Translate this page into:

Awareness level regarding adverse reactions caused by cosmetic products among indian women: A cross-sectional study

*Corresponding author: Virendra S. Ligade, Department of Pharmacy Management, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India. virendra123sl@gmail.com

-

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Nayak M, Prabhu SS, Sreedhar D, Muragundi PM, Janodia MD, Ligade VS. Awareness level regarding adverse reactions caused by cosmetic products among Indian women: A cross- sectional study. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2025;18:101-7. doi: 10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_164_22

Abstract

Objectives:

Cosmetics have become a part of the daily grooming routine. The majority of women utilize cosmetics to some extent without much knowledge about their side effects. Adverse reactions can occur immediately after the application of the product or during their long-term usage. Adverse reactions related to cosmetics go unnoticed and under-reported. Women are most likely affected by adverse reactions compared with men. This study aimed to analyze the awareness level among Indian women regarding adverse reactions caused by cosmetic products.

Material and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was performed among South Indian women from March 2021 to July 2022. A sample of 400 each, working women (WW) and nonworking women (NW), was selected using the snowball technique, and data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire through Google Forms. Data were analyzed by using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21 and descriptive statistics were applied.

Results:

In total, 791 (98.8%) participants used various cosmetic products. A total of 163 (41.1%) WW and 139 (35.1%) NW experienced adverse effects due to the use of cosmetic products. Skincare products cause more adverse reactions compared with other cosmetic products. The primarily affected body site was the face. The majority of respondents solved their adverse reactions problem by adopting self- medication.

Conclusion:

A significant percentage of the respondents experienced adverse side effects due to the usage of cosmetics. Awareness regarding the possibility of cosmetic-induced adverse effects, as well as the proper use of cosmetics to reduce these adverse effects is imperative. Implementation and appropriate application of cosmetovigilance can aid in limiting or eliminating the presence of dangerous substances in cosmetics and also helps in decreasing adverse events.

Keywords

Adverse events

Cosmetics

Indian

Women

INTRODUCTION

“Cosmetics are articles meant to be rubbed, poured, sprinkled, sprayed, introduced into, or otherwise applied to the human body for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering the appearance.”1,2 Around 90% of all cosmetics sold in the world today are probably cosmeceuticals. “Cosmeceuticals are a new category of items that fall between cosmetics and pharmaceuticals and are meant to improve both the health and appearance of the skin.”3 Although cosmetics can help consumers feel more beautiful, they can cause untoward effects (adverse events). Cosmetics have become a part of everyone’s daily grooming routine, particularly among fashionistas and young girls.4-6 Cosmetic manufacturers can market their products without the consent of the authorities, and there are no proper guidelines for cosmetics manufacture or marketing in India. Furthermore, a cosmetic producer is not required to report injuries caused by its product, and they can add any component to improve their brand without seeking approval. This structure exposes customers to the harmful effects of cosmetics.7 Many consumers who use cosmetics are unconcerned about the effects on their skin and assume that cosmetic products are safe and pose no risk to human health.8 Females are most likely affected because they tend to use more cosmetic products than men.9 Cosmetics can make users feel more attractive, but they can also have undesirable effects. According to some studies, the presence of a variety of ingredients, fragrances, and preservatives in cosmetic products, individually or combined, are the main reasons for toxicity exposure to consumers.10,11 Allergic contact dermatitis, scalp injury, acute hair loss, acne, photo-allergic dermatitis, onycholysis, etc., can occur as adverse reactions due to cosmetics.12-14 These can occur immediately after the application of the cosmetic product or on long-term usage. In Western countries, cosmetics regulatory authorities have established criteria for cosmetics’ safety, efficacy, and quality to reduce the unfavorable effects of cosmetics. In developing countries, there is still a lack of population awareness about proper cosmetics use, as well as a lack of proper adverse effect reporting systems.15 In our country, the number of documented adverse cosmetic reactions is currently quite low due to self-diagnosis and self-medication, which are common in the presence of mild-to-moderate skin reactions. According to the literature, promoting cosmetovigilance and running awareness programs for cosmetic products can assist in reducing negative outcomes.9,16 The present study attempted to evaluate the awareness level regarding adverse reactions caused by cosmetic products among women of different age groups in India.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Research design

