Translate this page into:

Medial Thigh Contouring After Massive Weight Loss: The Liposuction-Assisted Medial Thigh Lift (LAMeT)

Address for correspondence: Dr. Verdiana Di Pietro, Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the University of Rome “La Sapienza”, Via Aldo Moro, 7, 67100 L’Aquila (AQ), Italy. E-mail: verdiana.di.pietro@gmail.com

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Introduction:

Following massive weight loss (MWL), medial contouring of the thigh is frequently requested to improve the appearance and function. Thigh lifting can be associated with significant complications if the medial thigh excess is removed en bloc. In this article, we describe the Liposuction-Assisted Medial Thigh Lift (LAMeT) and evaluate the outcomes and complications in a retrospective cohort study.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 54 females aged between 25 and 61 years with Grade 2 or 3 of thigh deformity on Pittsburgh Rating Scale (PRS) underwent medial thigh reduction. Vertical thigh lift with fascia suspension was performed in 25 patients with third degree of ptosis on PRS, horizontal thigh lift with fascia suspension was performed in 3 patients with second degree on PRS, LAMeT was performed in 26 patients with second and third degree on PRS.

Results:

Complications were observed in 35.7% of the patients that underwent the standard technique and in 3.8% patients that underwent the LAMeT. The most frequent complication was seroma. Hospital stay was significantly lower in the LAMeT group.

Conclusions:

Medial thigh lift is a safe and satisfying procedure because it provides aesthetic improvement in massive weight loss patients. The complication rate is higher when skin excess and laxity are removed en bloc because the resection of the excess tissue is poorly selective. The LAMeT preserves lymphatic and blood vessels and allows a more anatomical resection of the excess skin. Thus, the incidence of postoperative complications is lower and the patients heal faster.

Keywords

Body contouring

liposuction

massive weight loss

thigh lift

INTRODUCTION

With the growing popularity of bariatric surgery, the number of massive weight loss people has increased. If remarkable weight loss occurs, the skin laxity remaining at the level of arms, abdomen, hips and thighs can be significant enough to cause functional impairment, recurrent skin infections, as well as considerable psychological discomfort. Therefore, more people need plastic surgery to restore the shape and the harmony of the body.

From a surgical point of view, the inner thigh is a problematic body region for various reasons:

it is a humid body area so wounds tend to heal more slowly;

the skin is thin and weak so wound complications are likely to happen;

the closeness of the anus and of the external genitals increases the risk of infection of the wound;

the lymphatic vessels are very superficial and there is a high risk of lymphedema if they are damaged;

the superficial venous system can be easily damaged during the resection causing lower limb chronic edema;

the scars often tend to enlarge due to the high tension of the sutures;

scar retraction in the inguinal fold can cause labia majora and vagina deformation.

The medial thigh lift was described for the first time in 1957 by Lewis, however, the procedure did not succeed due to postoperative complications such as migration and enlargement of the scars, deformation of the vulva, and relapse of ptosis.[1] About 20 years after Pitanguy[2] proposed to anchor the anterior thigh flap to the pubis or to the muscle fascia to prevent the recurrence of the ptosis, in 1988, Lockwood[3] suspended the dermis of the skin flap to the Colles fascia to prevent complications such as dehiscence of the wounds, scar enlargement and migration, and ptosis recurrence. Since then other techniques were introduced[45678] in an attempt to correct the skin laxity, reduce the postoperative complications, and have good aesthetic results. In 2004, Le Louarn and Pascal[9] described their own technique of medial thigh lift: they used a horizontal scar located along the inguinal fold that never descend into the gluteal crease, reduced thigh volume with liposuction, and removed the cutaneous excess with surgical resection. This technique introduced important innovations: liposuction was performed on the entire thigh but aggressively under the area of resection to remove all the fat between the skin and the fascia; there was no dissection of tissues that were mobilized exclusively by liposuction; the direction of skin tightening was concentric in order to reduce the length of the incision and distribute the tension throughout the horizontal scar; lastly, the positioning of anchoring sutures to the Colles fascia reduced the tension on the suture and the probability of scar complications.

Despite its wide use and the evolution of the techniques, the medial thigh lift still remains a procedure full of pitfalls especially in massive weight loss population that present further problems such as very thin and poor quality skin, excess skin extended to the knee or below, nutritional and vitamin deficiencies due to the bariatric intervention that predispose to a slow and abnormal wound healing and bad quality scars. Sisti et al.[10] in a recent review report a complication rate of 42.72%, among which the most frequent were the wound dehiscence (18.34%) and the seroma (8.05%).

In the last 2 years the authors have evolved their technique of medial thigh lift in massive weight loss population: in fact while at beginning they used Lockwood’s classic technique with horizontal or vertical scar and Colles fascia suspension, today instead they use a vertical scar, no anchor suture, and concomitant liposuction (LAMeT): in this technique, because the resection is predominantly vertical and the tension of the suture is spread over the whole medial scar, stress on the inguinal scar is minimal and there is no need of Colles fascia suspension. Furthermore, liposuction lightens thigh flap of the thighs, mobilizes the tissues without need of undermining, and preserves vascular and lymphatic network of the medial region of the thighs. In this article, we report the encouraging results of LAMeT by evaluating the morbidity, complication rate, and final aesthetic result in comparison with the standard technique.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Between January 2011 and September 2017, a total of 54 massive weight loss (MWL) females aged between 25 and 61 years underwent medial thigh reduction: vertical thigh lift with fascia suspension was performed in 25 patients with third degree of ptosis on Pittsburgh Rating Scale (PRS), horizontal thigh lift with fascia suspension was performed in 3 patients with second degree on PRS, LAMeT was performed in 26 patients with second and third degree on PRS.

MWL patients were defined as those who have lost at least 50 pounds of weight and maintained a stable weight for more than 3 months. Fourteen patients had comorbidities (3 patients in the LAMeT group, 11 patients in the resection-only group), while 16 patients were smokers (6 patients in the LAMeT group, 11 patients in the resection-only group).

