Translate this page into:

Facial Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Study of Causative Factors and Site-based Algorithm for Surgical Reconstruction

Address for correspondence: Dr. Samarth Gupta, Sawai Man Singh Medical College and Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. E-mail: guptasamarth@hotmail.com

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Background:

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) can be categorized as one of the commonly occurring skin malignancies in the world, with several variations in treatment protocols. Sun exposure has been attributed to its causality; however, other factors such as gender, age, and occupation also affect its incidence. We aimed to characterize the patient population who underwent surgical management for facial BCC at a tertiary referral hospital. Further, we have described an algorithm that may aid in surgical decision-making based on the location of the lesions on the face.

Materials and Methods:

We performed a retrospective chart review of all patients who presented with a facial BCC to our institution between 2018 and 2019. Data regarding patients’ demographic characteristics, skin phototype, average sun exposure, occupation, residence place (rural or urban), and surgical outcomes were recorded.

Results:

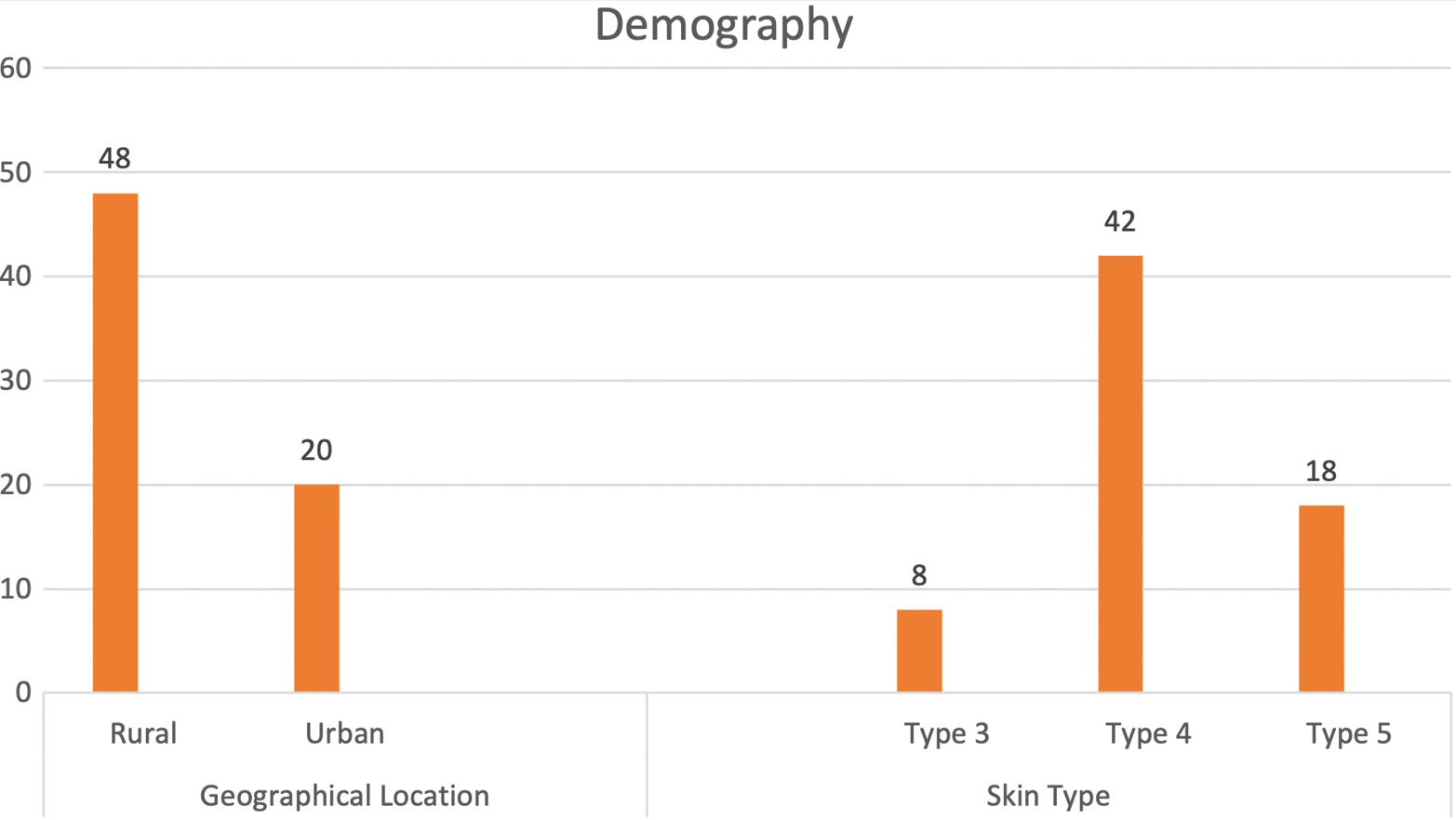

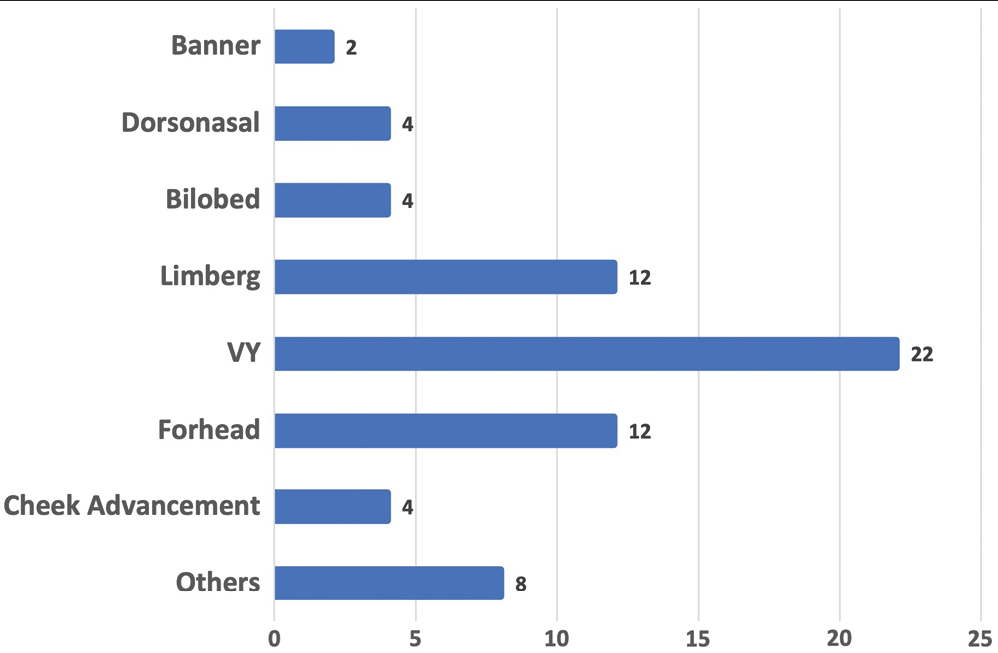

Sixty-eight patients underwent reconstructive procedures after oncologic resection of facial BCC: 41.2% were males and 58.8% were females. Forty-eight (70.6%) patients were from rural areas, and 20 patients (29.4%) from urban areas (P < 0.001). Twenty-six patients reported >2 h of sunlight exposure, 16 reported <2 h of continuous sun exposure, and 26 reported intermittent sun exposure. A significantly higher proportion of patients with facial BCC presented with a Fitzpatrick skin type 4 in comparison to types 3 and 5 (P < 0.001). The most common reconstructive technique was the V-Y advancement flap (n=22, 32.4%), followed by the forehead flap (n=12, 17.6%) and the Limberg flap (n=12, 17.6%). All the flaps were healthy post-operatively and none of them suffered from flap failure, infection, or suture line dehiscence. There was no recurrence at 1-year follow-up.

Conclusion:

This study gives a correlation between incidence of BCC and age, gender, and sun exposure in Indian population. In our experience, local flaps yield outstanding results and are the first choice for reconstruction of the face when composite defects are not present. Our algorithm aids in surgical decision-making.

Keywords

BCC

cutaneous malignancy

skin cancer

sun exposure

INTRODUCTION