A cross-sectional study design was used to assess awareness levels regarding adverse reactions caused by cosmetic products. Working women (WW) and nonworking women (NW) from rural and urban regions of South India were selected for the study. WW are those who earn their livelihood by going out of home for work. NW are defined as those who work in their homes, farms, and surroundings, that is, those who do not go out and face strangers/colleagues at work. Inclusion criteria: all women over the age of 18 and under the age of 60 were selected as respondents, and those who gave their consent to anticipate in the study were included. Exclusion criteria: respondents who were unwilling to participate voluntarily in the study and who were not sure whether their condition was due to cosmetics or other causes.

Data collection

To collect data for this study, a pilot-tested, self-administered questionnaire was used. The questionnaire was created by the authors and validated. A designed questionnaire was sent to five experts for validating the content and fulfillment of the objectives of the study. It was approved by the subject experts in the field of cosmetics. All the questions were closed-ended. Open-ended questions were avoided to maintain a consistent format for the output. The information gathered from responders was kept strictly confidential. The questionnaire was divided into three sections. Part one covered the respondent’s general information (sociodemographic data). Part two was the utilization pattern of products by the respondents. Part three dealt with the adverse events caused by the use of cosmetic products. A nonprobability sampling technique and a snowball-sampling methodology were selected. Data was collected through Google Forms. A sample of 400 each, WW and NW, was considered and calculated by using the estimation of the proportion. Variables: the dependent variables were self-reported adverse reactions and cosmetics utilization, whereas the independent variables of the study included: age, working status, occupation, and the number of cosmetics applied per day.

Data processing, analysis, and interpretation

The data were collected from March 2021 to July 2022. The information gathered from the respondents was recorded and documented. For analyzing the data, SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences Program manufactured by New York, USA) version 21 and Microsoft Office Excel 2007 manufactured in Washington, USA were used. The questionnaire was analyzed with the help of frequencies and percentages and was represented with the help of tables and figures. For categorical data, the Chi-square test was used to assess the difference between groups. A P-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics

A sample of 400 each, WW and NW, was selected for the study. The age of the study participants ranged from 18 to 60 years old.

Out of 800 total women, the majority belonged to the age group of 18–28 years (480), followed by 29–39 years (201), 40–50 years (97), and 51–60 years (22). Out of 480 women who belonged to the age group of 18–28 years, around 472 women were using some cosmetic products or the other. Out of 201 women who belonged to the age group of 29–39 years, around 200 women were using cosmetics. Remaining all 119 old-age women were using cosmetics.

Out of 400 each WW and NW, around 396 WW and 395 NW reported that they use some sort of cosmetics products [Table 1].

| Variable | Category | Number of participants | Cosmetic use | Sometimes | Chi-square test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| Age | 18–28 | 480 (60.0) | 298 (62.08) | 8 (1.66) | 174 (36.25) | 0.6923 |

| 29–39 | 201 (25.12) | 131 (25.1) | 1 (0.1) | 69 (16.4) | ||

| 40–50 | 97 (12.12) | 62 (12.1) | 0 (0.0) | 35 (7.8) | ||

| 51–60 | 22 (2.75) | 13 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (1.6) | ||

| Working status | Working | 400 (50.0) | 264 (66.0) | 4 (1.0) | 132 (33.0) | 0.2125 |

Cosmetic utilization practices

Out of 800 respondents, 791 (98.8%) participants used cosmetic products. Among those, 174 (43.9%) WW and 181 (45.8%) NW had the habit of using more than three cosmetics products per day. A very few WW (90 [22.7%]) and NW (79 [24.3%]) had the practice of consulting a dermatologist before using the products. However, 145 (36.6%) WW and 152 (38.4%) NW had the habit of reading the label printed on the cosmetic products (content, manufacturer details, safety, storage, etc.). Around 241 (30.4%) respondents said “sometimes” they read the label. The majority of 232 (58.5%) WW and 234 (59.2%) NW did not follow the instructions given on the products. About 349 (88.1%) WW and 358 (90.6%) NW noticed the expiry date of the products before using them.