Markings

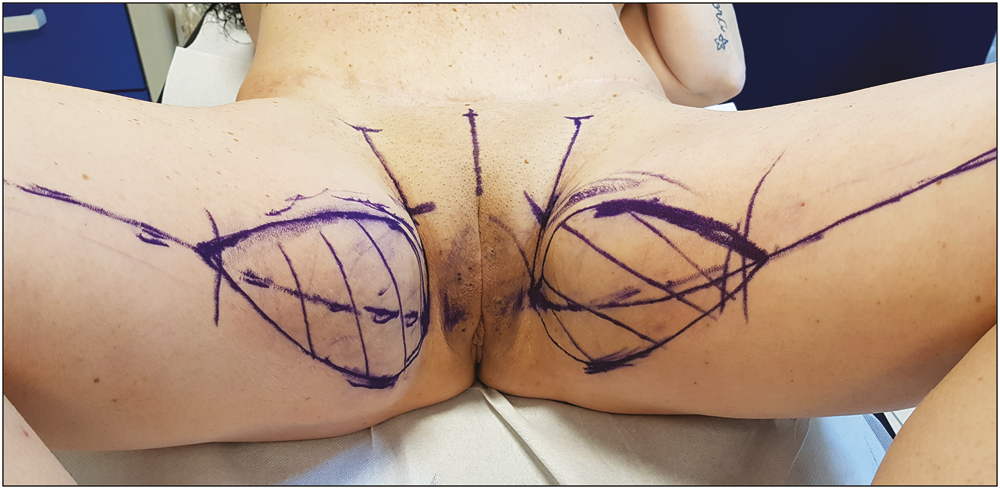

The patient is marked on the day of the surgery while standing in front of the surgeon with abducted legs. In patients with second degree ptosis, we use only the horizontal scar. The upper incision line is placed at the level of the inguinal fold approximately 1 cm caudally to avoid any distortion of the labia majora. The lateral apex of the ellipse reaches about half of the thigh while the medial one goes up to the gluteal fold, without ever crossing it. The ellipse thickness is calculated by pinch test. In case of significant ptosis (third degree), we also add a vertical scar. The line corresponding to the final scar is marked: the proximal point of this line is about 1 cm inside the adductor cord; the distal point is instead placed along the medial surface of the leg and corresponds to the end of the skin fold. The two points are joined to identify the ideal position of the scar so that it will be well hidden inside the thighs. While the patient is lying down, a horizontal line is drawn along the inguinal fold and up to the adductor cord taking care to draw the line 1 cm out of the fold to prevent the scar from causing a distortion of the labia majora.

The back line of the resection ellipse is drawn by firmly pulling the excess of the skin forward and tracing a straight line from the upper to the lower point. The anterior line is then drawn by firmly pulling the excess skin backward and tracing a straight line from the upper to the lower point. After that we mark a point placed at 7 cm from the vulva and other two points placed 7 cm laterally to the previous one. We join these points to the respective adductor cord. Sometimes we draw the line in a more oblique direction to avoid too much vertical scars on the pubis. The extent of horizontal resection is not calculated preoperatively but depends on the excess skin produced at the inguinal area by the vertical resection. The final appearance of the drawings is shown in Figure 1.

- LAMeT preoperative markings

Surgical technique

The operation is performed under general anesthesia and oro-tracheal intubation. The patient is in a supine position. Leg supports are not used so the limbs can be mobilized during surgery. We perform antibiotic prophylaxis with 2 g of cefazolin, 30–60 min before the surgical incision and after 3h in case of prolonged intervention. In case of allergy, the choice falls on clindamycin with a dosage of 600 mg. The patient also wears compression socks for all the duration of the operation as prevention of deep vein thrombosis. We take great care to ensure that the patient’s body temperature remains adequate throughout the surgery avoiding a too low temperature in the operating room, covering the patient with blankets, using a heated bed and heating the infusion fluids.

Standard technique according to Lockwood

The procedure begins with the incision of the proximal line; then a superficial dissection is performed to preserve the subcutaneous lymphatic network in the femoral triangle. After the resection of the horizontal ellipse and, when present, of the vertical one, the dermo-adipose flap of the thigh is anchored with permanent sutures to the Colles fascia to reduce the tension on the scar and obtain longer lasting results over time. Drains are placed before the suture. The procedure is then completed with suturing of the subcutaneous tissue, sub-dermal tissue, and skin with 2-0 and 4-0 resorbable threads.

Liposuction-assisted medial thigh lift (LAMeT)

