Translate this page into:

Photodynamic Therapy Followed by Mohs Micrographic Surgery Compared to Mohs Micrographic Surgery Alone for the Treatment of Basal Cell Carcinoma: Results of a Pilot Single-Blinded Randomised Controlled Trial

Address for correspondence: Dr. Firas Al-Niaimi, Department of Dermatology, Salford Royal Foundation Trust, Manchester, UK. E-mail: firas55@hotmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

Basal cell carcinoma is a common cutaneous malignant tumour. Surgical excision is the “gold standard” treatment for most subtypes, with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) offering the highest cure rate. Other treatment modalities used include photodynamic therapy (PDT).

Background:

We aimed to study the efficacy of combining MMS with PDT to see whether this would reduce the number of stages and final defect size when compared with MMS alone.

Materials and Methods:

Our study was a single-centre, single-blinded, randomised and controlled pilot study involving a total of 19 patients. Nine patients were randomised to pre-treatment with PDT followed by MMS of whom two withdrew; the remaining 10 patients were randomised to the MMS alone. Follow-up visits were arranged at 3 and 6 months post-surgery.

Results:

In the PDT arm, five out of the seven treated patients (71%) had their initial tumour size decreased following PDT treatment prior to MMS. The average number of stages in the PDT arm was 1.85, compared to 2.5 in the MMS arm. The average number of sections in the PDT arm was 4.2, in comparison to 5.2 in the MMS arm.

Conclusion:

Our pilot study showed a promising but limited role for PDT as an adjunct in MMS in the treatment of selected cases of basal cell carcinomas. Larger trials, preferably multi-centred are required to further examine the role of this combination therapy.

Keywords

Basal cell carcinoma

Mohs micrographic surgery

Photodynamic therapy

INTRODUCTION

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is a common malignant tumour affecting predominantly the head and neck regions in fair skin types. Although it has a very low mortality rate, it can cause significant morbidity by local tissue destruction and invasion which can lead to disfigurement.[1] Treatment modalities used include Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) and photodynamic therapy (PDT).[2] We performed a trial of the use of PDT prior to MMS in patients with confirmed BCCs. The main objective of the study was to assess whether the combination of PDT followed by MMS is superior to MMS alone in the treatment of BCC in terms of reducing both the post-MMS defect and the mean number of stages required to achieve tumour clearance.

Study protocol and method

This was a single-centre, single-blinded, randomised and controlled pilot study. The study was approved by the St Thomas’ Hospital research ethics committee and abided by the Helsinki protocol with an international randomised controlled trial number of ISRCTN03814856. The main inclusion criteria were male or female subjects older than 18 years of age with the diagnosis of BCC (except for the morphoeic, infiltrative and subtypes) greater than 1 × 1 cm2 in size and requiring treatment with MMS. The exclusion of the aggressive subtypes in our study is based on the lack of published evidence of PDT in their management. The exclusion criteria included; a photosensitive skin disorder, hypersensitivity to methyl 5-aminolevulinate, participation in another investigational drug or research study within 30 days of study enrolment, and females of child-bearing potential. All procedures were provided by the National Health service and as such no cost analysis was performed.

All patients who entered the trial had an initial screening visit. Once informed consent for participation in the study was obtained, patients were randomised to either MMS alone or PDT followed by MMS. In the arm involving MMS alone, the procedure was performed within 3 months of the baseline screening visit. The treating physicians were blinded to whether the patients underwent prior therapy with PDT or not and patients were instructed from the outset not to disclose any previous PDT participation. Subsequently, all patients were followed up a week afterwards as part of the wound care with regular follow-ups in 3 and 6 months following treatment to assess the cosmetics outcome of the procedure, any functional compromise; and to assess the appearance and symptoms of the resultant scar tissue.

In the arm involving PDT followed by MMS, two sessions of PDT treatment were applied 1 week apart within 2 months of the initial baseline screening visit with MMS being performed within 2-10 weeks following PDT treatment (allowing for the inflammation to settle). PDT involved preparing the site with topical acetone and light abrasion with curettage before application of topical methyl aminolaevulinate cream (160 mg/g; Metvix®, Photocure, Oslo, Norway) under an occlusive dressing (Tegaderm, 3M Health Care, St Paul, MN, USA) for 3 hours. This was performed by a single healthcare professional for all the involved patients who was not involved in the MMS procedures in order to ensure consistency and to eliminate any bias. After 3 hours, the dressing was removed and the cream wiped off. Each lesion was then illuminated with non-coherent red light (Aktilite CL128, Photocure, Oslo, Norway; average wavelength 631 nm, light dose 37 J/cm2, light intensity 70-100 mW/cm2). The follow-up schedule was similar to the MMS arm with visits after 3 and 6 months to ensure there were no adverse events and to assess patients’ satisfaction with the scar.

