Translate this page into:

Pain and Anxiety Management Practices in Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A UK National Survey

Address for correspondence: Dr Brogan K. Salence, Dermatology Department, Churchill Hospital, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Churchill Hospital, Old Road, Headington, Oxford OX3 7LE, UK. E-mail: Brogan.salence@ouh.nhs.uk

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Dear Editor,

Mohs surgeons are required to manage pain and anxiety related to cutaneous surgery. The majority of patients report some degree of pain on the day of the procedure which decreases thereafter. Intraoperatively, pain has been reported to occur more commonly in patients who spent a longer time in surgery and had three or more Mohs layers.[1] Anxiety can worsen pain, prolong recovery, and increase the risk of complications.[2] Together, these factors may negatively affect patient perception of care and overall satisfaction of Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). We aimed to assess the variations in the management of peri-procedural pain and anxiety through a nationally distributed survey to the members of the British Society for Dermatological Surgery in December 2019. Of the 84 Mohs surgeons in the UK, we received 36 responses (43% response rate). Mohs surgeons from 24 centers were represented with 44.4% (16/36) having more than 10 years’ experience with most respondents performing more than 100 cases per year (27/36.75%). The questionnaire and results are shown in [Table 1].

| Results, n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Do you use anxiolytics if required during Mohs? | |

| Yes | 15 (41.7) |

| No | 21 (58.3) |

| Do you offer the option of playing music during surgery? | |

| Yes | 27 (75) |

| No | 4 (11.1) |

| Sometimes | 5 (13.9) |

| What size needle do you most commonly use to inject local anesthetic? | |

| 30 Gauge (G) | 18 (50) |

| 27G | 13 (36.1) |

| 25G | 2 (5.6) |

| Other | 3 (8.3) |

| At what angle do you inject local anesthetic? | |

| 45° | 30 (83.3) |

| 90° | 4 (11.1) |

| Other | 2 (5.6) |

| Do you use bicarbonate to buffer your local anesthetic? | |

| Yes | 5 (13.9) |

| No | 31 (86.1)) |

| Do you use bupivacaine? | |

| Yes | 29 (80.5) |

| No | 6 (16.7) |

| Other | 1 (2.8) |

| Do you warm the local anesthetic to room temperature? | |

| Always | 24 (66.7) |

| Very often | 5 (13.9) |

| Sometimes | 5 (13.9) |

| Rarely | 2 (5.6) |

| Never | 0 |

| Do you use nerve blocks? | |

| Always wherever possible | 9 (25) |

| Very often | 9 (25) |

| Sometimes | 13 (36.1) |

| Rarely | 5 (13.9) |

| Never | 0 |

| Do you advice analgesia postoperatively? | |

| Always | 16 (44.4) |

| Very often | 8 (22.2) |

| Sometimes | 8 (22.2) |

| Rarely | 3 (8.1) |

| Never | 1 (2.8) |

| What analgesia are you most likely to advise? | |

| NSAIDs | 0 |

| Tramadol | 0 |

| Codeine | 1 (2.8) |

| Paracetamol | 33 (91.7) |

| No analgesia | 0 |

| Other | 2 (5.6) |

| Which pain assessment tool do you use? | |

| Visual analog scale | 4 (11.1) |

| Numerical pain score | 1 (2.8) |

| Wong–Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale | 0 |

| Verbal rating scale | 5 (13.9) |

| None | 26 (72.2) |

| Do you perform patient-reported pain scores to assess your practice? | |

| Yes | 3 (8.3) |

| No | 28 (77.8) |

| Sometimes | 5 (13.9) |

Preoperatively, the majority did not use anxiolytics (21/36; 58.3%) but 75% (27/36) of the respondents did offer the option of playing music during surgery. Music, a subtle form of distraction, reduces anxiety in patients undergoing MMS and may reduce the need to use anxiolytics.[2] The addition of sodium bicarbonate to lignocaine raises the pH and reduces pain during infiltration.[3] However, sodium bicarbonate was used seldomly (13.9%; 5/36) whereas 80.5% (29/36) used the longer-acting bupivacaine. In our survey, the majority used a 30-Gauge needle which is in line with evidence that suggests that needle insertion pain has an inverse relation to the diameter of the needle.[4] Mohs surgeons with 10 years or less experience were more likely to use nerve blocks very often or wherever possible (12/20; 60%) in comparison to surgeons with more than 10 years’ experience (6/16; 37.5%), suggesting a change in practice more recently.