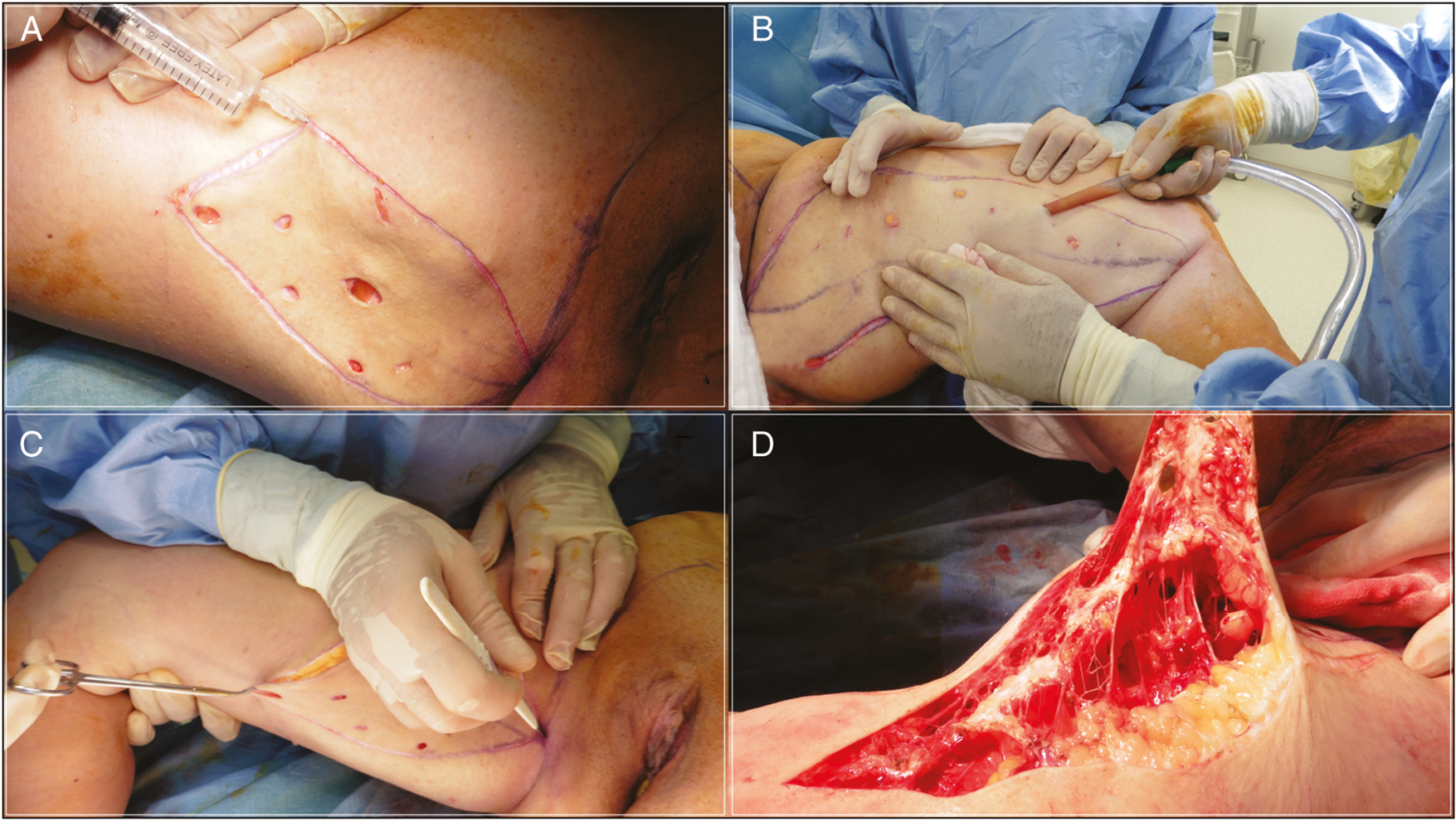

We begin the intervention with the infiltration of the liposuction areas [Figure 2A]: the solution is composed of 1 mg of epinephrine/L of 0.9% saline solution. The infiltration-liposuction volume rate is 1 to 1.

- LAMeT surgical technique step by step. (A) Liposuction area injection. (B) Liposuction of the ellipse of resection: all the subcutaneous fat has been removed. (C) Skin incision. (D) Subdermal resection of the excess skin to preserve the underneath connective network

We then infiltrate the incision lines with a solution consisting of 1.6 mg epinephrine/L of 0.9% saline solution: we use the needles for spinal anesthesia, which, being longer, allow us to be more rapid in infiltration.

After about 15–20 min from the infiltration, we perform the liposuction beneath the resection area. Using 4, 5, 6 mm diameter 3-hole cannulas we completely remove the fat between the skin and the muscle fascia going about 1 cm beyond the incision lines to facilitate the closure [Figure 2B]. At the end of liposuction, the skin must be 2 or 3 mm thick. If necessary, we perform a “standard” liposuction (final thickness of the skin of 1–1.5 cm) in the other parts of the thigh.

After the liposuction, we check if the drawings and the degree of tension of the suture are correct by putting temporary silk stitches. Liposuction tends to mobilize more tissue, so it may be necessary to enlarge the ellipse. In this case, we modify the anterior line because the skin of the anterior thigh is looser and because we want to prevent the scar from moving anteriorly becoming more visible. When we are satisfied with the drawings we incise the ellipse: the incision is bloodless, thanks to the previous infiltration [Figure 2C]. The ellipse is then removed at a very superficial level, just below the dermal layer [Figure 2D]; it is important to pay attention to the inclination of the coagulator that must be oriented towards the skin to avoid cutting too deeply. Once the ellipse has been removed, we put some staples or external silk stitches to make the definitive closure easier. At the level of the upper third it is important during the closure to lift the anterior flap about 2 cm upwards to better stretch the front thigh skin. This movement of the flap creates an excess skin in the inguinal fold: we mark the limits of the horizontal resection, orienting them along the line drawn at the pubic level during the preoperative markings. After infiltration and liposuction, we remove the excess skin always maintaining a very superficial dissection plane, immediately below the skin layer.

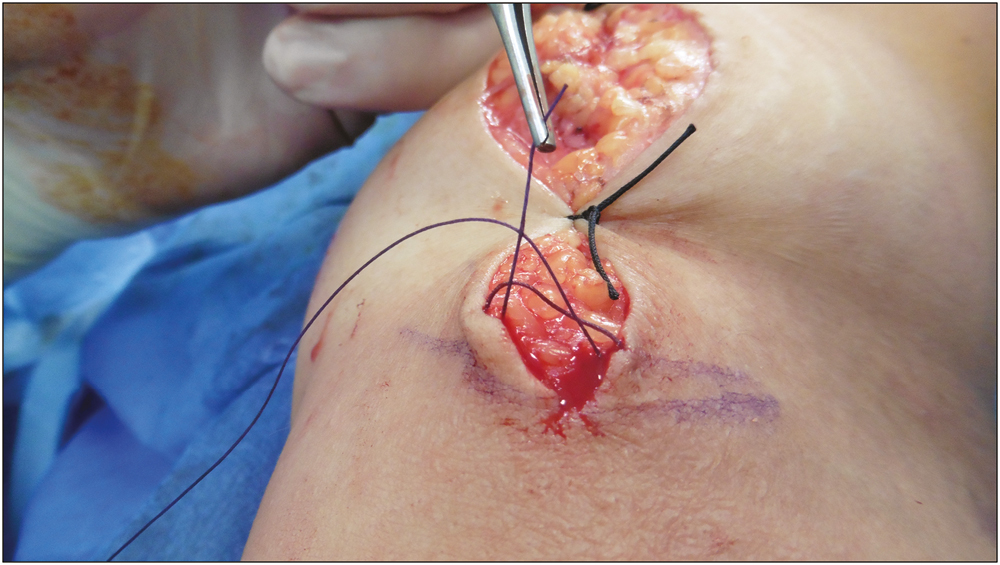

As evidenced by the description of the technique, the tissues are not undermined but mobilized by liposuction. The absence of dead spaces as well as the integrity of the lymphatic and vascular network thanks to liposuction, allow us to not use drains. We complete the surgery with the suture of the ellipse: we use a continuous suture in Vicryl 2/0 and we do a single layer in the dermis since the skin of the MWL subjects is very thin. We avoid making knots both at the beginning and at the end of the suture to minimize dermal blood impairments. The suture is blocked at one end with two passages of the thread at the same level and if possible through the thread itself [Figure 3]; at the end, four passages of the thread are made in the opposite direction. It is important that the needle enter and exit the skin perpendicularly in order to leave within the dermis the least amount of thread and minimize the inflammation produced by the suture. Furthermore, the needle exits at the dermo-epidermal junction in order to obtain an optimal margins juxtaposition.