RESULTS

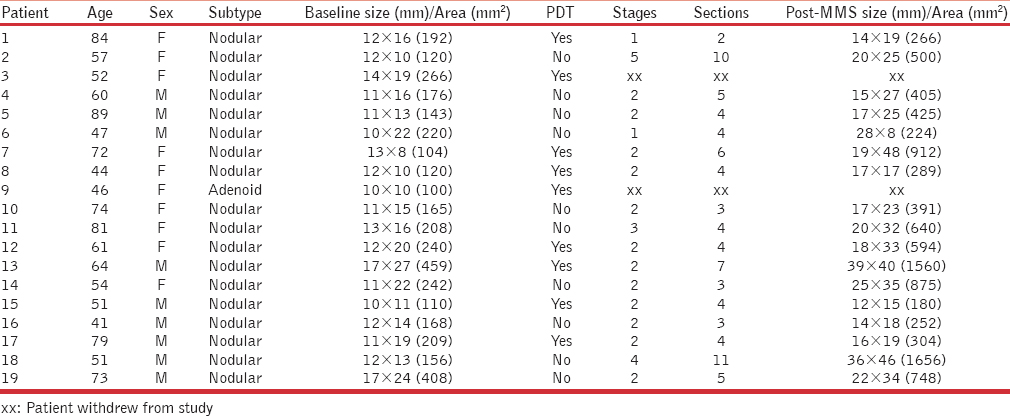

A total of 19 patients were recruited into the study. There were nine men and 10 women. The age range was 41-89 (mean age of 62). Table 1 summarises all the findings of the trial. The majority of the BCC subtypes were nodular (n = 15, 79%). The anatomical site for all tumours was facial (cheeks, nose, and forehead). A total of nine patients were randomised to the PDT followed by MMS arm. Two patients withdrew from the study; giving rise to a total of seven patients who completed treatment with PDT and MMS. The remaining 10 patients were randomised to undergo MMS only, all of whom completed the treatment. This makes a total of 17 patients who completed the treatment (89%).

Four out of the seven treated patients (71%) treated by PDT showed a reduction in tumour size and surface area prior to MMS. MMS in this group required an average number of 1.85 stages to achieve tumour clearance, compared to 2.5 in those patients who underwent MMS alone. The average number of sections in the group treated with PDT before MMS was 4.2, in comparison to 5.2 in those patients who underwent MMS alone. In the PDT arm, the mean surface area pre- and post-MMS was 204 and 586 mm2, respectively In the MMS arm the mean surface area was 201 mm2 prior to MMS and 612 mm2 afterwards. All PDT-related inflammation has settled at the time of MMS and measurements were taken immediately prior to PDT or MMS treatment and immediately post-MMS prior to surgical reconstruction.

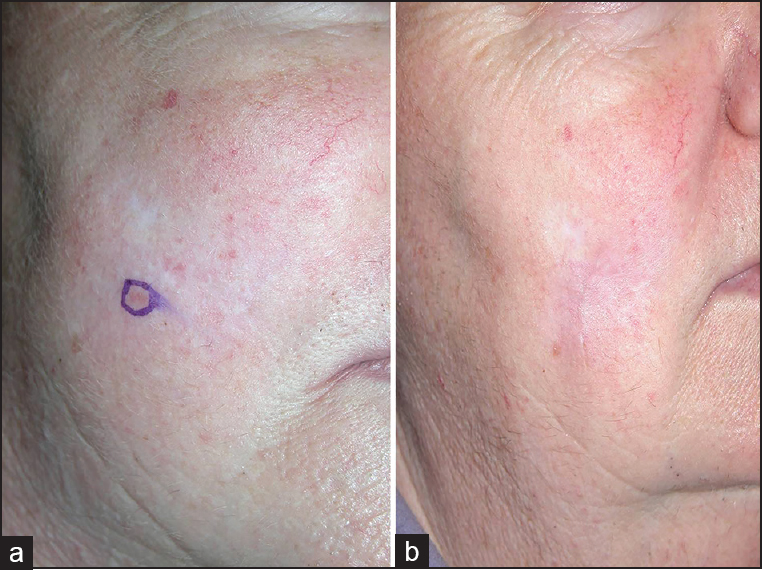

A total of two patients withdrew from the study (11%), one due to unexpected adverse reaction to the topical Metvix® cream in the PDT arm in the form of irritant dermatitis; the other patient withdrew from the study by own choice but no specific reason was given. All patients were satisfied with the resultant scar from the procedure, with no differences between the two arms. Thirteen patients (68%) completed the required follow-up at 6 months, none of whom had any clinical recurrence(s) observed as would be expected in this time frame. An image of post-PDT tumour shrinkage is provided from a patient prior to our trial in our centre [Figures 1 and 2].

