Translate this page into:

Reconstruction of Defects Following Excision of Basal Cell Carcinoma of Face: A Subunit-based Algorithm

Address for correspondence: Dr. Devi Prasad Mohapatra, Department of Plastic Surgery, Superspeciality Block, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), Pondicherry 605006, India. E-mail: devimohapatra1@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Introduction:

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is a locally invasive, slowly spreading tumor arising in the basal layer of epidermis and rarely metastasizes. Surgical excision with adequate margins is curative. Reconstruction of post-excisional defects on the face is both essential and challenging.

Clinical Cases and Methods:

A retrospective review of hospital records for patients operated for BCC of the face excluding the pinna at our institute in the last 3 years was done and a review of the literature was carried out to identify the most common principles governing the optimal reconstruction of post-excisional defects on the face. Literature search was made in Embase, Medline, and Cochrane databases in the last two decades with the filters placed for human and English language studies with the search terms (Facial Basal cell carcinoma) AND reconstruction AND (Humans[Mesh]).

Results:

Records of 32 patients with facial BCC who underwent excision and reconstruction at our hospital were identified and details were recorded. Our literature search with the terms and filters mentioned above revealed 244 studies with duplicates removed. After further hand-searching, 218 journal articles were identified, reviewed, and a reconstruction algorithm was designed based on the findings.

Discussion:

Reconstruction of post-BCC excisional defects of the face relies on an adequate understanding of the general principles of reconstruction, subunit principle of facial esthetics, flap anatomy and vascularity as well as operator experience. Complex defects need innovative solutions, multidisciplinary approaches, and newer methods of reconstruction like perforator flaps and newer techniques like supermicrosurgery.

Conclusion:

Multiple reconstructive options for post-excisional defects of the BCC over the face are available and most defects can be approached in an algorithmic manner. Further well-designed prospective research studies are needed to compare outcomes of different reconstructive options for a given defect and identify the most suitable options.

Keywords

Facial basal cell carcinoma

facial reconstruction

facial sub-unit

reconstruction algorithm

INTRODUCTION

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is a locally invasive, slowly spreading tumor arising in the basal layer of epidermis and rarely metastasizes. These are more commonly seen in elderly patients, chronic sun exposure is the most common etiology. Head and neck are frequent sites of occurrence and among these, the nose is the most common location for BCC. Although most small BCC lesions can be excised primarily, the neglected ones slowly become bigger, and post-excisional reconstruction becomes more difficult. Esthetic reconstruction becomes paramount when lesions affect the face. This study aimed to highlight the most important principles of soft-tissue reconstruction in cases of post-excisional defects of BCC involving the face and proposes an algorithmic approach toward their management.

CLINICAL CASES AND METHODS

This is a hospital record-based retrospective review of patients operated for BCC of the face at our institute from August 2016 to August 2019. Adult patients (>18 years) with histopathologically confirmed BCC over the face, patients managed surgically (excision and closure with or without flaps) and patients having a post-surgery follow-up of at least 3 months were included in the review whereas patients having lesions over the pinna and, whose follow up records were not available were excluded. The size, location, a gross and histological variant of BCC, and type of reconstruction were provided as well as demographic details of the patients were obtained. Subjective esthetic scores were collected from the patient as well as an observer not involved in surgical care; on a 5-point Likert scale (0–5, 0 being unsatisfactory and 5 being highly satisfied). Scores were collected on direct observation, from the observer as well as the patient when the patient came for follow-up in the outpatient department. A review of the literature was carried out to identify the most common techniques used for reconstruction based on size and location for defects arising from the excision of BCC. The research question we wanted to answer was “what are the most suitable reconstructive options for soft-tissue defects following excision of BCC in different aesthetic units of face?” The primary outcome measure was facial esthetics following reconstruction.

A literature search was made in Embase, Medline, and Cochrane databases with the filters placed for human and English language studies with the search terms (Facial Basal cell carcinoma) AND reconstruction AND Humans [Mesh]

The search results were further hand-searched to remove studies that did not include BCC of the face or where nonsurgical therapy had been performed. All types of studies, including letters, conference abstracts, case reports, case series, randomized control trials, and systematic reviews were included in our review. Studies that did not mention esthetic outcomes were excluded.