- Detail of the spiral running suture. The suture is blocked with two passages of the thread at the same level and if possible through the thread itself

Postoperative treatment

The patient is checked every 5 days for the first 15 days to replace the medication and every week for the first month. Other controls are made at 3, 6, 12 months. Home therapy includes oral antibiotics for 6 days and low-molecular-weight heparin (enoxaparin) for 10 days as deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis. Patients wear a compressive garment for at least 1 month all day long.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel. A descriptive analysis of all data was first carried out. Then a comparative study was conducted between the LAMeT group and excision-only group. Categorical variables were compared with chi-square analysis or Fisher exact test. Differences between groups were considered significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

All patients treated were female with a mean age at the time of surgery of 44.16 years. Mean weight loss was 61.25 kg (range: 22–91 kg); mean body mass index (BMI) at the time of surgery was 28 kg/m2 (range 22–34,16 kg/m2), maximum BMI was 50.73 kg/m2 (range 41.77–63.29 kg/m2), and delta-BMI was of 23.88 kg/m2 (range 14.77–36.45 kg/m2); in all patients the weight loss was obtained with bariatric surgery [Table 1].

| Overall | Excision-Only | Liposuction-Assisted | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 54 | 28 | 26 | |

| Age at surgery, year | 44,16 (min 25, max 61) | 44,44 (min 25, max 61) | 43,63 (min 36, max 52) | >0.05 |

| Mean weight loss, kg | 61,25 (min 22, max 91) | 58,6 (min 22, max 91) | 66,5 (min 41, max 90) | >0.05 |

| BMI at surgery, kg/m2 | 28 (min 22, max 34,16) | 28 (min 22, max 34,16) | 27,94 (min 22,8, max 33,29) | >0.05 |

| Maximum BMI, kg/m2 | 50,73 (min 41,77, max 63,29) | 49,45 (41,77 max 63,29) | 53,3 (min 47, max 60,95) | >0.05 |

| Change in BMI, kg/m2 | 23,88 (min 14,77, max 36,45) | 23,51 (min 14,77, max 36,45) | 24,61 (min 16,35, max 32,27) | >0.05 |

| No. of comorbidities | 14 | 11 | 3 |

BMI = body mass index.

*Statistically significant difference, P < 0.05

We did not observe statistically significant differences between the two groups by duration of the intervention: 242.19 min (range 60–360 min) in the excision-only group vs. 230 min (range 190–375 min) in the LAMeT group. The hospital stay (2 vs. 5 days, range 3–7 days) and time to drain removal (2.18 vs. 0.25 days) was lower in the LAMeT group. The mean amount of tissue removed was lower in the LAMeT group (385.63 g, range 100–2100 vs. 715.75 g, range 180–1950 g) as a consequence of the liposuction; mean aspirated volume was 1587.5 mL, range 800–2200 mL [Table 2]. The minimum follow-up range was 3 months.

| Overall | Excision-Only | Liposuction-Assisted | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 54 | 28 | 26 | |

| Duration, min | 238,33 (min 60, max 375) | 242,19 (min 60, max 360) | 230 (min 190, max 375) | >0.05 |

| Lipoaspirate, ml | 1058,33 (min 0, max 2200) | 0 | 1587,5 (min 800, max 2200) | >0.05 |

| Resection weight, g | 605, 71 (min 100, max 2100) | 715,75 (min 180, max 1950) | 385,62 (min 100, mac 2100) | >0.05 |

| Time to drain removal, days | 1,54 (min 0, max 5) | 2,18 (min 0, max 5) | 0,25 (min 0, max 2) | <0.05 |

| Days Hospital stay, days | 4 (min 2, max 7) | 5 (min 3, max 7) | 2 | >0.05 |

*Statistically significant difference, P < 0.05

The incidence of postoperative complications was globally 24% (13 patients); the incidence of complications was significantly lower rate in the LAMeT group [3 (3.8%) vs. 10 patients (35.7%); P < 0.05] [Table 3]. No major complications were observed in either group. The incidence of seroma (0 vs. 8 patients) and of wound dehiscence (9 vs. 0 patients) were significantly lower in the LAMeT group while no statistically significant findings were observed for hematoma or infection. Only one patient needed surgical revision. Seroma was treated by fine needle aspiration while wound infection and dehiscence were treated with local medications and oral antibiotics.

| Overall | Excision-Only | Liposuction-Assisted | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 54 | 28 | 26 | |

| Seroma | 8 | 8 | 0 | <0.05 |

| Hematoma | 2 | 2 | 0 | >0.05 |

| Wound dehiscence | 9 | 9 | 0 | >0.05 |

| Wound infection | 1 | 0 | 1 | >0.05 |

| Surgical revision | 1 | 1 | 0 | >0.05 |

| Vulva deformation | 0 | 0 | 0 | >0.05 |

| Scar migration | 9 | 8 | 1 | <0.05 |

| Total patients with complications | 13 | 10 | 3 | >0.05 |

*Statistically significant difference, P < 0.05

A total of nine patients had problems of scars enlargements or migration (eight in the excision-only group vs. one in the LAMeT); no patient experienced deformation of the vulva.

Risk factors for minor complication have found to be smoking (odds ratio 32, P < 0.05) and standard technique (odds ratio 11.67, P < 0.05).