About 222 (56%) WW and 240 (60.7%) NW are not aware of the presence of heavy metals in cosmetics products. A very few women had undergone sensitivity (94 [23.7%] WW and 79 [20%] NW) and patch tests (115 [29%] WW and 95 [24%] NW) before using the products.

This study found that out of 791 participants who used cosmetic products, around 314 (79.2%) WW and 297 (75.1%) NW were not aware of the reporting of adverse events or cosmetovigilance system. Remaining 180 women were aware of the reporting system.

As the P value is more than 0.05 for all the variables, a statistically significant difference was not found between cosmetic utilization-related practices and the working status of women. The cosmetic use-related practices among the study participants are given in Table 2.

| Variable | Category | Working status | Total | Chi-square | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working (396) | Nonworking (395) | ||||

| Per day use of cosmetics | Two | 147 (37.12) | 153 (38.7) | 300 (38.12) | 0.438 |

| Three | 75 (18.9) | 61 (15.4) | 136 (17.19) | ||

| More than three | 174 (43.9) | 181 (45.8) | 355 (44.8) | ||

| Consulting dermatologist before using the product | Yes | 90 (22.7) | 79 (20.0) | 169 (21.3) | 0.386 |

| No | 306 (77.2) | 316 (80) | 622 (78.6) | ||

| Label reading | Yes | 145 (36.6) | 152 (38.4) | 297 (37.5) | 0.769 |

| No | 61 (15.4) | 63 (15.9) | 124 (15.6) | ||

| Sometimes | 120 (30.3) | 121 (30.6) | 241 (30.4) | ||

| Always | 70 (17.6) | 59 (14.9) | 129 (16.3) | ||

| Following the label instructions | Yes | 144 (36.3) | 129 (32.6) | 273 (34.5) | 0.166 |

| No | 232 (58.5) | 234 (59.2) | 466 (58.9) | ||

| Sometimes | 20 (5.0) | 32 (8.1) | 52 (6.5) | ||

| Awareness on the presence of heavy metals in cosmetics | Yes | 174 (43.9) | 155 (39.2) | 329 (41.5) | 0.194 |

| No | 222 (56.0) | 240 (60.7) | 462 (58.4) | ||

| Awareness about the expiry date | Yes | 349 (88.1) | 358 (90.6) | 707 (89.3) | 0.299 |

| No | 47 (11.8) | 37 (9.3) | 84 (10.6) | ||

| Perform sensitivity test before use | Yes | 94 (23.7) | 79 (20.0) | 173 (21.8) | 0.229 |

| No | 302 (76.2) | 316 (80.0) | 618 (78.1) | ||

| Perform a patch test before use | Yes | 115 (29.0) | 95 (24.0) | 210 (26.5) | 0.126 |

| No | 281 (70.9) | 300 (75.9) | 581 (73.4) | ||

| Awareness on cosmetovigilance system | Yes | 82 (20.7) | 98 (24.8) | 180 (22.7) | 0.176 |

