Translate this page into:

A Rare Case of Nasal Glial Heterotopia in an Infant

Address for correspondence: Dr. Nadeem Tanveer, Department of Pathology, University College of Medical Sciences, Delhi 110095, India. E-mail: ntobh104@yahoo.co.in

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Glial heterotopias are the displacement of neuroglial tissue in extracranial sites. Nasal glial heterotopias can be of three types-extranasal, intranasal and mixed. Root of the nose is the most common location. These are rare anomalies with an incidence of 1 case in 20,000–40,000 live births. Here we report the case of a 6-month-old infant with a congenital mass located at the root of the nose. Non-contrast computed tomography studies showed no evidence of intracranial communication of the lesion. The mass was excised, and on histopathological examination, it showed glial tissue with astrocytes in a fibrillary background and fibroconnective tissue. Masson’s trichrome stain showed the red staining of the glial tissue, whereas the background fibrosis was stained blue. On immunohistochemistry, glial fibrillary acidic protein was positive. Hence, the diagnosis of nasal glial heterotropia was made. The patient had an uneventful postoperative period.

Keywords

Nasal glial heterotopia

nasal glioma

infant

INTRODUCTION

Glial heterotopias are the displacement of neuroglial tissue in extracranial sites. These are rare anomalies, approximately occurring in 1:20,000–40,000 births. They are benign, congenital, and often located in the midline.[1] Nasal glial heterotopias (NGHs), previously also known as nasal gliomas, as the name suggests, are the displacement of mature glial tissue as a mass inside (intranasal) or outside the nose (extranasal) without connection to the cranial cavity. Root of the nose is the most common location in case of extranasal glioma.[2] Midline lesions in infants include the following: hemangiomas, gliomas, dermoid cysts, and encephaloceles. Radiographic examination (computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging) is essential to rule out possible communication of the mass with intracranial space and to assess bony defects.[3] Total surgical excision is advised early in life to avoid complications such as meningitis, brain abscess for intranasal gliomas, and cosmetic complications for extranasal gliomas.[4]

CASE HISTORY

A 6-month-old infant was brought to the hospital with a mass present at the root of the nose [Figure 1A]. The mother said the mass had been present since birth and had increased gradually with time. The child had no other symptoms such as dyspnea or difficulty in feeding. There was no change in size when the child cried. There was no other swelling anywhere else on the body, and no delay in developmental milestones was noted. Biopsy is not advised in congenital midline masses because if there is an intracranial connection, it can cause cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. A non-contrast computed tomography (NCCT) of the mass had been carried out when the child was 1 month of age and it showed a soft tissue density space occupying lesion measuring 20 × 20 × 13 mm. No communication with nasal cavity or brain was seen. No other abnormality in the brain parenchyma or the paranasal sinuses was reported. Possibility of a benign lesion was suggested [Figure 2].

- (A) Preoperative photograph of the child with swelling at the root of nose. (B) Postoperative photograph of the child