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) can be categorized as one of the commonly occurring skin malignancies in the world, with several variations in treatment protocols. Sun exposure, skin type, and demographics have been attributed to play a role in the etiology and distribution of cases in different population groups. However, these factors are vaguely described in most of the previously published studies, and the association of BCC with sun exposure is still a question unanswered. In India, ultraviolet radiation is one of the causative factors for BCC as various parts in India receive radiation amounting to 10 UV Index, especially in the summer months. This is similar to countries where BCC is commonly found.

The treatment plans can be classified based on the type of speciality responsible for patient care. Therefore, from surgical excision and dermatological curettage to radiation therapy, the current literature provides a plethora of treatment options. In terms of location, size, clinical subtype, or number of lesions, surgical excision and subsequent reconstruction treatment approach are unparalleled owing to evidence in the current literature, suggesting indispensable role of surgical consultations in the recurrent cases.[12345678] Therefore, according to evidence-based clinical data and practice patterns, surgical excision is considered gold standard in the treatment of BCC. A plethora of surgical treatment options, often based on the location of the lesions on the face, are available. However, there are vague guidelines to systematically segregate the available flap reconstructive options based on different anatomical regions of defect presentation. It is of paramount importance for a surgeon to be careful while performing lesion excision as evidence suggests; recurrence is often, if not always, directly proportional to neglected margins. As the surgical excision and reconstruction go hand in hand while treating BCC, a multidimensional practical knowledge of available flap armamentarium is of utmost importance to ensure optimal functional and aesthetically acceptable outcomes.

A comprehensive review of relevant literature revealed insufficient data regarding defect-specific reconstruction option segregation. This study collates patient, etiological, and lesion characteristics and outlines an algorithm-based treatment plan.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is a retrospective observational study performed in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Sawai Man Singh Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all included patients. The purpose of the present study was to characterize the etiological factors of facial BCC, assess the association between BCC and sun exposure among other factors, and to develop a treatment algorithm to abridge the decision-making process regarding the reconstructive alternatives following oncologic resection of facial BCC. During January 2021, a retrospective chart review from September 2018 to December 2019 was accomplished of all cases presenting with a facial BCC.