RESULTS

Records of 32 patients with facial BCC who underwent excision and reconstruction were identified and details were recorded in an excel sheet [Table 1]. The mean age of patients in our series was 56.7 years. Most patients (n = 26) were in the age group of 40–60 years, whereas one patient was 35 years old and 5 patients were above 60 years. Gender distribution was in our series with 23 women to 9 men. The defect size ranged from 1.3 cm × 1.3 cm to 8.5 cm × 6.5 cm with an average defect size of 11.5 cm2. Among these patients, who underwent primary reconstruction, three patients (five lesions) had their defects corrected with elliptical excision and closure, and the rest were corrected with either skin graft, local or regional flaps. None of the patients in our series had undergone reconstruction with distant flaps. Vascular complications of flap were seen in two patients. Flap tip and margin discoloration was noticed in patients where cheek advancement had been done. However, both situations were managed conservatively, and discoloration improved in 72 h. Recurrence needing revision surgery was seen after 2 years of primary excision in one patient who had undergone cheek advancement flap for lower eyelid pigmented BCC. The recurrent lesion was excised with adequate margins and closed by local tissue advancement.

| Serial no | Age | Sex | BCC type | Location (facial subunit) | Defect size (cm) | Type of reconstruction | Esthetic outcome | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 55 | f | Pigmented | Left zygomatic | 2.5 × 1.5 | WLE + Mustarde flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 2 | 60 | m | Infiltrative | Right nasal alar base + upper lip | 2.5 × 2.5 | WLE + paramedian forehead flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 3 | 40 | f | Pigmented | lateral canthus of left eye | 2 × 2 | WLE + bilobed flap + medial cheek rotation | Satisfactory | No |

| 4 | 58 | f | Ulcerative | Central forehead | 1.5 × 1.5 | WLE + Primary closure | Satisfactory | No |

| 5 | 67 | f | Pigmented, ulcerative | Nasal dorsal side wall + medial and cheek | 6 × 5 | Paramedian flap with Mustarde flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 6 | 55 | f | Ulcerative | right lower eyelid | 1.5 × 1.3 | WLE + Dufourmental flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 7 | 56 | f | Nodular | Right alar base and alar side wall | 3 × 2.5 | Nasolabial flap + right composite cartilage graft | Satisfactory | No |

| 8 | 50 | f | Pigmented | Right cheek | 3.5 × 1 | Excision + cervicofacial flap right | Satisfactory | No |

| 9 | 58 | f | Pigmented | Tip of nose | 2.2 × 2 | WLE + Riegler flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 10 | 40 | f | Ulcerative | Right lower eyelid | 4.5 × 2.5 | WLE + Mustarde flap + nasal septum chondromucosal graft | Satisfactory | No |

| 11 | 64 | m | Ulcerative | Left lateral forehead | 3 × 3 | WLE + SSG | unsatisfactory | No |

| 12 | 60 | f | Pigmented | Central forehead | 3 × 2.5 | WLE and forehead advancement flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 13 | 76 | m | Superficial | left lateral forehead | 5 × 5 | Excision and FTSG (donor site: left supraclavicular region) | Satisfactory | No |

| 14 | 45 | f | Ulcerative | Left buccal, lateral and medial cheek | 8.5 × 6.5 | WLE+FTSG | Satisfactory | No |

| 15 | 35 | f | Ulcerative | Right Ala | 2 × 2 | WLE + Nasolabial flap | unsatisfactory | No |

| 16 | 56 | f | Pigmented | Right lower eyelid | 3.5 × 5 | nLE + cheek advancement flap | Satisfactory | Yes |

| 17 | 60 | F | Superficial | Right medial cheek | 1.3 × 1.3 | WLE + primary closure | Satisfactory | No |

| Superficial | Right lateral cheek | 1.3 × 1.3 | WLE + primary closure | Satisfactory | No | |||

| Superficial | Right lateral forehead | 1.5 × 1.5 | WLE + primary closure | Satisfactory | No | |||