| No | 314 (79.2) | 297 (75.1) | 611 (77.2) | ||

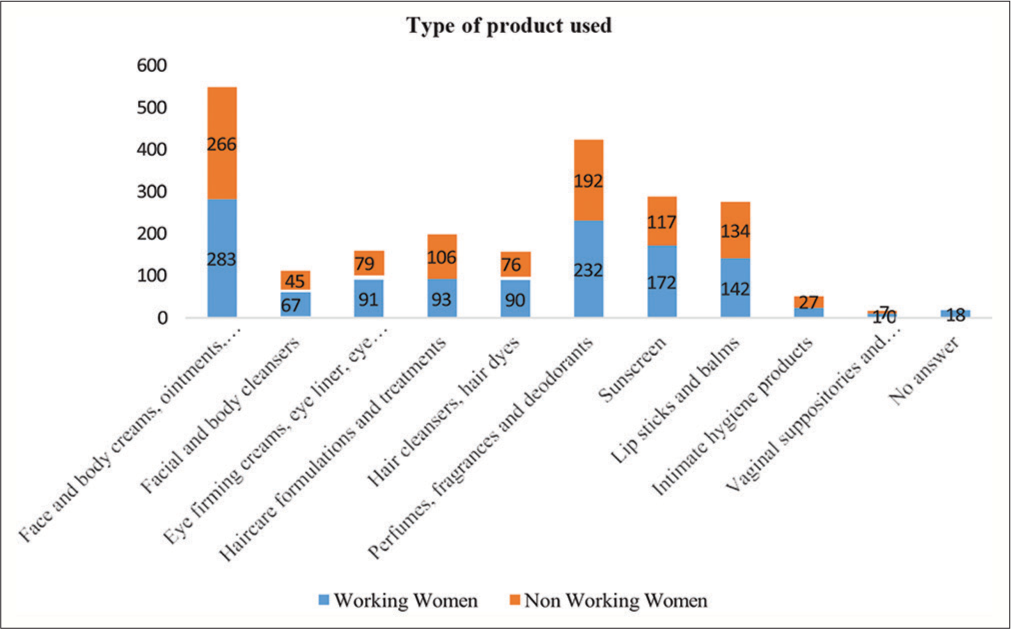

The majority of the WW and NW were using face and body creams, ointments, and lotions, followed by perfumes, fragrances, and deodorants [Figure 1].

- Type of cosmetic products used ** (** multiple responses obtained).

Out of 791 women, 163 (41.1%) WW and 139 (35.1%) NW experienced adverse effects due to the use of cosmetics products. According to 108 (27.2%) WW and 87 (22%) NW, adverse reactions were more due to skincare products followed by hair care products (54 [13.6%] WW and 48 [12.1%] NW). Regarding the nature of the reported adverse cosmetics events, 98 (24.7%) WW and 79 (20%) NW experienced a skin reaction, whereas 25 (6.3%) WW and 22 (5.5%) NW experienced systemic events. The most affected body parts were the face for both WW (86 [21.7%]) and NW (62 [15.6%]), followed by hair. The most common adverse effect found on the face was acne in 58 (14.6%) WW and 42 (10.6%) NW, followed by redness of skin in 19 (4.7%) WW, 7 (1.7%) NW. Most women solve the problem by starting self-medication (180 [22.7%]). For all the variables, Chi-square test was found to be more than 0.05, and statistically significant difference was not found between the adverse effects of the cosmetic and working status of women.

Overall, 71 (39.4%) of 180 women who started self- medication had gone for a product change; in those, 67 (94.3%) women’s adverse events completely subsided after a product change. Around 74 (41.1%) of 180 women discontinued using the products until the side effects disappeared, and in those women, 63 (85.1%) women’s adverse events completely subsided.

Out of 791 women, 57 (7.2%) women (26 [6.5%] WW and 31 [7.8%] NW) consulted a dermatologist to overcome the side effects. Adverse effects from cosmetics among the study participants are given in Table 3.

| Variable | Category | Working status | Total | Chi-square | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working (396) | Nonworking (395) | ||||

| Adverse reaction experience | Yes | 163 (41.1) | 139 (35.1) | 302 (38.12) | 0.1093 |

| No | 233 (58.8) | 256 (64.8) | 489 (61.8) | ||

| Type of product | Skincare | 108 (27.2) | 87 (22.0) | 195 (24.6) | 0.136 |

| Hair care | 54 (13.6) | 48 (12.1) | 102 (12.8) | ||

| Not applicable | 234 (59.0) | 260 (65.8) | 494 (62.4) | ||

| Duration of reaction occurred | After 1 week | 98 (28.7) | 83 (21.0) | 181 (22.8) | 0.263 |