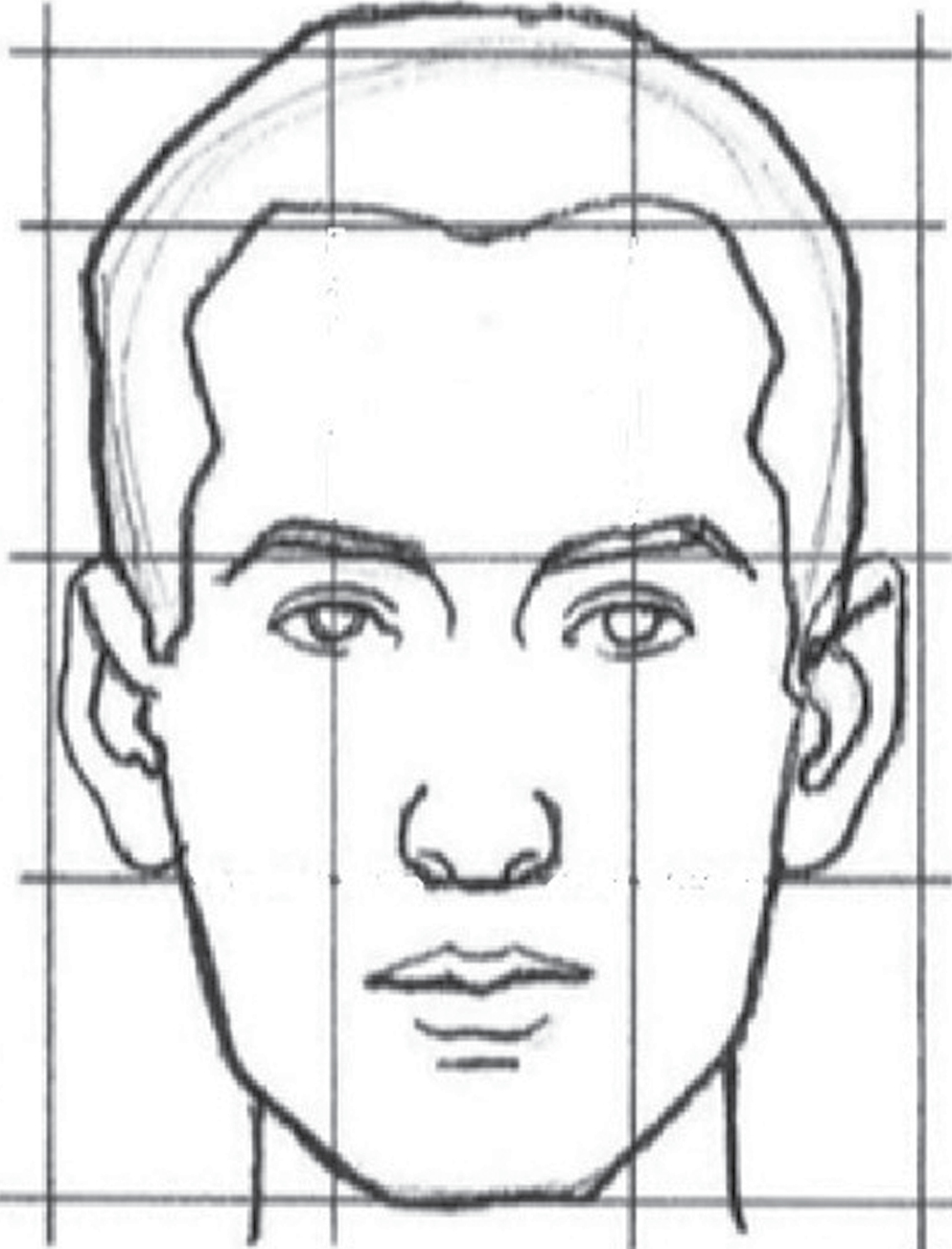

We included adult male and female patients with a confirmed diagnosis of facial BCC requiring reconstructive procedures following resection of the malignancy. Patients with other types of skin cancers, incomplete medical records, and requiring composite reconstruction of extensive defects (bone, aerodigestive tract, meningeal tissue) were excluded. The patients’ age, sex, duration of symptoms, Fitzpatrick skin type, average daily sun exposure (hours/day), occupation, residence place (rural or urban), radiation exposure history, treatment with psoralen UVA (PUVA) or narrow band UVB (NBUVB), smoking, alcohol intake, history of personal or family history of skin cancers, personal or family history of other cancers, and history of previous treatment were recorded. Clinical examination was done with data collection on various tumor variables, which included the following: size, location, number, morphological subtype, and pigmentation. The face was arbitrarily divided into three parts: upper part between the hairline and brow, central part consisted of area between the vertical mid pupillary lines, and the lateral part comprising the area lateral to this line. For descriptive purposes, the lesions were classified based on size into small (<1 cm in diameter), medium (1–2 cm in diameter), and large (>2 cm in diameter). Surgical outcome was measured by reporting flap failure, infection, suture line dehiscence, and recurrence. The patients were observed on the first follow-up at 10 days for suture removal and later at 1 year for evidence of any recurrence. Statistical analysis was performed by means of Jamovi 1.2.27.0 (Jamovi, Sydney, Australia). Values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). A χ2 goodness of fit test was used to determine if data were significantly different from the expected values, and a χ2 test for independence was used to compare variables in a contingency table and see how they relate.