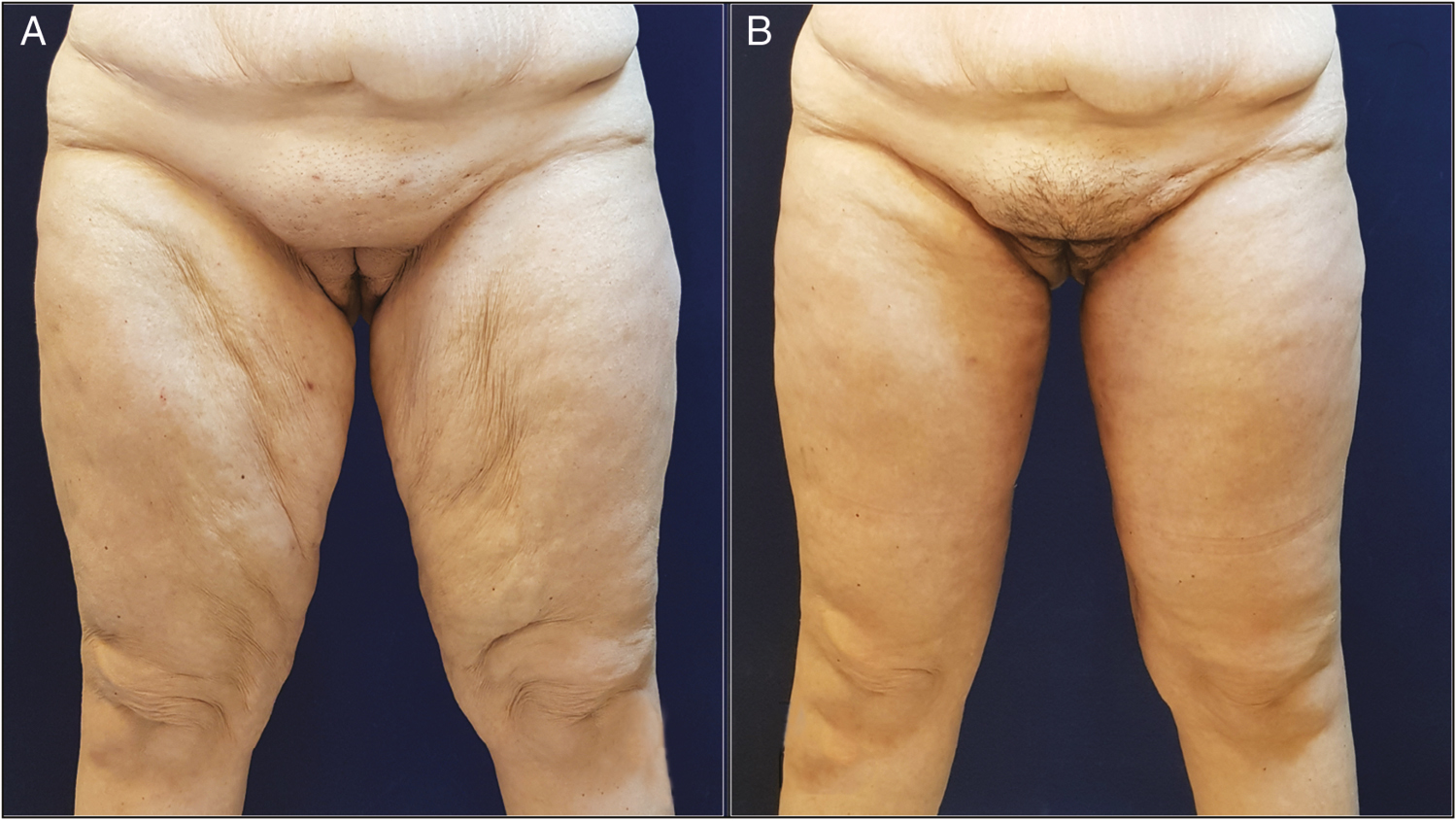

Representative cases of LAMeT technique are shown in Figures 4–7.