- Large mixed component superficial and nodular basal cell carcinoma right on the cheek

- (a) Tumour shrinkage after two sessions of photodynamic therapy which was excised by MMS (b) Resultant scar at 3 months

DISCUSSION

Several clinical and histological subtypes of BCC exist; which include superficial, nodular, infiltrative, and morphoeic.[2] MMS was originally described in the 1930s as a way of excising difficult tumours.[3] The advantages of MMS include both accurate removal of the tumour and maximal tissue preservation. The cost effectiveness of the procedure has also been proven.[4] The overall 5-year cure rate is around 99% for primary BCCs and around 95% for recurrent BCCs and therefore MMS is considered the treatment of choice for high-risk BCCs including certain sites such as the ears, lips, nose and eyes, aggressive histological subtypes such as morphoeic, micronodular and infiltrative, size greater than 2 cm, recurrent BCCs, and BCCs with perineural invasion.[2]

Other treatment modalities for BCCs include surgical excision with predetermined margins, curettage and cautery, cryotherapy, radiotherapy, and PDT.[12] Combination therapy with MMS and other treatment modalities has been shown to be of added benefit in terms of tumour clearance and post operative defect size. In one study, MMS was combined with the immunomodulator agent imiquimod 5% cream (Aldara®).[5] Data from that trial demonstrated that pre-treatment with imiquimod cream reduced the tumour size in primary nodular BCC as well as reduction in the surgical defect size.

Topical PDT is a pharmacological treatment modality predominantly for superficial and to a lesser extent nodular BCCs[16] although BCCs often have a mixed histology. Following absorption of the applied topical photosensitizer, destruction of targeted cells and apoptosis occurs once activated by a specific light source that works through the formation of endogenous photoactive porphyrins. It is an established treatment for actinic keratoses and superficial BCCs and its main advantages are the excellent cosmesis with little or no scarring.[67]

In a relatively recent published work, PDT was used to delineate tumour margins prior to MMS for superficial and nodular BCCs and the results demonstrated a possible role for this.[8]

Topical PDT as an adjunct to MMS has been used in a series of four cases published by Kuijpers et al.[9] In their cases, PDT was used after MMS in the event of residual superficial BCC on the sections rather than continuing with MMS. This allowed for smaller wound defects and therefore better cosmesis. A follow-up for a period of up to 27 months showed no recurrences. Another study showed Metvix® PDT to be an effective therapeutic modality in BCCs difficult to treat by conventional means.[10] This included large lesions (greater or equal to 15 mm on the face or extremities and greater or equal to 20 mm on the trunk), ones in the H-zone of the face, on the ear or in any patient with a high risk of surgical complications due to bleeding abnormalities. Overall, there was a complete lesion response rate of 90% at 3 months, 84% at 12 months, and 78% at 24 months with 84% of patients considering the cosmetic outcome as good or excellent at 24 months. In one patient, PDT was used as an adjunct to MMS for a lesion measuring more than 30 mm on the temple. Following PDT, the lesion reduced in size substantially allowing for MMS to be much more limited in extent.

Our study was a pilot trial involving a relatively small number of patients and this could be a limitation. The number of patients precluded any reliable statistical analysis. Our findings did not support a conclusive benefit for PDT prior to MMS.

Our target recruitment of 20 patients was not met owing to difficulties in recruitment into the study. This may reflect the difficulties faced in recruiting patients when a single centre is involved. Another limiting factor was the number of visits required in the case of being recruited to the PDT arm as most patients preferred less hospital treatment visits. The dropout rate during the trial was relatively low (10%), though only one patient (5%) discontinued due to adverse events. More than two-thirds of the initially recruited patients completed the study with the designated periods of scheduled follow-ups (68%). Though not expected due to the overall high cure rates with MMS, no recurrences of clinically evident tumours were observed in any of the patients in both arms.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our pilot study suggests that PDT has a limited role as a pre-treatment prior to MMS in selected cases, particularly for larger superficial tumours. Larger trials, preferably multi-centred are required to provide a more detailed examination on the role of PDT as an adjunctive treatment to MMS. To our knowledge, this is the first randomised trial to assess for the efficacy and outcome of MMS combination therapy with PDT.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- British Association of Dermatologists. Guidelines for the management of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:35-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemosurgery: A microscopically controlled method of cancer excision. Arch Surg. 1941;42:279-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cost effectiveness of Mohs micrographic surgery: Review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:914-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Imiquimod 5% cream as pretreatment of Mohs micrographic surgery for nodular basal cell carcinoma in the face: A prospective randomized controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:110-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- European guidelines for topical photodynamic therapy part 1: Treatment delivery and current indications - actinic keratoses, Bowen's disease, basal cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:536-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- A follow-up study of recurrence and cosmesis in completely responding superficial and nodular basal cell carcinomas treated with methyl 5-aminolaevulinate-based photodynamic therapy alone and with prior curettage. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:467-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Photodynamic diagnosis of tumor margins using methyl aminolevulinate before Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:911-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Photodynamic therapy as adjuvant treatment of extensive basal cell carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:794-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Photodynamic therapy with topical methyl aminolaevulinate for ‘difficult-to-treat’ basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:765-72.

- [Google Scholar]