RESULTS

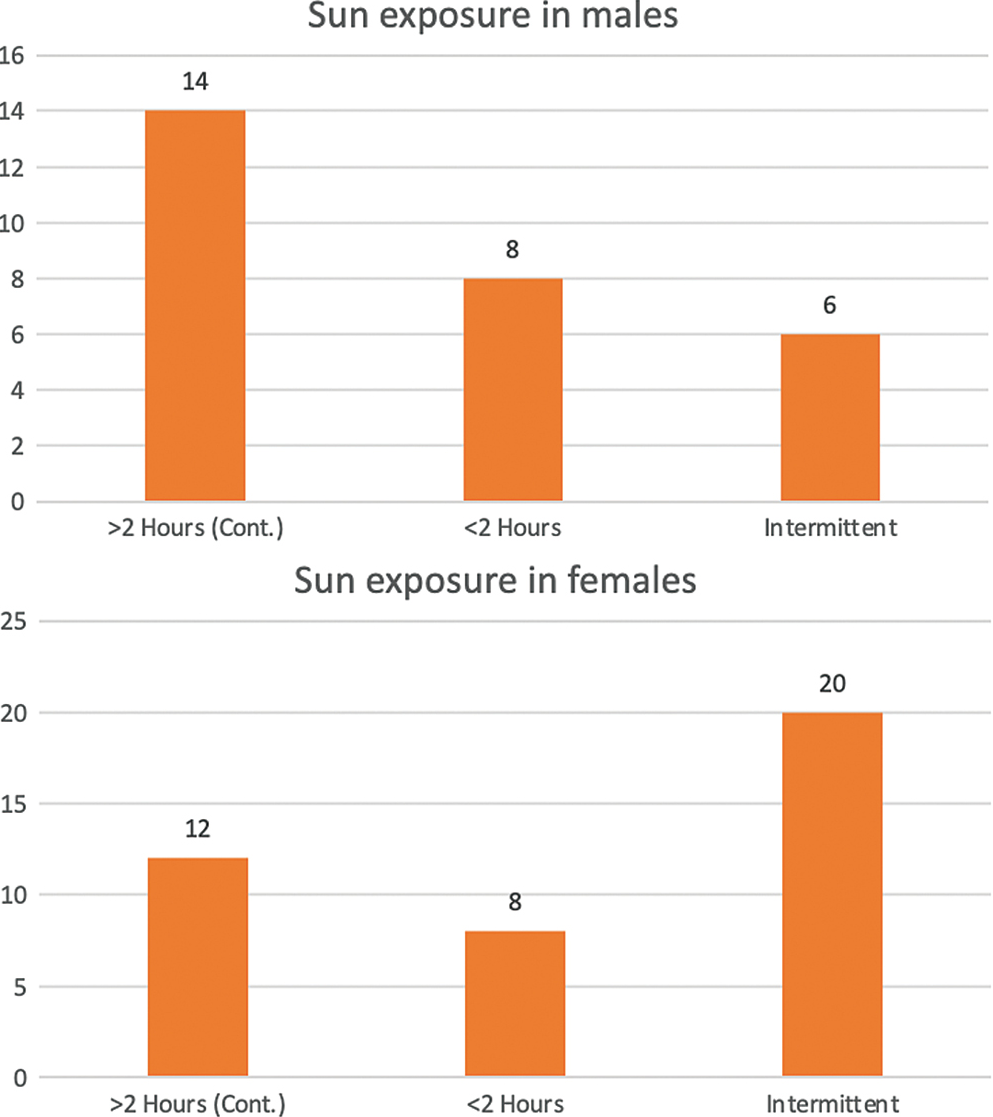

A total of 68 patients with a mean age of 48 years (range: 34–78 years) underwent reconstructive procedures after oncologic resection of facial BCC: 28 were males (41.2%) and 40 were females (58.8%). Figure 1 depicts the demographic characteristics. The average age of presentation of the male population was 48 ±4.5 and that of the female population was 54 ±6.4. A higher proportion of patients were from rural areas: 48 (70.6%) patients were from rural areas and 20 patients (29.4%) were from urban areas (P < 0.001). However, no significant difference was found regarding the geographic location (rural vs. urban) between male and female patients (P = 0.340). Twenty-six patients reported >2 h of sunlight exposure, 16 reported <2 h of continuous sun exposure, and 26 reported intermittent sun exposure, defined as multiple exposures (five or more) of at least 20 min duration. In the female population, 50% (n=20) of the patients gave history of intermittent sun exposure in contrast to males in whom continuous sun exposure of >2 h was observed in 50% (n=14). Only 21% (n=6) of the males had a history of intermittent exposure. This difference was significant when compared with females (P<0.01).