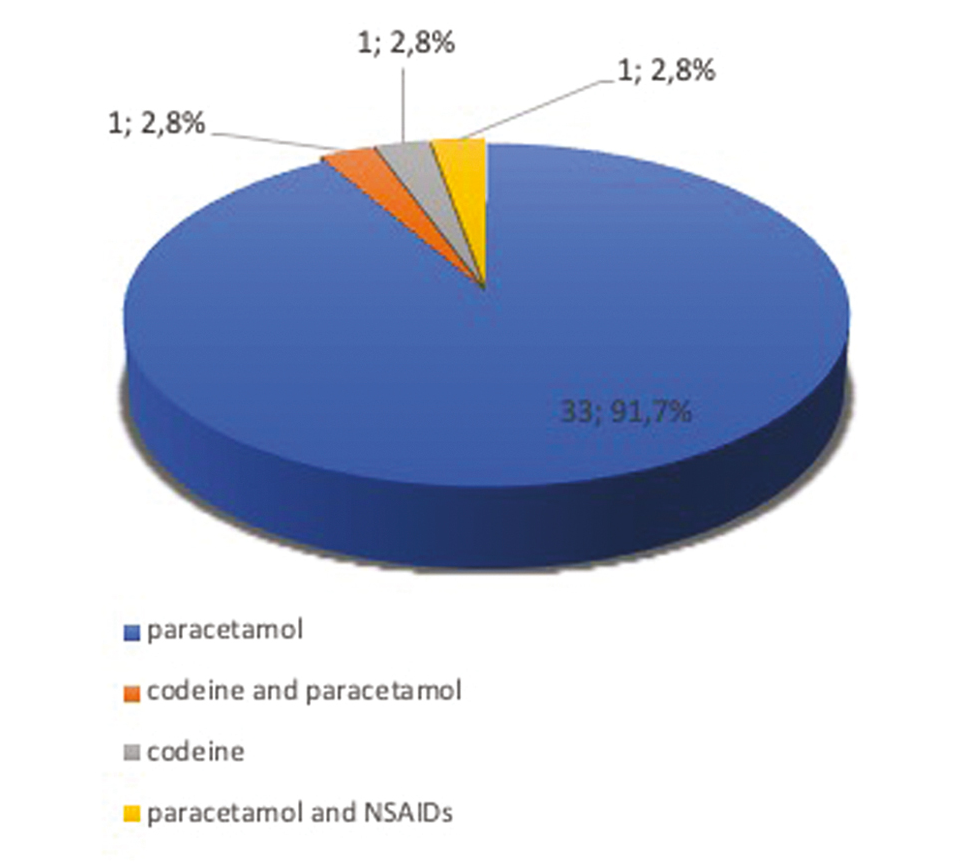

Postoperatively, paracetamol was advised by 91.7% (33/36), whereas the combination of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with paracetamol was advised by only one surgeon (1/36; 2.8%) [Figure 1]. The combination of paracetamol and ibuprofen has been shown to be superior in controlling postoperative pain after MMS when compared with paracetamol and codeine, and paracetamol alone in a small randomized controlled trial.[5] A larger systematic review also found no increased risk in post-operative bleeding after tonsillectomy.[6] We found that 72.2% (26/36) of the respondents did not use a pain assessment tool. This is a simple and effective adjunct which can be used to identify patients in pain and may improve the quality of their care. One surgeon suggested the use of “talkaesthesia,” which is the gentle distractive conversation while undertaking a procedure.

- Number of participants who recommended specific analgesia postoperatively, n = 36 (%)

The rapid expansion of MMS in the UK over the past decade means that more complex, time-consuming reconstructions are being performed in an outpatient setting under local rather than general anesthesia. It is imperative that there is an emphasis on patient comfort which may in turn encourage health-seeking behavior. We highlight the benefit of sodium bicarbonate buffering of lignocaine to reduce pain and the use of music to reduce anxiety in patients undergoing MMS. Further studies evaluating optimal analgesia regimen and the use of NSAIDs in MMS are required.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Assessment of intraoperative pain during Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS): An opportunity for improved patient care. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:590-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Music reduces patient anxiety during Mohs surgery: An open-label randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:298-305.

- [Google Scholar]

- Randomised control trial of pH buffered lignocaine with adrenaline in outpatient operations. Br J Plast Surg. 1998;51:385-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pain following controlled cutaneous insertion of needles with different diameters. Somatosens Mot Res. 2006;23:37-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen, acetaminophen and ibuprofen, and acetaminophen and codeine for postoperative pain relief after Mohs surgery and cutaneous reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1007-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- A 2013 updated systematic review & meta-analysis of 36 randomized controlled trials; no apparent effects of non steroidal anti-inflammatory agents on the risk of bleeding after tonsillectomy. Clin Otolaryngol. 2013;38:115-29.

- [Google Scholar]