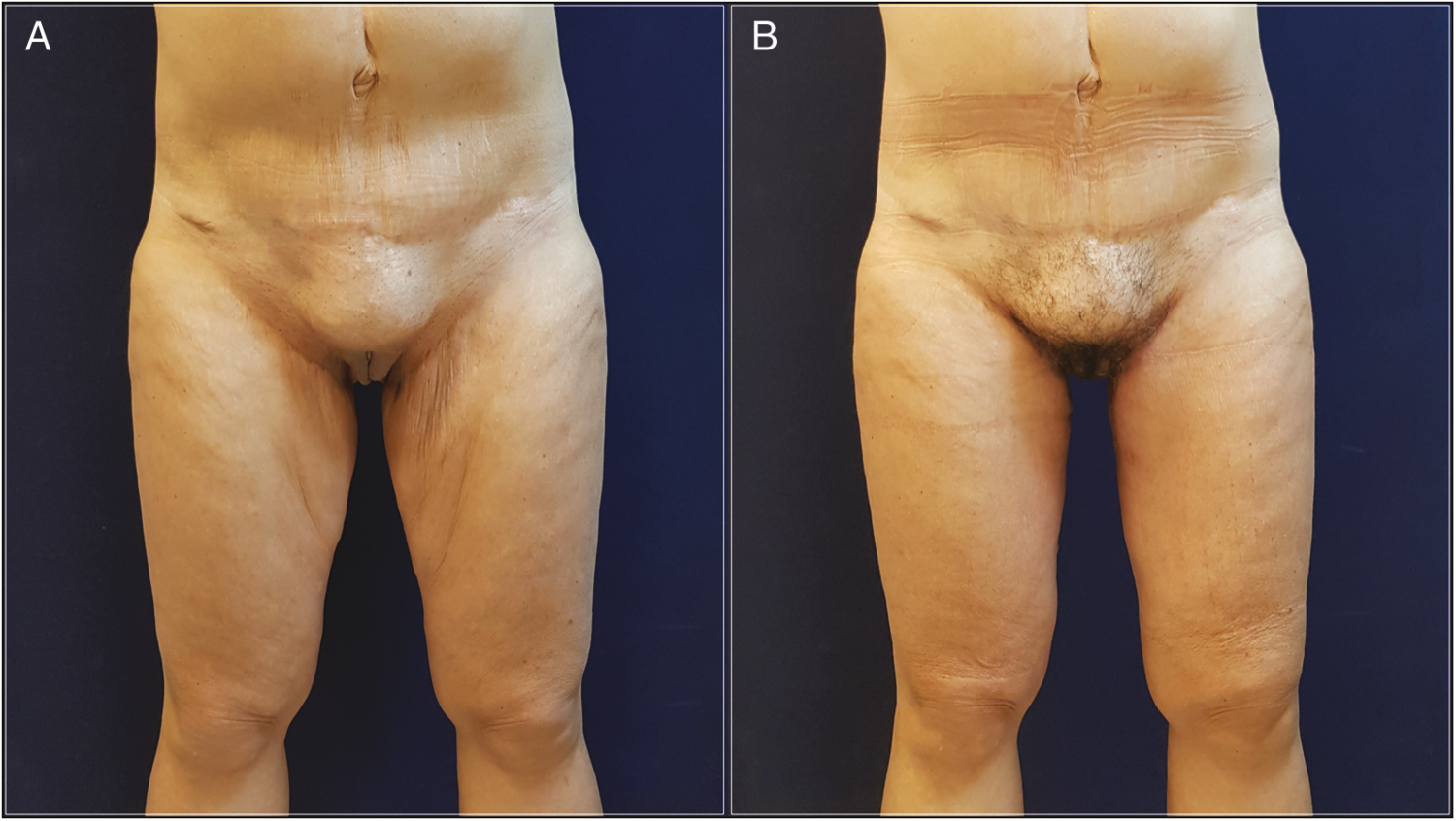

- (A) Anterior view of this 36-year-old woman who underwent LAMeT after gastric bypass and weight loss of 50 kg. (B) Six months postoperatively. Note the improvement even in the medial knee region

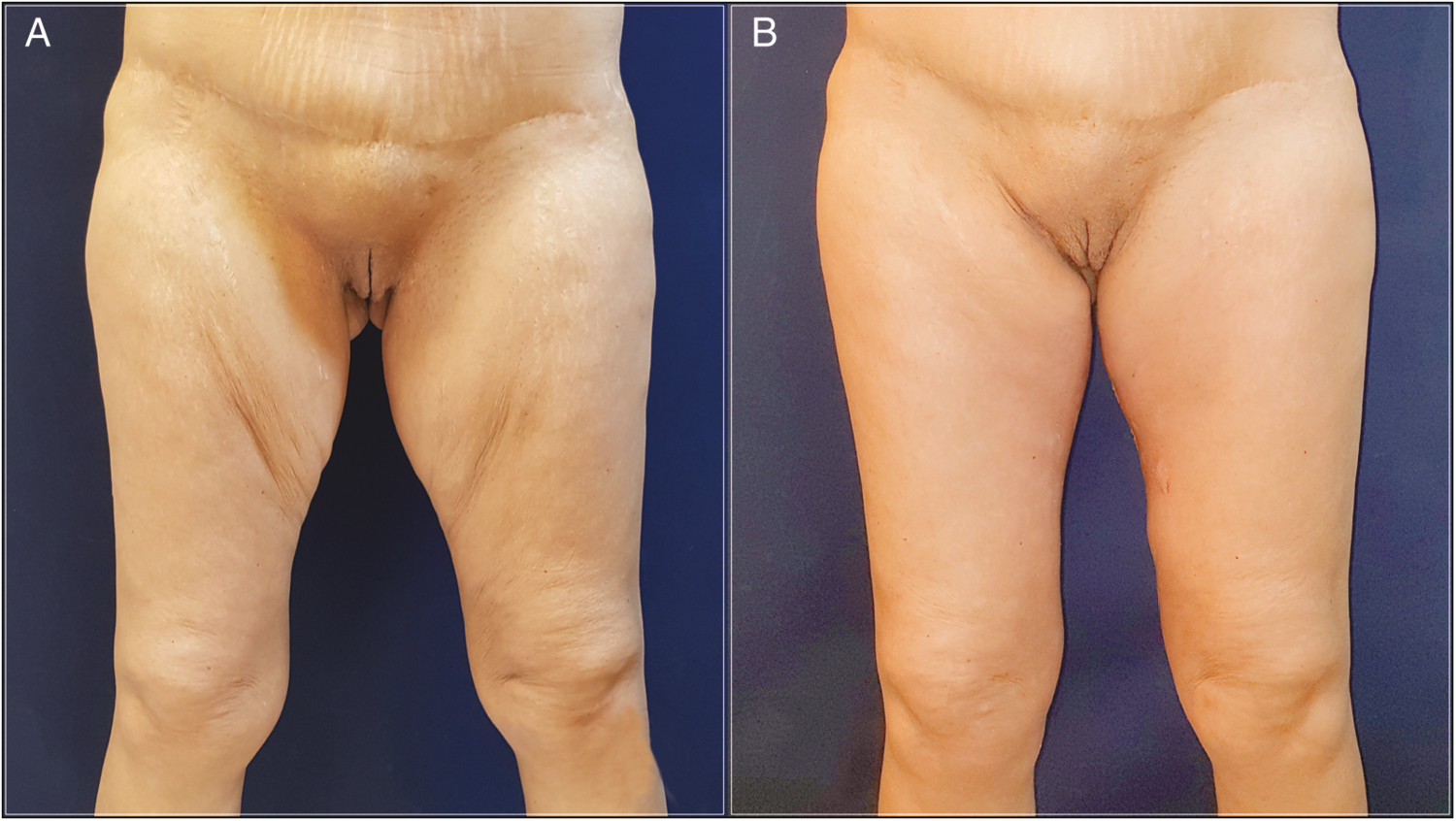

- (A) Anterior and posterior view of this 60-year-old woman who underwent LAMeT after gastric bypass and weight loss of 43 kg. (B) Eight months postoperatively. Note the location and the quality of the scar