- Demographical characteristics

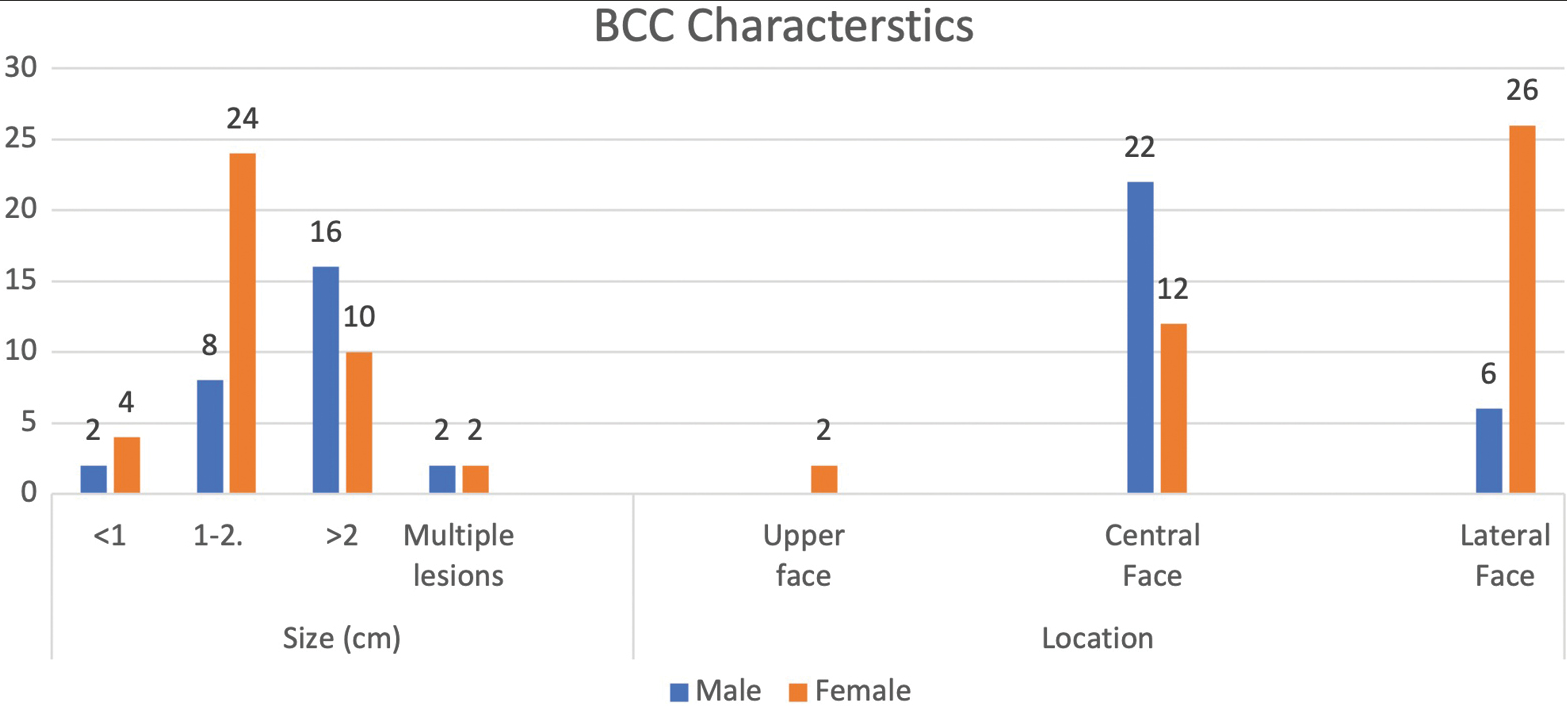

The females in our population presented with smaller lesions (1.5 ±0.6 cm) compared with the males in whom the mean size of lesions was 2.4 ±1.5. Further, the females presented earlier in the course of disease from the day of onset of the symptoms (4.3±1.5 months). The males, in contrast, presented late with a mean of 8±2.5 months from the day of onset of the symptoms, the difference being statistically significant. The central face was involved in 78.5% (n=22) of the males when compared with females in whom the lateral face was more commonly involved (65%, n=26).

The overall highest incidence of BCC was found to be in patients >40 years of age and having >2 h sun exposure, but it was observed that the majority of patients in the younger age group had history of intermittent sun exposure. Figure 2 illustrates relationship of sun exposure with age sex. Application of sunscreen was reported by only five of our patients from the urban society, whereas none of the patients from rural setup wore sunscreen on a regular basis, defined as applying cream at least once a day on at least three occasions a week.

