Translate this page into:

Role of Phenytoin in Diabetic Foot Ulcers

Address for correspondence: Dr. Ravi Kumar Chittoria, Department of Plastic Surgery, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry, India. E-mail: drchittoria@yahoo.com

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Of the complications of diabetes mellitus, foot ulcers are the most dreaded complications, as they can progress at an alarming rate and can be very difficult to treat. Various modalities have been described in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. One such modality of phenytoin therapy uses the disadvantage of the drug, that is, gingival hyperplasia to the advantage of wound healing. We hereby report a case of diabetic foot ulcer managed with injection phenytoin sprayed topically over the wound.

Keywords

Diabetes

foot ulcer

phenytoin

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder characterized by multiple long-term complications that affect almost every system in the body. Foot ulcers are one of the main complications of diabetes mellitus. Foot ulcers are common and estimated to affect 15% of all individuals with diabetes during their lifetime.[1] Its chronicity contributes to pain, suffering, disability, and diabetic foot osteomyelitis and is one of the leading causes of limb amputation.[23] Diabetic foot ulcer healing depends on many factors. It heals very slowly with primary closure of ulcer being almost impossible. Many agents are in use and are being tried for the promotion of wound healing to achieve the desired outcome, that is, formation of healthy granulation tissue. One such agent is phenytoin.

Phenytoin was first used in the year 1937 as a treatment for grand mal seizures,[45] and one common side effect of phenytoin observed was gingival hyperplasia.[6] Some studies carried out on the mechanism of this side effect have suggested the positive role of phenytoin, that is, fibroblast and cell proliferation and deposition of extracellular matrix, probably collagen deposition. The beneficial effect of phenytoin has been shown in promoting healing of decubitus ulcers,[78] venous stasis ulcers,[9] traumatic ulcers,[1011] burns,[12] and leprosy trophic ulcers.[13]

CASE REPORT

Our patient was a 34-year-old gentleman with a history of a wound in the right leg for 2 weeks following trivial trauma. He was a diagnosed with type 2 diabetes for 4 months, for which he was treated with irregular oral hypoglycemic agent. He had no other comorbidities.