| 18 | 52 | m | Ulcerative | Nose tip | 2 × 2 | Excision + bilobed flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 19 | 65 | f | Nodular pigmented | Medial canthus of Left eye + left dorsal nasal wall | 4.5 × 4 | WLE + median forehead flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 20 | 50 | f | Ulcerative | tip + right alar side wall of nose | 3 × 2.5 | WLE + nasolabial flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 21 | 65 | f | Superficial | Central Forehead | 3 × 3 | WLE + bilateral advancement flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 22 | 62 | m | Pigmented | Central forehead | 4 × 3 | Bilobed flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 23 | 60 | m | Ulcerative pigmented | Right cheek | 6 × 5.5 | WLE + forehead flap + Mustarde flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 24 | 50 | f | Nodular | Left lateral canthus + lateral forehead + zygomatic region | 5 × 4.5 | WLE + Lateral forehead flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 25 | 60 | f | Ulcerative pigmented | Right medial Cheek | 5 × 3.5 | WLE + cheek transposition flap + Forehead flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 26 | 58 | f | Pigmented | Right lateral Forehead | 2 × 2 | WLE+ bilateral advancement flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 27 | 55 | f | Nodular | Right lateral upper lip + philtrum | 2.5 × 2.5 | WLE + lateral lip advancement | Satisfactory | No |

| 28 | 60 | f | Ulcerative pigmented | Right zygomatic + buccal | 5 × 3.5 | WLE + superiorly based post-auricular flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 29 | 55 | m | Ulcerative pigmented | Right Lower eyelid+ zygomatic+ medial and lateral cheek | 7 × 4 | WLE + medially based cheek transposition flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 30 | 55 | f | Ulcerative pigmented | left medial cheek | 3 × 2 | WLE + cheek advancement flap | Satisfactory | No |

| 31 | 55 | f | Ulcerative | right lateral upper lip + medial cheek | 2 × 2 | WLE + primary closure | Satisfactory | No |

| 32 | 49 | m | Ulcerative | Right dorsal side wall of Nose | 1.5 × 1.5 | WLE + glabellar flap | Satisfactory | No |

WLE = wide local excision

Our literature search with the terms and filters mentioned above revealed 244 studies with duplicates removed in MEDLINE and Embase databases No suitable study could be identified in the Cochrane database. After further hand-searching, 218 journal articles including 95 case reports, 13 review articles, and 4 letters, were identified. Articles that did not discuss surgical management of BCC, facial reconstruction, and esthetic outcomes were excluded from our review.

DISCUSSION

The goals of BCC excision are R0 resection (which means the tumor has been removed completely with margins being free on both macroscopic and microscopic evaluation). Standard margins for excision include 4–5 mm from affected margins of the lesion including induration if any. Moh’s micrographic surgery is helpful in determining resection margins, especially in esthetically critical areas like eyelids and canthi. In the absence of availability of Mohs’ micrography, the lesions in such critical areas are excised with a conservative margin of 3 mm and the defect is resurfaced initially with a full-thickness graft, which is then revised if histopathology shows residual tumor. If the margins come as clear, the patient is kept under a close follow up and in those cases, full thickness skin graft serves as an acceptable reconstruction. Although total lesion removal is the overarching goal of BCC excision, esthetic reconstruction is paramount when dealing with post-excisional defects over the face.[1]

Minimizing disfigurement by reducing displacement of facial structures during reconstruction, replacement of like tissue from same esthetic unit, restoration of function to maximum are the primary goals of reconstruction in facial soft-tissue defects.[2]

Modern principles of soft-tissue defect reconstruction entail identifying and carrying out the most suitable method of reconstruction involving the reconstructive elevator irrespective of the complexity of the defect unlike the application of simplest to complex options as per the reconstructive ladder of the past. In addition, reconstruction involves consideration for restoration of form as well as function along with esthetics. The primary recommendation to reduce the complexity of reconstruction surgery needed for facial BCC is early identification and management.[3]