| After 1 month | 45 (11.3) | 34 (8.6) | 79 (9.9) | ||

| After 1 year | 2 (0.50) | 2 (0.50) | 4 (0.5) | ||

| Not applicable | 251 (63.3) | 276 (69.8) | 527 (66.75) | ||

| Type of the reaction | Skin reaction | 98 (24.7) | 79 (20.0) | 179 (22.3) | 0.253 |

| Systemic reaction | 25 (6.31) | 22 (5.5) | 47 (5.8) | ||

| Skin and systemic | 3 (0.75) | 1 (0.25) | 4 (0.5) | ||

| Not applicable | 270 (68.1) | 293 (74.1) | 570 (71.2) | ||

| Affected body area | Face | 86 (21.7) | 62 (15.6) | 148 (18.7) | 0.2104 |

| Eyes | 11 (2.77) | 7 (1.77) | 18 (2.27) | ||

| Hair | 37 (9.34) | 38 (9.6) | 75 (9.44) | ||

| Hand | 9 (2.27) | 9 (2.27) | 18 (2.27) | ||

| Legs | 0 | 1 (0.25) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Lips | 1 (0.25) | 4 (1.01) | 5 (0.6) | ||

| Scalp | 0 | 1 (0.25) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Lower limb | 4 (1.01) | 1 (0.25) | 5 (0.62) | ||

| Upper limb | 0 | 1 (0.25) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Nose | 2 (0.50) | 1 (0.25) | 3 (0.37) | ||

| Face, eyes | 2 (0.50) | 0 | 2 (0.25) | ||

| Head | 4 (1.01) | 7 (1.77) | 11 (1.39) | ||

| Not applicable | 240 (60.6) | 263 (66.5) | 503 (63.5) | ||

| Type of reaction on face | Increased pimples | 58 (14.6) | 42 (10.6) | 100 (12.6) | 0.136 |

| Increased facial hair | 2 (0.50) | 3 (0.7) | 5 (0.6) | ||

| Increased pimples and redness of skin | 7 (1.7) | 8 (2.02) | 15 (1.8) | ||

| Not applicable | 302 (76.2) | 325 (82.2) | 627 (79.3) | ||

| Rashes | 3 (0.75) | 4 (1.01) | 7 (0.8) | ||

| Redness of skin | 19 (4.7) | 7 (1.77) | 26 (3.25) | ||

| Sensitive skin | 5 (1.2) | 5 (1.2) | 10 (1.25) | ||

| Weeping and dermatitis | 0 | 1 (0.25) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Type of consultation adopted | Dermatologist | 26 (6.5) | 31 (7.8) | 57 (7.2) | 0.0423 |

| Pharmacist | 11 (2.7) | 15 (3.7) | 26 (3.25) | ||

| Started self-medication | 104 (26.2) | 76 (19.2) | 180 (22.7) | ||

| Beautician | 18 (4.5) | 9 (2.2) | 27 (3.4) | ||

| Not applicable | 237 (59.8) | 264 (66.8) | 501 (63.3) | ||

| Measures adopted | Product withdrawal | 28 (7.07) | 29 (7.3) | 57 (7.20) | 0.0962 |

| Product change | 59 (14.8) | 58 (14.6) | 117 (14.7) | ||

| Drug treatment | 22 (5.5) | 20 (5.06) | 42 (5.3) | ||

| Stopped using the product until adverse events disappeared | 52 (13.1) | 29 (7.34) | 81 (10.2) | ||

| Not applicable | 235 (58.5) | 259 (65.5) | 494 (62.45) | ||

| Side effects completely subside | Yes | 143 (36.1) | 109 (27.5) | 252 (31.8) | 0.013 |

| after treatment | No | 11 (2.7) | 20 (5.0) | 31 (3.8) | |

| Not applicable | 242 (61.1) | 266 (67.3) | 508 (64.25) | ||

| Duration for subside of side | Within 1–2 weeks | 60 (15.1) | 41 (10.3) | 101 (12.8) | 0.0285 |