- Sun exposure in males and females

A significantly higher proportion of patients with facial BCC presented with a Fitzpatrick skin type 4 in comparison to types 3 and 5 (P < 0.001). A significantly higher proportion of patients with facial BCC presented with a neoplastic lesion of size >1 cm in comparison to lesions ≤1 cm of size and multiple lesions (P < 0.001). No significant differences regarding size of neoplastic lesions were reported between male and female patients (P = 0.867). A significantly higher proportion of patients with facial BCC presented with neoplastic lesions in the central face in comparison to the upper face and lateral face (P < 0.001). Six of our patients were treated for recurrence; of them four were referred from dermatologists who had undergone treatment by minimal invasive procedures and two from other surgeons who underwent surgical excision. Three of these patients who developed recurrence were the mixed subtype, two were diagnosed to have infiltrative subtype, and one of them was the nodular subtype.

Three of our patients presented with multiple lesions over the face. All were excised in a single stage and have not shown any recurrence on a 1-year follow-up. Figure 3 demonstrates BCC characteristics.

- BCC characteristics

Several techniques were used for reconstruction in this series. The most common was the V-Y advancement flap (n=22, 32.4%), the forehead flap (n=12, 17.6%), and the Limberg flap (n=12, 17.6%). A significant difference was reported between the different reconstructive techniques employed for this cohort of patients (P < 0.001). Majority of the forehead flaps were elevated by the paramedian approach (n=10) in comparison to median in two patients. None of the flaps was observed to have any complications such as flap loss, infection, or suture line dehiscence. There was no recurrence in any of the patients at 1-year follow-up.

DISCUSSION

BCC is the most common skin malignancy worldwide, accounting for 65–75% of all skin cancers. Gross differences in race-specific incidence can be observed as BCC is more prevalent in Caucasians (35–40%) when compared with Asian (2–4%) and Black (1–2%) communities.[12]

In India, the incidence is relatively on the lower side in comparison to the western world, comprising <1% of all cancers. High level of protective melanin seen in the Indian skin type can be attributed to the lower incidence.[3] However, BCC prevalence can still be considered a concerning ratio given India’s large population size.[4] Recent reports suggest that skin cancer incidence in India may be on the rise, especially in a few hotspots. Ninety-five percent of these neoplasms occur in patients aged more than 40 years, although cases in childhood and congenital basal cell epitheliomas have also been reported.[567] Despite current literature on BCC prevalence suggesting it to be more common in males due to greater occupational and recreational exposure to ultraviolet radiation, we observed a significantly higher incidence in females which is in conjunction with a similar report suggesting a paradoxical increasing trend of BCC in females.[8]

UV radiation has been associated with high incidence of basal cell carcinoma as seen in countries like Australia with incidence of 884 per 100,000 and UV Index peaking up to 16. A meta-analysis of 24 studies has shown increased incidence with outdoor work, emphasizing that early life exposure of sun to be an important factor in its etiology.[9]

Indian housewives, especially rural women, perform their household duties as well as agricultural responsibilities in the open exposing them to intermittent, high intensity ultraviolet radiation. It might explain higher frequency of BCC in females in our study as intermittent rather than constant, cumulative ultraviolet radiation exposure is implicated in the pathogenesis of BCC.[10]

According to our patient data analysis, it was recorded that the majority of our patients were from rural locations, with females from such locations being more at risk of developing BCC than their urban counterparts, further supporting our claim of UVA exposure-induced BCC development in rural women. Evidence from previous studies suggests that intermittent and childhood sunlight exposure may be important for the pathogenesis of BCC, whereas continuous, lifelong sunlight exposure may be important for SCC.[1112131415] A relatively high proportion of BCCs occurs on body sites that are not routinely exposed to the sun,[1617] suggesting that exposure early in life or intermittent exposure pattern may play a greater role in the pathogenesis than simple cumulative exposure.[18] On contrary to these findings, results from our patient analysis highlight the increased incidence of BCC among individuals having >2 h sunlight exposure. Our study demonstrates that a significant higher incidence was found in patients with >2 h of exposure and those who were >40 years old when compared with patients with exposure of <2 h and <40 years age group (P<0.005). This explains that incidence increases with the duration of sun exposure along with an advancing age. The females also presented earlier in the course of disease suggesting their cosmetic concern, while males presented very late from the day of onset of symptoms.

Tseng et al.[1920] found a dose-dependent relation between arsenic levels in drinking water and the prevalence of skin cancers, which suggest that occupations with increased exposure to harmful metals and pesticides can be an important risk factor contributing to the development of skin cancers. Our study population comprised farmers and house workers who may be exposed to arsenic as arsenic is found in phosphate-based fertilizers either by accidental ingestion or through contamination of water; but further clinical and experimental studies are essential to confirm their role in pathogenesis.[2122]