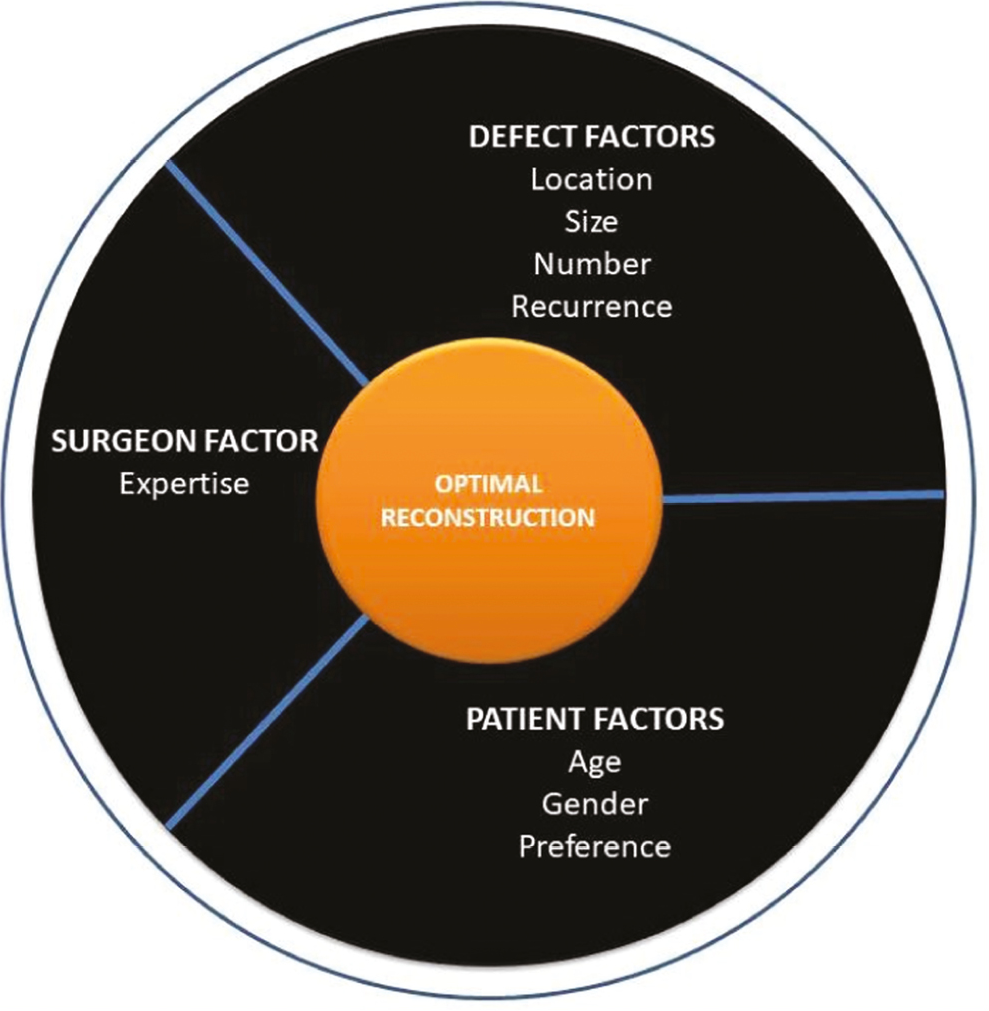

Primary closure of the post-excisional defects is done for smaller lesions with surrounding skin laxity.[4] Optimum method of reconstruction for facial defects is selected based on anatomic location, size of lesion, patient age (skin laxity), patient gender (hair-bearing skin), number of lesions, recurrent lesions, surgical skills as well as patient’s preference [Figure 1].

- Planning wheel for facial soft-tissue defect reconstruction

Allowing a defect to heal by secondary intention is preferred for very small defects. Larger defects will need flap reconstruction. Aggressive lesions of the head and neck region will need more complex procedures in form of microvascular flap reconstruction.[56]

