] UVB has been found to stimulate increased production of Th2-derived cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine.[1015] IL-10 is thought to down-regulate IL-1-alpha production and has been associated with inhibition of antigen presentation by Langerhans cells.[1015] UV light also leads to a decrease in macrophage production of inflammatory cytokines.[16] These immunomodulating effects, in addition to the previously described antimicrobial activity of UV light, may result in a favourable synergistic therapeutic response when used in combination therapy with azithromycin; however, the combined efficacy of these modalities has not yet been evaluated for the treatment of inflammatory AV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A single-centre, open-label, randomized, controlled, clinical trial was conducted over 4 weeks at the Imam Hospital in Ahvaz, Iran, between July 2010 and December 2011. The study received approval from the institutional review board of the Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences in July 2010, protocol approval number ETH-054. Subjects were recruited on a referral basis. Inclusion criterion included male or female subjects between the ages of 15 and 35 years with a diagnosis of moderate to severe inflammatory AV based on the presence of inflammatory papules, pustules, nodules or cysts for at least 1 week, as determined by dermatological examination and per protocol. Pregnancy, breastfeeding and use of topical or oral acne medication within the previous 4 weeks were exclusionary. Subjects with a prior history of a photosensitivity disorder or those who were using photosensitizing agents, were also excluded from the study.

One hundred and four patients of both sexes, skin types 3 and 4 with moderate to severe acne, were enrolled in this study. Subjects were randomly divided into two groups. The first group received 500 mg of oral azithromycin three times per week after meals. The second group received 500 mg of oral azithromycin alternatively two of three treatment days, 5 min of NBUVB therapy to the affected areas was performed. Concomitant topical or oral AV treatments were not permitted during the treatment period.

Response to treatment was measured by clinical assessment and photographic records at the primary endpoint (2 weeks) and at the end of treatment. Mild response was defined as <30% improvement; mild-moderate response was defined as 30-59% improvement; moderate response was defined as 60-79% improvement, and high response was defined as >80% improvement. For descriptive purposes, the face was divided into four anatomical zones: Zone 1 (forehead), zone 2 (central face), zone 3 (left face) and zone 4 (right face). Lesions were further characterized as papular, pustular, nodular or cystic. The total number of inflammatory lesions were counted and categorized by zone during each clinical assessment visit: Baseline (prior to treatment), Week 2 visit and Week 4 visit. Phototherapy was given by a manual NBUVB system (DERMAPAl, Daavlin; located in Bryan, Ohio) and the treatment area was 2.54 cm × 11.4 cm with narrow band power output of 3.9 MJ/s/cm2 approx. In our pilot study on skin types 3 and 4, we found that almost 5 min use of this instrument by the above output is our minimal erythema dosage (MED). Our MED was 1170 MJ/cm2 .

For phototherapy, we divided the face to four anatomical zones: Zone 1 (forehead), zone 2 (central face), zone 3 (left face) and zone 4 (right face). For each patient we located the instrument 5 min above each anatomical zone. In total 20 min for every patient.

All subjects were asked to complete IRB-approved patient satisfaction surveys. The survey was based on the subjects’ subjective response to treatment and scored as: I am not satisfied (score 1), I am partially satisfied (score 2), I am satisfied (score 3) and I am very satisfied (score 4). A score of 1 represented the least subject satisfaction, while a score of 4 represented complete satisfaction.

Data were gathered and entered in an Excel spreadsheet by a single individual. Subject names and date of birth were then independently checked to prevent duplicate entries. Data entry was verified prior to data analysis. There was no missing data prior to analysis. Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS version 17. Significance levels of P ≤ 0.05 were used for all testing.

RESULTS

One hundred and four subjects were enrolled in the trial and 94 subjects completed the treatment period of the study. Gender distribution was 82 (78.8%) female and 22 (21.2%) male. Age distribution ranged from 15 to 35 years. Fifty-two subjects were randomized into group 1 and received 500 mg of oral azithromycin three times per week for a total of 4 weeks. Fifty-two subjects received 500 mg of oral azithromycin plus NBUVB, as described in the methods section, for a total of 4 weeks. A total of 10 subjects withdrew from the study after receiving at least one treatment dose. Seven subjects withdrew from group 1 for personal reasons. Three subjects withdrew from group 2; two subjects withdrew participation for personal reasons, while one was withdrawn secondary to an adverse event (increased photosensitivity with NBUVB treatment).

There were no side-effects except erythema, which subsided within 1-2 days. In the first few sittings, we had erythema in some patients, but it did not last long. This may be because we did not increase the dosage of phototherapy during the study, and it was performed by constant dosage.

In general, group 2 demonstrated increased clinical improvement of all lesion types in all facial zones when compared with group 1 (67.32% of lesions vs. 62.50%), but this difference was not statistically significant. However, group 2 did demonstrate significant clinical improvement of inflammatory papular lesions (88.55%) compared with group 1 (70.34%) at the end of treatment (P = 0.002) [Table 1]. Clinical response of pustular (P = 0.562), nodular (P = 0.711) and cystic (P = 0.682) lesions did not significantly differ between the two treatment groups.