The Fitzpatrick skin-type scale, which ranges from very fair (skin type I) to very dark (skin type VI), categorizes cutaneous sensitivity to ultraviolet radiation. It is based on individual’s tendency to burn and tan and is a good predictor of relative risk for BCC and cutaneous malignant melanoma (CMM) development. The most common skin type found in the Indian population is Fitzpatrick skin-type V, followed closely by type IV.[23] In our study, we have observed a significant higher incidence of BCC in type IV Fitzpatrick skin type. This is in coherence with the theory that fairer skin is more prone to devolving damage.[24] Skin type III was seen in a few participants in our study owing to the fact that its incidence is uncommon in the Indian population. The central part of the face was the most common site for BCC occurrence in our study population, suggesting that sites continuously exposed to sunlight are at increased risk of BCC conversion. Our study reports increased presentation of lesions measuring >2 and/or 1–2 cm, which have been described by Mendez and Thornton as “ high risk lesions.”[25]

Globally, the nodular subtype is the most commonly found histological variant amounting to up to half of the cases, followed by mixed type and infiltrative type. Other subtypes that occur less frequently are superficial, metatypical, infundibulocystic, and the indeterminate type. In our study, 52% (n=36) of the patients were found to have a nodular subtype followed by infiltrative type (36%, n=18) and the mixed type (20.5%, n=14), respectively.

Surgical excision with adequate skin margins has a 95% 5-year cure rate and therefore every attempt should be made to achieve negative skin margins on histopathology because primary BCCs have higher cure rates than recurrent ones. For primary BCC, we advocated the use of 3 mm skin margins and complete excision was achieved in 96.7% (60 out of 62 primary BCC cases) of the individuals.[262728] Two patients with incomplete excision were found to be have infiltrative histological subtype which is an aggressive form of BCC. Both the cases involved area surrounding the nose; both underwent revised excision assisted with frozen section to achieve negative margins. None of them was found to develop recurrence at a 1-year follow-up. Six of our patients in this study who were previously treated at other hospitals were operated for recurrence. Wide margins of over 5 mm were used in these cases to get optimal results. None of these patients developed recurrence in 1-year follow-up.