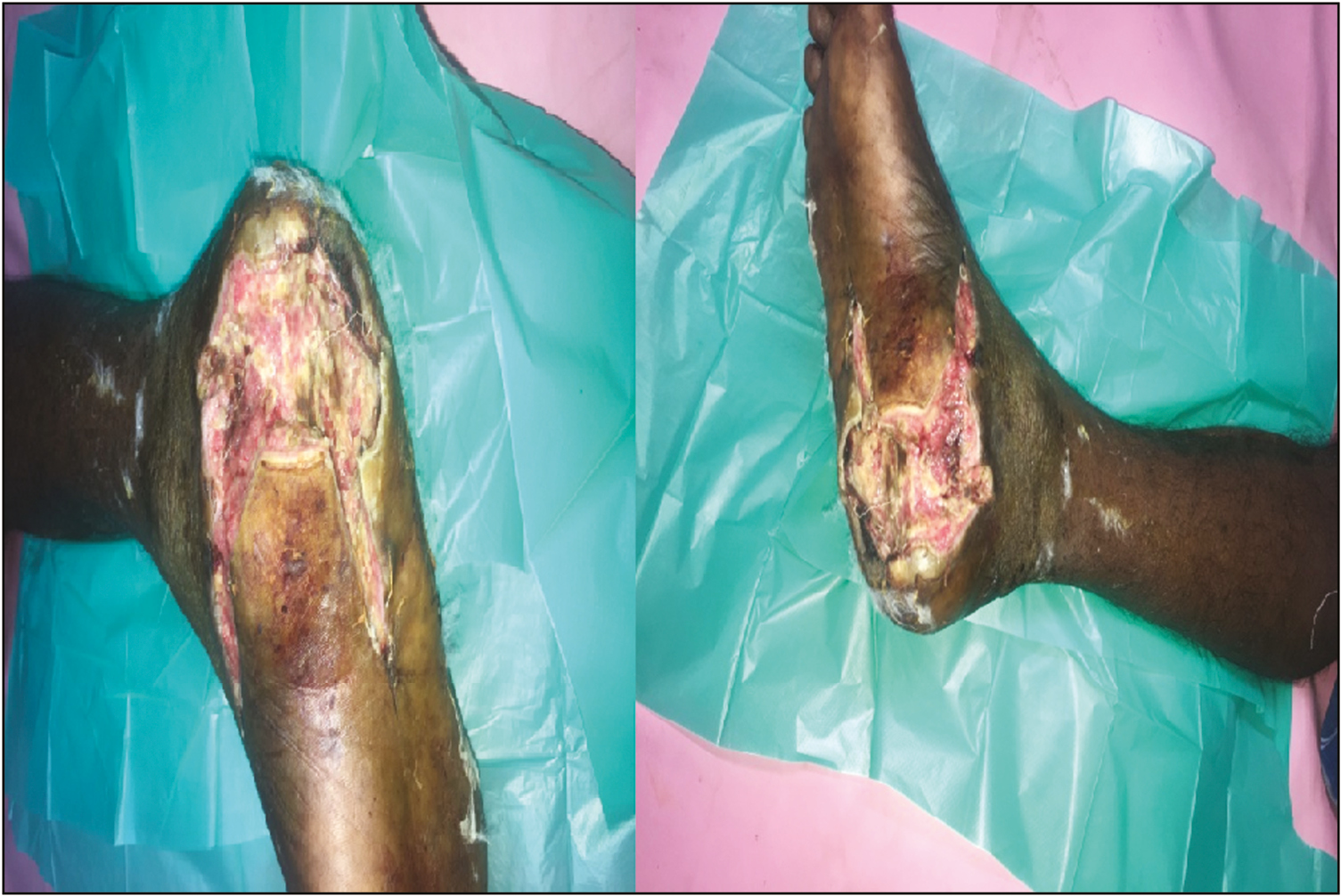

On presentation, he had a wound of size 10 × 6 cm in the heel of the right foot extending to the dorsum approximately 2 cm below the medial malleolus [Figure 1]. Calcaneum was exposed and periosteum was intact and slough was present. The wound base was filled with pale pink granulation tissue. There was another ulcer at the level of lateral malleolus, the bone was not exposed and was filled with pale pink granulation tissue.

- Wound at initial presentation

Evaluation showed that the patient had uncontrolled diabetes, which was managed with the help of an endocrinologist, and he was started on insulin. On X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging of the foot, there was no evidence of osteomyelitis. Wound tissue culture–specific antibiotics were started. Anemia was corrected with blood transfusions. Other workup for diabetes was also carried out. Assessment of wound was performed by Bates–Jenson wound scoring system.