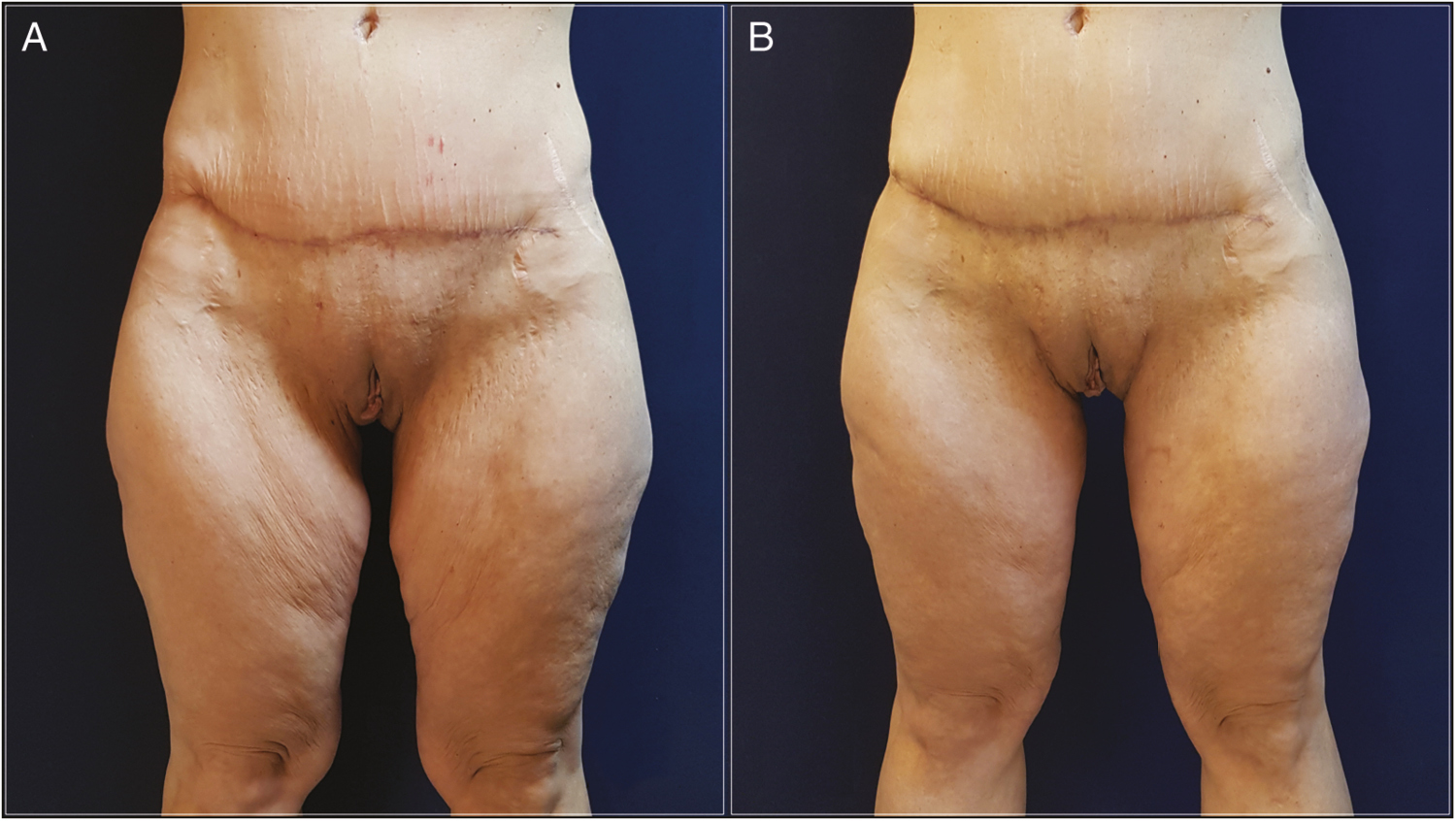

- (A) Anterior view of this 44-year-old woman who underwent LAMeT after gastric bypass and weight loss of 46 kg. (B) Six months postoperatively. Skin excess had been removed with functional and aesthetic improvement

- (A) Anterior view of this 41-year-old woman who underwent LAMeT after gastric bypass and weight loss of 60 kg. (B) Twelve months postoperatively. LAMeT guarantee stable results over time with minimal ptosis recurrence

DISCUSSION

The thigh lifting is a surgical procedure very often requested by post-bariatric patients to remove the excess skin of the thighs following the massive weight loss. The entity of the deformity is classified according to the PRS. PRS is a classification system that allows grading of 10 areas of the body on a four-point scale. The anatomic areas are arms, breasts, abdomen, flank, mons, back, buttocks, medial thighs, hips/lateral thighs, and lower thighs/knees. A four-point grading scale was designed to describe the common deformities found in each region of the body. Each scale ranged from 0 to 3, with 0 indicating an appearance within a normal range, 1 indicating a mild deformity, 2 indicating moderate deformity, and 3 indicating the most severe level of deformity. For each rating the indicated surgical procedures are outlined. These procedures may be performed alone or in combination. Even in the medial thighs area four degrees of deformity are identified[11]: a score of zero represents the normality; if there is an “Excessive adiposity’’ the score is one; a score of two is assigned to a “severe adiposity and/or severe cellulite”; finally, the presence of skin folds determines a score of three. In our study, only patients with a score of two or more were enrolled. It is important to know that this classification was validated only for female patients but not for men who have different massive weight loss deformities.[11] However, no other classification systems were needed in our study as only female patients were included.

In patients that underwent medial thigh lift, the high risk of postoperative complications has led in recent years to an innovative approach that combines liposuction and surgical excision: after the encouraging results of Saldanha[12] and Avelar[13] in lipoaddominoplasty and the positive experience of Le Louarn and Pascal in medial thigh lift,[9] in the recent years other authors have proposed the use of liposuction combined with body contouring techniques.[141516] In fact, liposuction reduces the volume of the thighs without damaging the lymphatic, vascular, and nervous structures and as a consequence it reduces the incidence of postoperative complications. Several studies have shown that liposuction preserves perforating vessels wider than 1 mm: Salgarello has demonstrated how the perforating vessels of the deep inferior epigastric artery are equal in number, diameter, and flow before and 6 months after liposuction.[17] Similar results are reported by Graf et al.[18] about the perforators of the abdominal skin. The fact that we have had no cases of skin necrosis or postoperative persistent edema clearly confirms the benefits of liposuction.