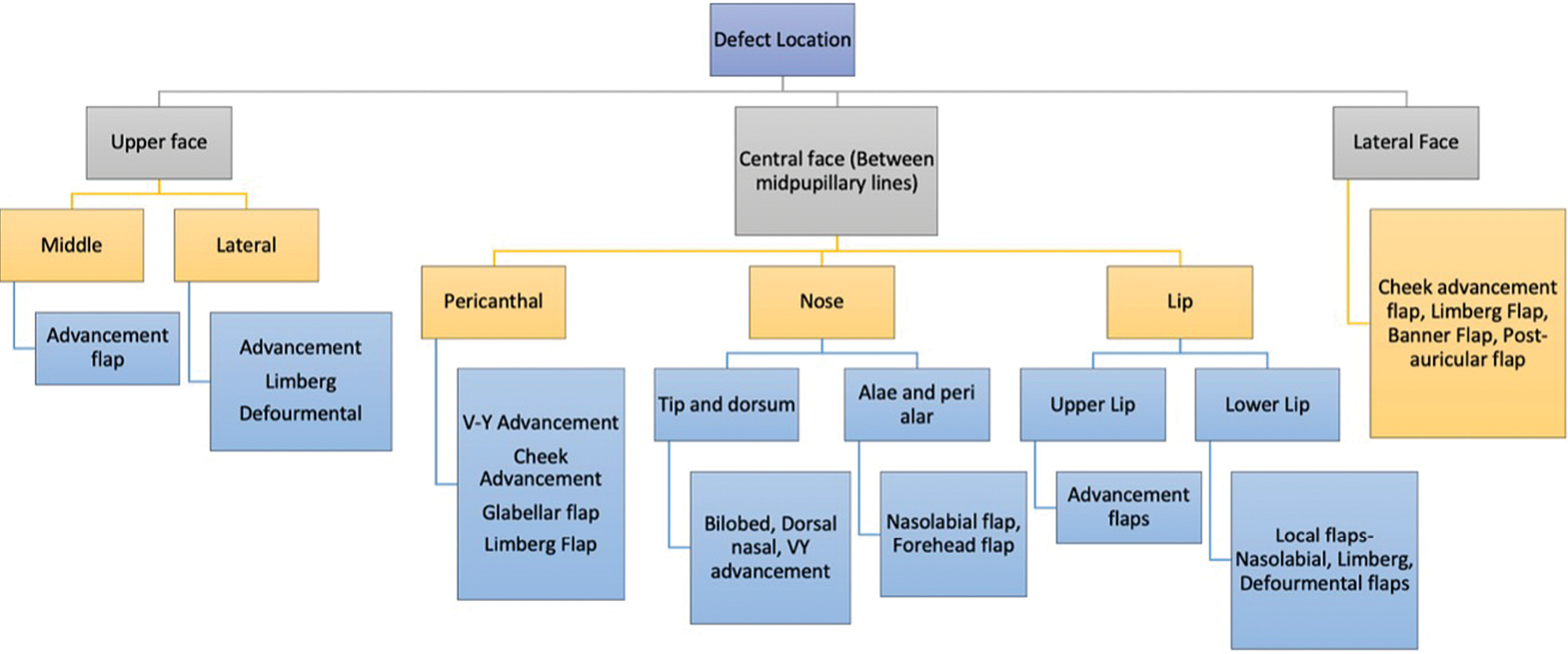

In study by Omer et al., nose was the most common site of BCC followed by cheek.[29] In our study, the central face was the most commonly involved region followed by lateral face. The females in our study presented with lateral lesions compared with central lesions on the males. Figure 4 depicts the flaps that were used in our study. The central face lesions involving nose and peri-canthal region were most commonly treated by V-Y advancement flap [Figure 5]. Other flaps that were utilized were cheek advancement flap [Figure 6], glabellar flap, dorsal nasal flap, bilobed flaps, and nasolabial flaps [Figure 7]. Most of the smaller lesions less than 5 mm were closed primarily after resection with adequate margins. Cheek advancement flap and Limberg flap [Figure 8] were commonly utilized to cover the lateral area of the face. Other less commonly used flaps were the rotation flap, cervical flap, and banner flap [Figure 9]. For reconstruction of forehead defects, “H” flap and Limberg flap were used for coverage. Based on our experience with these commonly performed flaps, we have proposed an algorithm that included all the practical surgical flap options for facial defects and simplified the decision-making process at the surgeons end. Our reconstructive algorithm is presented in Figure 10. Figure 11 illustrates the divisions used over the face.

- Flaps used to treat BCC

- V-Y advancement flap

- Cheek advancement flap

- Facial artery perforator flap from nasolabial region

- Limber flap

- Banner flap

- Reconstructive algorithm

- Divisions over face

CONCLUSION

This study has successfully described the incidence and relation of sun exposure with BCC in our region. In our experience, local flaps yield outstanding results and are the first choice for reconstruction of the face when composite defects are not present. Most defects can be best closed by means of a V-Y advancement, forehead flap, or Limberg flap; however, the choice depends on multitude of factors, the surgeon’s technical skill and experience, and understanding of the patients’ characteristics and needs. This algorithm depicts the defect-wise options which were most commonly employed in our setup with satisfactory outcome.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

None of the authors received any funds or has any financial interests to disclose for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Thesis

The present article is not part of a thesis for a degree such a Master’s or PhD degree.

Acknowledgements

(i) Conceptualization: all authors; (ii) data curation: all authors; (iii) formal analysis: all authors; (iv) funding acquisition: S. Gupta; (v) investigation: all authors; (vi) methodology: all authors; (vii) project administration: all authors; (viii) resources: all authors; (ix) software: all authors; (x) supervision: S. Gupta; (xi) validation: all authors; (xii): visualization: all authors; (xiii) writing—original draft: all authors; (xiv) writing—review and editing: all authors.

REFERENCES

- Risk and outcome analysis of 1832 consecutively excised basal cell carcinoma’s in a tertiary referral plastic surgery unit. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:2057-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgical management of skin cancers: Experience from a regional cancer centre in north India. Indian J Cancer. 2005;42:145-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Basal cell carcinoma in children: Report of 3 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:370-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Basal cell carcinoma in young adults: Not more aggressive than in older patients. Dermatology. 1999;199:119-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Basal cell carcinoma: Evaluation of clinical and histologic variables. Indian J Dermatol. 2004;49:25-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is occupational solar ultraviolet irradiation a relevant risk factor for basal cell carcinoma? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the epidemiological literature. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:612-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin in Sion, Switzerland: A case-control study. Tumori. 1999;85:435-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Case-control study of sun exposure and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Int J Cancer. 1998;77:347-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sunlight exposure, pigmentation factors, and risk of nonmelanocytic skin cancer. II. Squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:164-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sunlight exposure, pigmentary factors, and risk of nonmelanocytic skin cancer. I. Basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:157-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tanning beds, sunlamps, and risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:562-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does intermittent sun exposure cause basal cell carcinoma? A case-control study in Western Australia. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:489-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Basal cell carcinoma: Epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of the hedgehog signaling pathway in cancer: A comprehensive review. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2018;18:8-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dermatoscopy of neoplastic skin lesions: Recent advances, updates, and revisions. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects and dose response relationships of skin cancer and blackfoot disease with arsenic. Environ Health Perspect. 1977;19:109-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of skin cancer in an endemic area of chronic arsenicism in Taiwan. J Natl Cancer Inst. ;40:453-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modification of risk of arsenic-induced skin lesions by sunlight exposure, smoking, and occupational exposures in Bangladesh. Epidemiology. 2006;17:459-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Telomere length, arsenic exposure and risk of basal cell carcinoma of skin. Carcinogenesis. 2019;40:715-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick skin typing: Applications in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:93-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Actinic damage and skin cancer in albinos in Northern Tanzania: Findings in 164 patients enrolled in an outreach skin care program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:653-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current basal and squamous cell skin cancer management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142:373e-87e.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgical treatment of basal cell carcinoma: An algorithm based on the literature. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:377-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgical margin of excision in basal cell carcinoma: A systematic review of literature. Cureus. 2020;12:e9211.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the management of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:35-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Basal cell carcinoma of the head and neck region: An analysis of 171 cases. J Skin Cancer. 2012;2012:943472.

- [Google Scholar]