| effect | Within 3–4 weeks | 64 (16.1) | 45 (11.3) | 109 (13.6) | |

| More than 1 month | 18 (4.5) | 21 (5.3) | 39 (5) | ||

| Not applicable | 254 (64.1) | 288 (72.9) | 542 (68.5) | ||

DISCUSSION

In the last 20 years, the cosmetics business has experienced enormous expansion, leading to the development of a wide variety of products to hydrate, nourish the skin, and treat aging signs as well as inflammation. One of the fundamental elements in this industry is innovation,17,18 leading to experimentation and increased risk for adverse effects to the users. The total number of cosmetics users in this study was 791 (98.8%); the majority of them belong to the age group between 18 and 28 years, which corresponds with the study performed by Bilal et al.9 and Getachew et al.10 This can be explained by the difference in age of the study participants. Younger women may have greater demand for cosmetic products than older people because they care more about their looks and beauty. The majority of the women used more than three products per day. This might be because of the dusty/humid condition existing in the selected study area.

Among the 791 cosmetic users, 38% experienced some sort of adverse effects. Adverse cosmetic events (ACE) were most commonly seen with skin care products, followed by hair care products. The main cause for the increase in adverse events may be attributed to the use of multiple cosmetics simultaneously, which might increase the concentration of ingredients over the safe level, which might lead to adverse events or increase the synergistic action of cosmetic products.12 Acne was the most common side effect associated with the use of cosmetics and affected about 12.6% of women. Hair and face were the most affected body site due to the use of cosmetics. The findings were similar to previous research, as the researchers also stated that the frequently reported body sites were hair and face.6,12 The number of participants who attempted to consult a dermatologist was quite less. This highlights the fact that they consider cosmetics harmless and are least bothered about the occurrence of ACEs. Participants’ low reporting of adverse events may be due to their inability to identify their problems and determine whether it was the result of the cosmetics they used.6,9,19 Women in this study had the habit of reading the label and expiry date. Through these practices, the occurrence of adverse events can be minimized or ruled out. The majority of the women (58.9%) did not follow the instruction given on the label. Consumers of cosmetics are strongly advised to adhere to some safety precautions. These include being hygienic, reading the ingredient lists on the labels, and choosing cosmetics with fewer ingredients.6,20 This study revealed that the majority of the women were not aware of the presence of heavy metal content in cosmetics (58.4%). Heavy metals are dangerous to human health; their accumulation can result in dermatitis, nausea, reproductive problems, cancer, and migraines. According to Litner et al.,21 every cosmetic product contains one or more chemical substances. Many experts are of the opinion that before a product is marketed to the general public, the manufacturer is responsible for conducting a safety evaluation of their products.16,21 Regarding patch and sensitivity tests, more than half of the women did not practice testing for allergy (73.5%) and sensitivity (78%), which is similar to the study performed by Dibaba et al. (2013).6 Sensitization tests are imperative to identify contact allergies, especially in cosmetics like hair dyes and sunscreens. Around 77.2% of women were not aware of the cosmetovigilance system or reporting adverse events. Lack of awareness regarding reporting system might be the major reason for increasing the adverse events. “Cosmetovigilance is public health surveillance on cosmetic products with a public health objective.” It can be considered a crucial element in public health activities.22 People should be educated about cosmetic use and misuse.23 To promote changes in the production, marketing, and consumption of cosmetic products by the general public, cosmetovigilance must be implemented globally.17,24 The study was based on the adverse effects that respondents self-reported from using cosmetic products. Hence, there is a chance that reports may contain inaccurate responses, and reports could also be biased by respondents. A questionnaire written in English rather than the local language may have impacted the accuracy of our study results. Only females were included in the study, though male cosmetic use is also becoming more accepted in some societies.