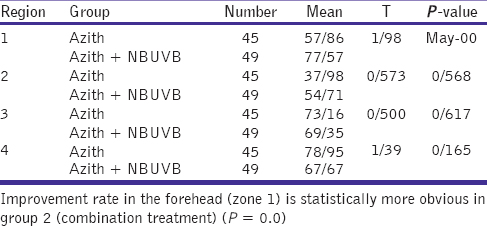

We compared the improvement rate of lesions within facial zones 1-4. Notably, there was a significant difference in improvement between the two groups for lesions on the forehead (zone1); the response rate for group 2 was 77.57% compared with 57.86% improvement in group 1 (P = 0.023) [Table 2]. Furthermore, subject satisfaction with treatment, determined as described in the methods section, was significantly greater for group 2 (P = 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Herein, we present first-time data supporting the improved efficacy of oral azithromycin plus NBUVB compared with oral azithromycin alone for the treatment of inflammatory AV. Combination therapy demonstrated a significant improvement of inflammatory papular lesions over use of oral azithromycin as a single-agent therapy (P = 0.002). However, it is important to note that this difference was not seen in more advanced AV lesions, such as pustules, nodules and cysts. Interestingly, response to combination therapy had a significant anatomical predilection for the forehead (P = 0.023).

Various systemic therapies are presently available for the management of inflammatory AV.[17] As stated previously, azithromycin has been accepted as one of the most safe and effective antibiotics used for this disease process;[18] however, response to treatment is variable and typically takes months of treatment to see clinical results. Phototherapy is currently used in dermatological practice to treat and manage several dermatoses.[19] There are several reports on the efficacy of many types of phototherapy and laser devices in the treatment of acne, including the potassium titanyl phosphate laser, the 1450-nm diode laser, the 585- and 595-nm pulsed dye lasers, low-intensity light treatment radiofrequency devices, intense pulsed light sources and photodynamic therapy using 5-aminolevulinic acid and indocyanine green.[20] Sigurdsson et al. demonstrated moderate improvement of acne to visible light that was thought to result from photodynamic destruction of P. acne.[15] In a separate report by Fluhr and Gloor, propionibacteria were significantly inhibited with a minimum dose of 0.30 J/cm2 of NBUVB and up to a maximum dose of 2.8 powers of 10 at 3.00 J/cm2 .[13] NBUVB phototherapy is a newer treatment modality that provides potential advantages to conventional UVB-based phototherapy. Although NBUVB is increasingly being used for the treatment of many dermatoses,[212223] to the best of our knowledge, its efficacy in the treatment of inflammatory AV has not been evaluated prior to our study.

We recognize the limitations of this study. All subjects were of the same ethnicity and were evaluated in a single institution. Other studies are necessary to evaluate whether the above findings are comparable to response rates in other ethnicities. Our study did not evaluate subjects in the paediatric population below the age of 15 years. However, prior studies have documented the safety of NBUVB treatment in children;[24] therefore, we feel that combination therapy may also be used in children under the age of 15 years with moderate to severe inflammatory AV. Lastly, each subject was only followed for 1 month after completion of the trial. Therefore, long-term follow-up data are unavailable to evaluate the stability of treatment and recurrence rates.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- Topical ALA-photodynamic therapy for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:183-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Azithromycin: A new therapeutical strategy for acne in adolescents. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clindamycin lotion alone versus combination lotion of clindamycin phosphate plus tretinoin versus combination lotion of clindamycin phosphate plus salicylic acid in the topical treatment of mild to moderate acne vulgaris: A randomized control trial. Indian J Dermatol VenereolLeprol. 2009;75:279-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of bacteria in acne vulgaris: A new approach. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1978;3:253-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global Allianceto Improve Outcomesin Acne. New insights into the management of acne: An update from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(Suppl):S1-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- The macrolides: Erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:613-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative study of the bactericidal effects of 5-aminolevulinic acid with blue and red light on Propionibacterium acnes. J Dermatol. 2011;38:661-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Narrowband UV-B phototherapy for the treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:537-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of oral azithromycin pulse with daily doxycycline in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol VenereolLeprol. 2003;69:274-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Suberythemogenic narrow-band UVB is markedly more effective than conventional UVB in treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:893-900.

- [Google Scholar]

- The antimicrobial effect of narrow-band UVB (313 nm) and UVA1 (345-440 nm) radiation in vitro. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1997;13:197-201.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-inflammatory properties of narrow-band blue light. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:605-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changes of comedonal cytokines and sebum secretion after UV irradiation in acne patients. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:139-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Dermatology Work Group. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 6. Guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Case-based presentations and evidence-based conclusions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:137-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Superior efficacy of azithromycin and levamisole vs. azithromycin in the treatment of inflammatory acne vulgaris: An investigator blind randomized clinical trial on 169 patients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;51:490-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Azithromycin versus tetracycline in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17:217-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- The mechanisms of action of phototherapy in the treatment of the most common dermatoses. Coll Antropol. 2011;35(Suppl 2):147-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative evaluation of NBUVB phototherapy and PUVA photochemotherapy in chronic plaque psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:533-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of the clinical efficacy of NBUVB and NBUVB with benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin in progressive macular hypomelanosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1318-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical study of repigmentation patterns with either narrow-band ultraviolet B (NBUVB) or 308 nm excimer laser treatment in Korean vitiligo patients. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:317-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of narrow-band UVB phototherapy in 150 patients with vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:162-6.

- [Google Scholar]