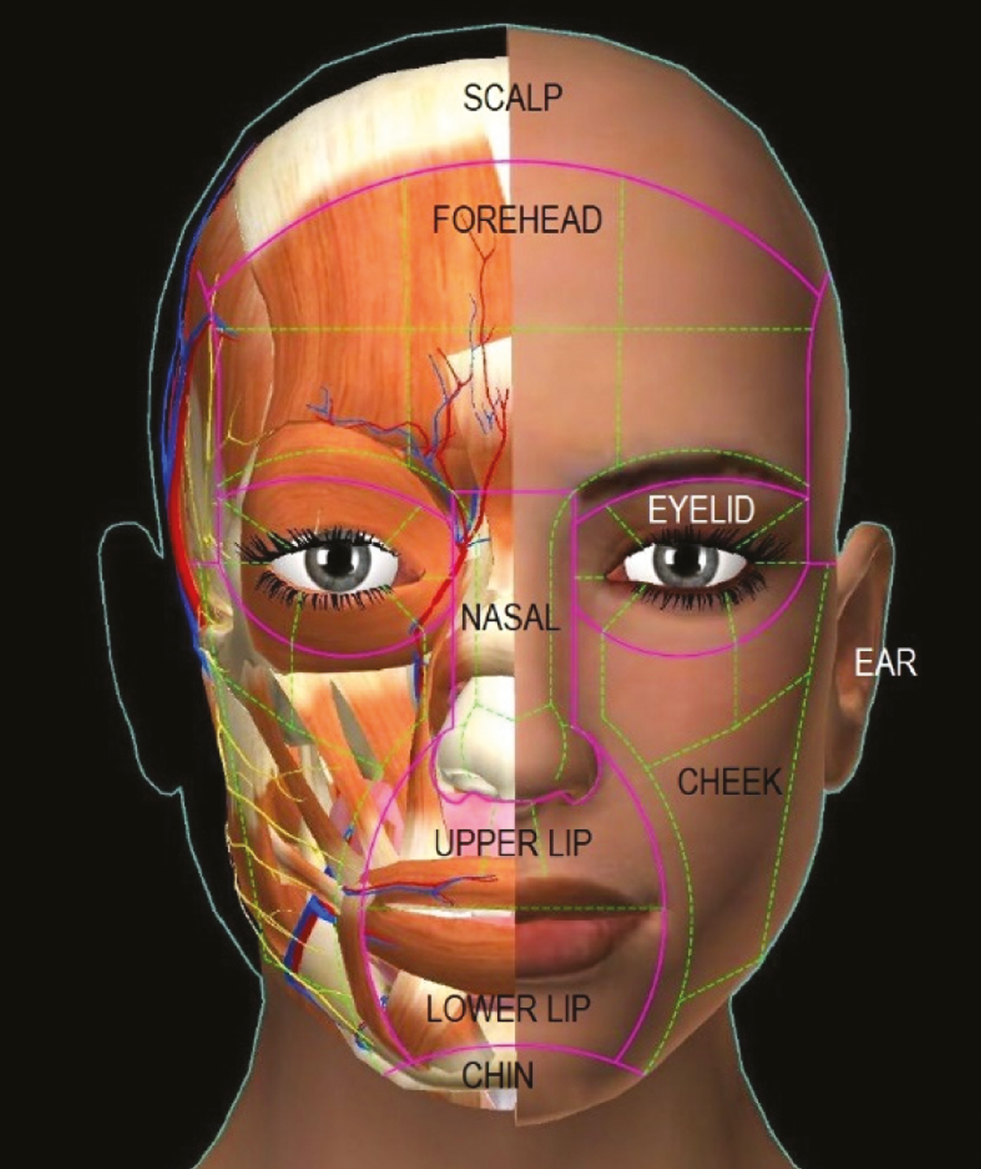

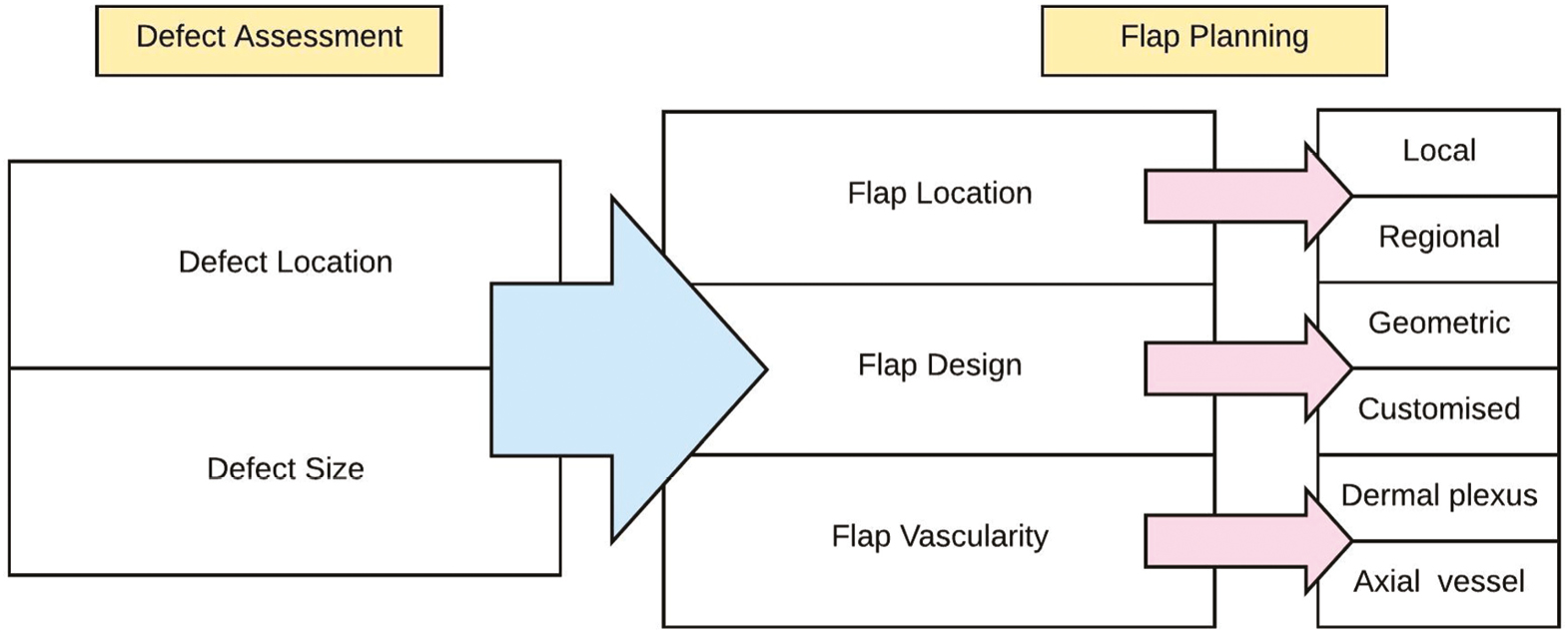

The face is divided into esthetic units [Figure 2], where the skin has similar characteristics with regard to color, thickness, amount of subcutaneous fat, texture, and presence of hair and bounded by anatomical landmarks. These units are forehead, nasal, cheek, eyelids, lips, chin, pinna, and scalp. They are fairly well-defined within their esthetic borders.[78] The borders which define these esthetic units include hairline, eyebrows, nasolabial fold, philtrum, vermillion border and labiomental fold. These esthetic units are further refined into subunits with imaginary borders for esthetic purposes. Reconstruction of a soft-tissue defect will depend on the esthetic unit where the defect lies. It is preferable to borrow tissues for reconstruction from the same esthetic unit for an optimal result. Location of the defect will also determine the vascular basis for reconstruction if a flap is being planned [Figure 3]. The size of a lesion in relation to the esthetic unit is an important factor in deciding a suitable reconstruction.

- Facial subunit diagram with esthetic and underlying anatomic components. Pink lines represent unit boundaries and green lines represent subunit boundaries

- Flow diagram for planning flap reconstruction of facial soft-tissue defects