- NCCT showing no connection between the mass and the dura or brain

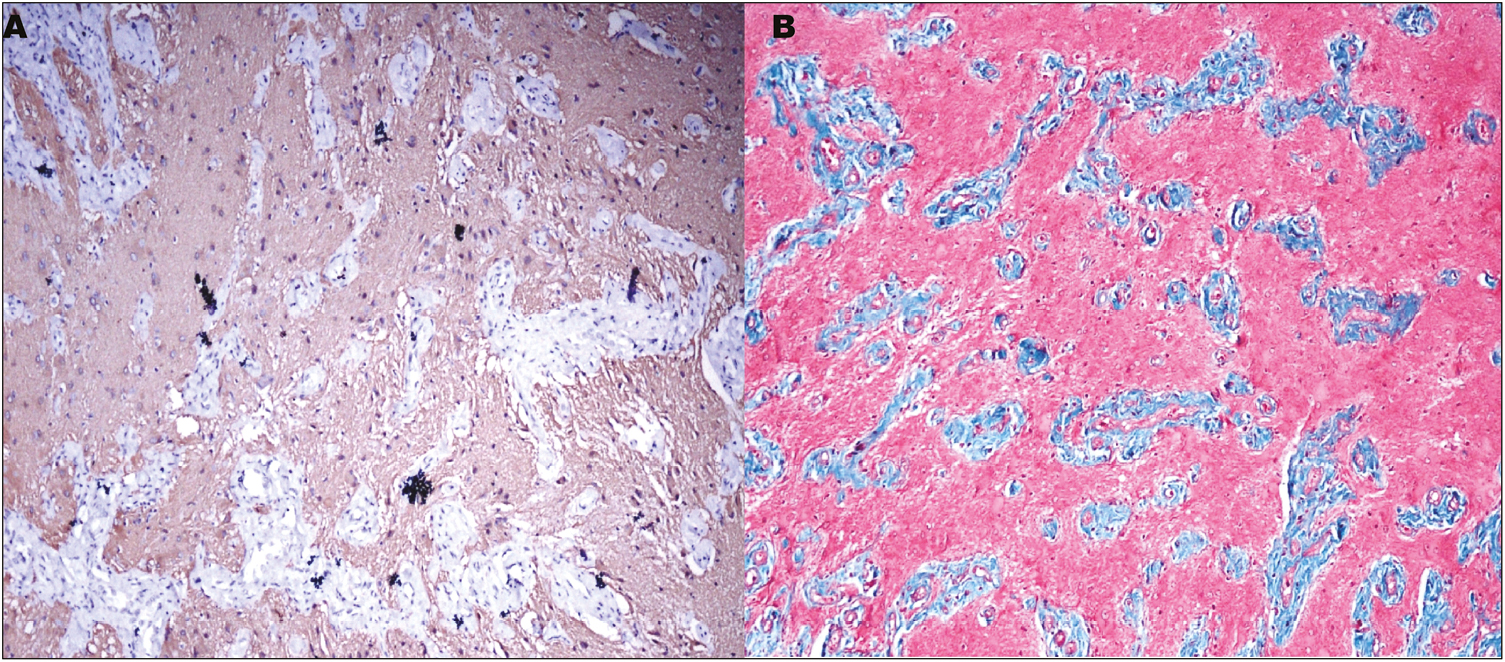

An excision biopsy was performed. There were no postoperative complications [Figure 1B]. The excised specimen was sent for histopathological examination. On gross examination, it was found to be a single gray-brown globular soft tissue piece measuring 2.5 × 1.5 × 1 cm [Figure 3A]. The outer surface was unremarkable, and the cut section was gray-white and solid. The histopathological examination showed glial tissue with astrocytes in a fibrillary background along with fibroconnective tissue. No leptomeningeal, ependymal, or choroid plexus tissue was identified [Figure 3B and C]. Masson’s trichrome stain showed red staining of the glial tissue, whereas the background fibrosis was stained blue. On immunohistochemistry, glial fibrillary acidic protein was positive [Figure 4A and B].

![(A) Cut section of the mass showing homogenous gray-white solid soft tissue lesion. No hemorrhage or necrosis is seen. (B) Glial tissue with intervening fibrosis (hematoxylin and eosin [H and E], ×100). (C) Astrocytes in a fibrillary background (H and E, ×100). Few gemistocytes seen (arrow)](/content/173/2020/13/3/img/JCAS-13-233-g003.png)

- (A) Cut section of the mass showing homogenous gray-white solid soft tissue lesion. No hemorrhage or necrosis is seen. (B) Glial tissue with intervening fibrosis (hematoxylin and eosin [H and E], ×100). (C) Astrocytes in a fibrillary background (H and E, ×100). Few gemistocytes seen (arrow)

- (A) The glial tissue is immunopositive for GFAP (immunohistochemistry, ×100). (B) The glial tissue stained dusky pink to red in color on Masson’s trichrome stain (×100), whereas the fibrous tissue stained blue

Final diagnosis of NGH was made. No recurrence was observed till 1 year of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

NGH is the presence of mature glial tissue outside the cranial cavity. It has also been called nasal glioma by some authors. It is usually present at birth or diagnosed in early childhood.[5] A total of 264 cases have been reported in world literature of this rare entity. It was first described by Reid in 1852.[6] Approximately 90% of the cases are diagnosed before 2 years of age. In this case, the lesion had been identified since birth. NGHs can be located inside or near the nasal cavity, with 60% of cases located extranasally, 30% located intranasally, and 10% both extranasally and intranasally—mixed type.[4] Extranasal glial heterotopias are firm, smooth masses that do not pulsate or expand during crying, coughing, or straining.[5] They may be associated with hypertelorism. Although NGH grows at a very slow rate and has no malignant potential, in untreated cases, complications such as distortion of septum, nasal bone, or infections have been described.[6]

NGH may represent encephaloceles, which have lost their intracranial connection. Approximately 15%–20% of cases may have a thin stalk of fibrous tissue connected to the dura as a remnant.[6] Intranasal NGH is more likely to have such a connection as compared to extranasal types. In our case, no such connection was found at surgery.

NGHs should be differentiated from dermoid cyst and encephaloceles as they can all manifest as midline nasal masses. Encephaloceles are extracranial hernias of the meninges and/or brain caused by congenital defects in the skull. Because they have an intracranial connection, there is pulsation and expansion of the mass with crying, straining, or compression of the jugular vein (Furstenberg test).[3] In our patient, the mass showed no pulsation and expansion during crying or straining, and no developmental anomalies and no intracranial connection on NCCT, thus making the diagnosis of encephaloceles unlikely.

Nasal dermoid cyst is another differential for NGH. The differential can be made on histopathology as the dermoid cysts are lined by keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, containing skin tissues or dermal appendages (e.g., hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and sweat glands), and NGH shows mature glial tissue.[5] The rare components of NGH reported include—retinal pigmented epithelium, choroid plexus, and ependymal clefts.[6]

Facial midline swellings are a common source of confusion, and biopsy should not be carried out as a common mode of diagnosis as there is a risk of CSF leak. In our case, NCCT showed no communication with brain or meninges. Hence, excision biopsy was performed.

Complete surgical excision of NGHs is curative.[7] However, a postoperative recurrence rate of 4%–10% has been reported.[6] Our patient was followed up for 1 year postoperatively, and did not report any recurrence. If there is no intracranial communication, an external approach is adequate. However, neurosurgical advise may be sought if a previously unrecognized tract going up to the skull base is found on surgery. Complete and early excision prevents complications, and better cosmetic results are achieved.[4]

Extranasal sites of glial heterotopia include lung, uterine cervix, endometrium, lip, tongue, and maxilla.[8]

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Resection of nasal glial heterotopia using a nasal subunit approach. Ochsner J. 2018;18:176-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A CARE-compliant article: Extranasal glial heterotopia in a female infant: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12000.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case of nasal glial heterotopia in an adult. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2014;2014:354672.

- [Google Scholar]

- Central nervous system tissue heterotopia of the nose: Case report and review of the literature. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2009;29:218-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nasal glial heterotopia: Four case reports with a review of literature. Oral Maxillofac Surg Cases. 2019;5:e100107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nasal glial heterotopia: A clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic analysis of 10 cases with a review of the literature. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2003;7:354-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glial heterotopia of maxilla: A clinical surprise. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2011;16:58-60.

- [Google Scholar]