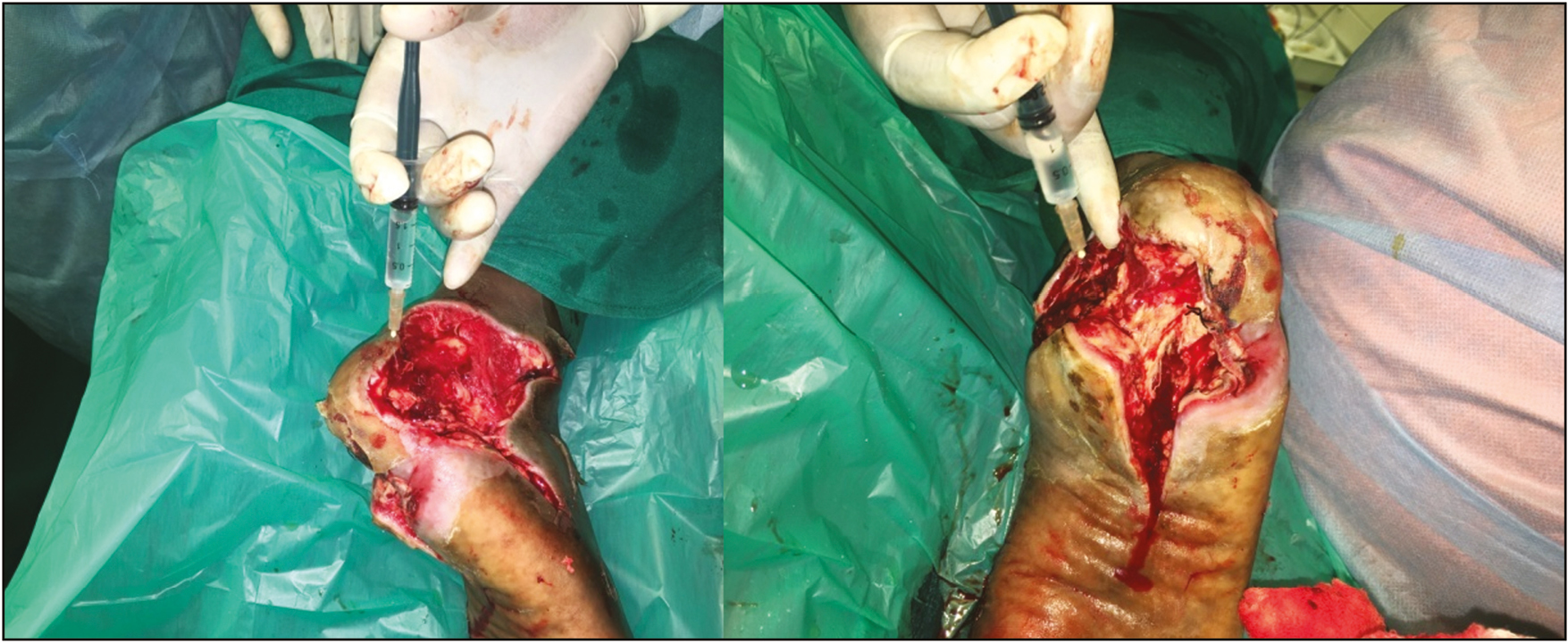

After serial debridement, injection phenytoin was sprayed on top of the wound and secondary dressing was carried out [Figure 2]. Injection phenytoin (50 mg/mL) solution was diluted using normal saline (0.9% NaCl) to prepare a phenytoin solution (5 mg/mL). This dressing was changed once in 3 days, and the phenytoin instillation was repeated at the time of dressing change. Serum phenytoin concentration was monitored regularly in the Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry, India, and it was always below 0.4 µg/mL, indicating only minimal absorption of phenytoin systemically. The patient did not have any pain while instillation. After five dressings, his wound had drastically improved, with the wound bed granulating well with pink healthy granulation tissue [Figure 3]. Bone had been covered with granulation tissue and the wound bed was now ready for cover.

- Wound after debridement and injection phenytoin being sprayed over the wound

- Wound after five applications of topical phenytoin

DISCUSSION

In 1938, Meritt and Putnam[4] published their noteworthy data using phenytoin to treat major, absence, and psychic equivalent seizures. In 1939, Kimball and Horan observed for the first time that gingival hyperplasia occurred in some patients who were treated with phenytoin. The earliest clinical trial, which was conducted in 1958, suggested that the patients with surgical wounds who were pretreated with oral phenytoin had less inflammation, less pain, and accelerated healing when compared with the controls.

Topical phenytoin sodium has wound-healing-promoting effects attributed to the following mechanisms: increased fibroblast proliferation, inhibition of collagenase activity, promotion of collagen disposition, enhanced granulation tissue formation, decreased bacterial contamination, reduced wound exudate formation, and upregulation of growth factor receptors.[14]

In 1991, Muthukumarasamy et al.,[15] in their study on the effect of topical phenytoin in diabetic foot ulcers, a prospective controlled clinical trial, had used phenytoin powder on the ulcer base. They came to the conclusion that the use of phenytoin to promote healing of diabetic ulcers is both effective and safe.