Elderly patients are favorable candidates for primary closure as well as flap reconstruction owing to the lax nature of their skin. However, many elderly individuals have comorbidities like diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiac issues, and concurrent medications like aspirin which may interfere with outcomes. In contrast younger, individuals with tight skin may need an extensive flap procedure and undermining to mobilize adjacent skin for tension-free closure in a given defect but these flaps tend to be more robust. Younger individuals may also be more demanding with regard to cosmetic outcomes.

Patient gender is an important determinant for facial flap selection. This is because hair-bearing skin as in the beard and moustache areas needs to be taken into consideration among male patients before planning a flap reconstruction. However, in women, there is a greater liberty in selecting a flap for reconstruction.

Multiple lesions in a single facial unit are obviously difficult to treat and need more planning to achieve optimum reconstruction [Figure 4]. Lesions in multiple units of the face in the same patient need individual planning for each unit with innovations and consequently increase operating times.

- Extensive BCC of right cheek unit bordering up to right alar and upper-lip subunit in a 60-year-old man (A), resurfaced with a combination of cheek transposition flap and midline forehead flap (B). Division of forehead flap was carried out later

Recurrence of primary lesion needing excision gives a greater challenge for reconstruction as standard operations may have been carried out already in the previous setting and number of reconstructive options may become limited [Figure 5].