In a recent article, Bertheuil et al.[19] have demonstrated how liposuction also preserves the microcirculation where gas and molecular exchanges occur between blood and tissues. In this study, in fact, the authors have shown that the concentration of endothelial cells is considerably greater in the adipose tissue resected en bloc than the aspirated one; furthermore, in the residual tissue after liposuction the vessels up to 30 mcm in diameter are intact and no larger vessels are found in the aspirated adipose tissue. These results prove that liposuction removes fat in a selective way preserving the microvascular and lymphatic vessels that are instead cut together with the adipose tissue when the excision is performed en bloc.

A particularly fearsome complication of the medial thigh lift is the seroma that may require multiple drains or even surgery[202122]: in our study the incidence of this complication was significantly lower in the LAMeT group thanks to the liposuction that preserves the lymphatic and vascular structures. Another reason is the absence of tissues undermining as tissues are mobilized with liposuction and no dead spaces are created.

We did not observe any differences in during the surgery because the liposuction is performed on a very limited surface so it is completed by the surgeon in a short time; furthermore, thanks to the infiltration of the incision lines, the cut is bloodless and we proceed faster because we do not have to coagulate the dermis.

Another innovative aspect to consider is that in the LAMeT group we did not use drains: this increases patient comfort and at the same time reduces the risk of wound infection. In addition, the lower morbidity of the procedure reduced the average length of hospital stay, allowed patients to return earlier to their work activities and reduced costs related to hospitalization.

A complication reported frequently in the literature in the medial thigh lift is the dehiscence of the sutures[2324] caused by the combination of several factors such as the thin and anelastic skin, the high local humidity, the high frequency of infections and especially the high tension of the sutures. In his initial description, Lewis[1] proposed a technique with horizontal resection in which the traction vector was predominantly vertical so all the weight of the skin flap was supported by the inguinal suture; not by chance there was a high frequency of wound dehiscence, scar migration, and vulva deformation. To avoid these complications, a technique of fascial suspension was proposed a few years later, in which the raised flap was anchored to the Colles fascia.[3] In the LAMeT, the authors have modified the traction vector that is no longer only vertical but vertical and horizontal: this allows to spread the tension of the suture over the entire length of the vertical scar and there is no need of Lockwood fascial suspension. The vertical scar also allows a better lifting of the distal third of the thigh and a refinement of the knee region which is often forgotten in the traditional technique. Some patients may refuse surgery because of the scar length and location: it is, therefore, necessary to explain that the scar is well hidden in frontal vision and that it is necessary to obtain a better and longer lasting result.

The lower incidence of wound dehiscence is also due to a lower thermal damage on the dermis: in fact, thanks to the infiltration of the incision lines, the cut is bloodless and there is no need to coagulate the dermis which then heals better and faster. The absence of thermal injury of the dermis also improves the quality of the scars: in the LAMeT group, in fact, no cases of scar enlargements or migration were observed. Moreover, the spiral running suture causes less dermal inflammation than the traditional closure because the quantity of thread in the width of the dermis is lower and the absence of knots does not cause dermal ischemia.

Other studies are needed to give definitive conclusions on LAMeT; however, positive results encourage the use of the technique especially in patients after massive weight loss.

CONCLUSIONS

The medial thigh lift is a really popular surgical procedure among post-bariatric patients because the cutaneous excess in the inner thigh can cause functional impairment, frequent cutaneous infections, as well as psychological distress. However, even if widespread it is associated with a high incidence of post-operative complications. The LAMeT technique preserves the great majority of lymphatics and blood vessels and nerves and allows a more anatomical resection of the excess skin. Thus reduces post-operative complications and allows the patient to heal faster. The encouraging results of the LAMeT as well as patient satisfaction have convinced the Authors to completely abandon the standard technique.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Correction of ptosis of the thighs: the thigh lift. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966;37:494-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgical reduction of the abdomen, thigh, and buttocks. Surg Clin North Am. 1971;51:479-89.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fascial anchoring technique in medial thigh lifts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82:299-304.

- [Google Scholar]

- The “Crural Meloplasty” for lifting of the thighs. Clin Plast Surg. 1975;2:495-503.

- [Google Scholar]

- Integration of the vertical medial thigh lift and monsplasty: the double-triangle technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:153e-4e.

- [Google Scholar]

- The scarpa lift—a novel technique for minimal invasive medial thigh lifts. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1975-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Two cases of lower body contouring with a spiral and vertical medial thigh lift. Arch Plast Surg. 2012;39:67-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complications associated with medial thigh lift: a comprehensive literature review. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:191-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- A classification of contour deformities after bariatric weight loss: the Pittsburgh Rating Scale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1535-44; discussion 1545-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abdominoplasty without panniculus undermining and resection: analysis and 3-year follow-up of 97 consecutive cases. Aesthet Surg J. 2002;22:16-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Liposuction-assisted medial thigh lift in obese and non obese patients. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:217-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Four-step medial thighplasty: refined and reproducible. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:717e-25e.

- [Google Scholar]

- An improved dual approach to post bariatric contouring—staged liposuction and modified medial thigh lift: a case series. Indian J Plast Surg. 2014;47:232-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of liposuction on inferior epigastric perforator vessels: a prospective study with color Doppler sonography. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:346-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipoabdominoplasty: liposuction with reduced undermining and traditional abdominal skin flap resection. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2006;30:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Liposuction preserves the morphological integrity of the microvascular network: flow cytometry and confocal microscopy evidence in a controlled study. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36:609-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- New management algorithm for lymphocele following medial thigh lift. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:1450-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thighplasty after bariatric surgery: evaluation of lymphatic drainage in lower extremities. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1160-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intraoperative lymphatic mapping to treat groin lymphorrhea complicating an elective medial thigh lift. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;48:205-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complications in postbariatric body contouring: postoperative management and treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:1693-700.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medial thigh lift in the massive weight loss population: outcomes and complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:98-106.

- [Google Scholar]