DaCosta et al.,[16] in their study, concluded that phenytoin alters the natural course of wound healing and may be of benefit in clinical situations where defective wound collagen deposition may lead to poor wound healing and consequent morbidity and mortality. It was noted that there is fibroblast proliferation and neovascularization in the wounds treated with phenytoin compared with controls at 3 days. By day 6, the inflammatory infiltrate had almost totally subsided in the treated wounds, but fibroblast infiltration and angiogenesis were still persistently marked.[1617]

Shaw et al.[17] concluded that there were no differences in diabetic foot ulcer closure rates or in diabetic foot ulcer area over time between the two groups when phenytoin is used.

Tauro et al.[18] observed 200 patients with diabetic ulcers. One hundred patients underwent topical phenytoin dressing, whereas the remaining managed with conventional wound dressing. They concluded that topical phenytoin aids in faster healing of diabetic wounds with better graft take-up.

All the studies that are mentioned stated that phenytoin causes increased fibroblast proliferation, enhances granulation tissue formation, and decreases bacterial contamination. However, Shaw et al.[17] stated that there were no differences in diabetic foot ulcer closure rates or in diabetic foot ulcer area over time between the two groups when phenytoin is used.

In our case, we noticed a significant improvement of wound based on the Bates–Jensen wound scoring system. This system is an objective standardized method of assessing and documenting wounds, which uses 13 different points in wound characteristics to give a wound score. This helps in initial assessment and documentation of the progress of the wound.[19]

CONCLUSION

Though diabetic foot ulcer can cause significant morbidity to the patient, if correctly managed, it can be treated effectively. Given the evident effectiveness of phenytoin in the promotion of wound healing as well as its availability, low cost, ease of use, and safety, we strongly recommend its use as a treatment for diabetic ulcers. A prospective study with more number of subjects is required to validate the same.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Peripheral vascular disease and diabetes. In: Harris MI, Hamman RF, eds. Diabetes in America. NIH Pub. No. 85–1468. Vol 16. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1985. p. :21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Osteomyelitis of the foot and ankle: diagnosis, epidemiology, and treatment. Foot Ankle Clin. 2014;19:569-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diabetic foot osteomyelitis: a progress report on diagnosis and a systematic review of treatment. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24:S145-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sodium diphenyl hydantoinate in the treatment of convulsive disorders. JAMA. 1938;111:1068-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous and immunologic reactions to phenytoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:721-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- ASHP drug information 2001. Vol 3. American Society of Health System Pharmacists; 2001. p. :78-79.

- Preliminary experience with topical phenytoin in wound healing in a war zone. Mil Med. 1989;154:178-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Topical phenytoin treatment of stage II decubitus ulcers in the elderly. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:675-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of sodium diphenylhydantoin in treatment of leg ulcers. N Y State J Med. 1965;65:886-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of phenytoin in healing of war and non-war wounds. A pilot study of 25 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:347-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- New application of an old drug: topical phenytoin for burns. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1991;12:96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of topical phenytoin with normal saline in the treatment of chronic trophic ulcers in leprosy. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:210-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study of topical phenytoin sodium in diabetic foot ulcer healing. Ann Int Med Den Res. 2017;3:SG43-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diphenylhydantoin sodium promotes early and marked angiogenesis and results in increased collagen deposition and tensile strength in healing wounds. Surgery. 1998;123:287-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- The clinical effect of topical phenytoin on wound healing: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:997-1004.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study of efficacy of topical phenytoin vs conventional wound care in diabetic ulcers. Int J Molecul Med Sci. 2013;3

- [Google Scholar]

- Bates–Jensen wound assessment tool: pictorial guide validation project. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2010;37:253-9.

- [Google Scholar]