CONCLUSION

Cosmetic use is a universal phenomenon among women who use at least one cosmetic product on a daily basis. Face and body creams, ointments, and lotions are the most commonly used products. Respondents had experienced at least one unfavorable event due to the use of cosmetics. Face was the most affected body site of respondents. It seems that offering educational initiatives to boost self-esteem could be useful for limiting unnecessary cosmetic use. The concept of cosmetovigilance can be promoted among cosmetic distributors, users, manufacturers, and other stakeholders to reduce adverse events. It is possible to view cosmetovigilance as an important aspect of public health programs. In the near future, healthcare experts should pay closer attention to this issue.

Authors’ Contributions

All the authors contributed to the research study. Manjula Nayak: Concepts, design, definition of intellectual content, literature search, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, and manuscript review. smitha s. prabhu: concepts, design, definition of intellectual content, literature search, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, and manuscript review. Dharmagadda Sreedhar: Concepts, design, definition of intellectual content, literature search, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, and manuscript review. Pradeep M. Muragundi: Concepts, design, definition of intellectual content, literature search, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, and manuscript review. Manthan D. Janodia: Concepts, design, definition of intellectual content, literature search, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, and manuscript review., Virendra S. Ligade: Concepts, design, definition of intellectual content, literature search, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, and manuscript review.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Kasturba Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal. IEC No: 585/2020. CTRI approval was also taken for the study.

Declaration of patients consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- Cosmetics and their relation to drugs In: James S, James G, eds. Encyclopedia of pharmaceutical technology. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc; 2002. p. :649-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scott Fetzer Company In: The world book encyclopedia. Chicago: World Book Inc; 1994. p. :1075-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cosmeceuticals an emerging concept: A comprehensive review. Int J Res Pharm Chem. 2013;3:308-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cosmetic’s utilization pattern among female prospective graduates of Jimma University, Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia. Master’s thesis. Jimma University.

- [Google Scholar]

- Allergies and Cosmetics, WebMD. Available at: www.webmd.com/allergies/guide/cosmetics [Last accessed on August 2022]

- [Google Scholar]

- Cosmetics utilization pattern and related adverse reactions among female university students. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2013;4:997-1004.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Women’s Health Information Center. 2004. Washington, DC: Department of Dermatology, Goorgetanin University; Available at: http://womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/factsheet/cosmetics-your-health.pdf [Last accessed on August 2022]

- [Google Scholar]

- Fragrance technology for the dermatologist-A review and practical application. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2010;9:230-41.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmetics use-related adverse events and determinants among Jigjiga town residents, Eastern Ethiopia. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:143-53.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmetic use and its adverse events among female employees of Jimma University, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2018;28:717-24.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Contamination versus preservation of cosmetics: A review on legislation, usage, infections, and contact allergy. Contact Derm. 2009;60:70-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Adverse reactions to cosmetics and methods of testing. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:10-8. quiz 19

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Results of a cosmetovigilance survey in the Netherlands. Contact Derm. 2013;68:139.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmetic dermatitis: Current perspectives. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:533-42.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Study on awareness about adverse health effects of cosmetics among females of different age groups. J Med Sci Clin Res. 2019;7:503-10.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmetic use-related adverse events: Findings from Lay public in Malaysia. Cosmet. 2020;7:41.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmetics and their associated adverse effects: A review. J Appl Pharm Sci Res. 2019;2:1-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmetics. 2018. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/cosmetics [Last accessed on July 15 2022]

- [Google Scholar]

- A cross sectional study on assessment of cosmetics utilization and self reported adverse reactions among Wollo University, Dessie campus female students, Dessie, North East Ethiopia. Eur J Pharm Med Res. 2014;2:49-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Consumer Product Safety: Cosmetics and Safety. Health Canada. Available at: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/cps-spc/cosmet-person/cons/safety-securite-eng.php [Last accessed on August 19 2022]

- [Google Scholar]

- Cosmetic ingredients: Definitions, legal requirements, and an attempt to harmonize (Global?) characterization In: Litner K, ed. Global regulatory issues for the cosmetics industry. Vol 2. William Andrew Publishing; 2009. p. :31-53.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An observational study on adverse reactions of cosmetics: The need of practice the cosmetovigilance system in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J. 2020;28:746-53.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]