- Recurrent BCC in a 55-year-old man involving right alar and upper lip subunit, excised and resurfaced with midline forehead flap

Surgical skills of the operator and patient preferences determine reconstruction. More complex reconstructions are better carried out by experienced operators, whereas patients must give the final go-ahead for a specific type of reconstruction when more than one options exist for a specific defect.

Guidelines for reconstruction in different facial esthetic units are presented [Table 2]. Finer points pertaining to reconstruction in individual units is given below.

| Defect location | Defect size | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomic unit | Anatomic subunit | ||||||

| >20% (of subunit) | <20% (of subunit) | ||||||

| Forehead | Upper central | V-T or A-T advancement flaps for moderate sized defects. Still bigger defects would need specialized procedures like tissue expansion | Elliptical excision and straight-line primary closure If straight line closure is not feasible without distortion of important esthetic landmarks, geometric flaps (Limberg flap) can be done. |

||||

| Lower central | |||||||

| Upper lateral | Unilateral or bilateral advancement flaps for moderate sized defects. Larger defects would require larger transposition flaps | ||||||

| Lower lateral | |||||||

| Temporal | Cheek/ cervicofacial flap, skin graft, tissue expansion may preferred depending on the size and complexity | ||||||

| Eyebrow[9] | Upto 1/3 loss | located centrally: H flap located laterally: V-Y flap |

Primary closure | ||||

| Upto ½ loss | Located centrally: double V-Y flap Located medially/ laterally: Superficial temporal artery-based hair bearing flap |

||||||

| Complete loss | Superficial temporal artery-based hair bearing flap | ||||||

| >50% (of subunit) | 20%–50% (of subunit) | <20% (of subunit) | |||||

| Nose | Dorsum | Midline forehead flap (preferred for sidewall defects) Paramedian forehead flap (preferred for dorsum, tip, columella and ala defects) | Glabellar advancement flap (preferred for dorsum and sidewall defects on upper half) Dorsal nasal flap (Reigler flap; preferred for dorsum and sidewall on lower half and tip defects) Nasolabial islanded flap for sidewall defects in lower half |

Elliptical excision and straight-line closure. If straight line closure is not feasible without distortion of important esthetic landmarks, geometric flaps (Bilobed flap) can be done. | |||

| Sidewall | |||||||

| Tip | |||||||

| Columella | |||||||

| Ala | Nasolabial flap | ||||||

| >50% (of subunit) | 25%–50% (of subunit) | <25% (of subunit) | |||||

| Periorbital | Full thickness | Partial thickness | Full thickness | Partial thickness | Full thickness | Partial thickness | |

| Upper eyelid | Lower lid switch flap | Full thickness skin graft | Sliding tarsoconjunctival flap, Cutler-Beard flap | Full thickness skin graft | Primary closure (with or without cantholysis) | ||

| Lower eyelid | Sliding tarsoconjunctival flap with skin graft, Composite graft with cheek advancement |

Full thickness skin graft | Primary closure with lateral canthotomy and cantholysis, Tenzel flap | Primary closure with lateral canthotomy and cantholysis Tripier flap Mustarde flap |

|||

| Medial canthus | Midline forehead flap, Paramedian forehead flap | Medially based myocutaneous flap from upper lid, Glabellar advancement flap |

|||||

| Lateral canthus | Bilobed flap Cervicofacial flap |

||||||

| >50% (of unit) | 20%–50% (of unit) | <20% (of unit) | |||||

| Cheek | Suborbital | Cervicofacial flap, Skin grafts may be used in selected elderly patient with extensive/multiple lesion excision |

Geometric flaps (bilobed flap, Limberg flap) Mustarde cheek advancement flap |

Elliptical excision and straight-line closure. | |||

| Preauricular | Post auricular flap Cheek advancement flaps |

Elliptical excision and straight-line closure Geometric flaps for selected defects |

|||||

| >50% (of subunit) | 25%–50% (of subunit) | <25% (of subunit) | |||||

| Lip | Upper lip | Complex reconstruction is required. Distant flaps like deltopectoral flap, Microvascular free radial artery forearm flap (FRAFF) | Abbe lip switch flap | Can be closed primarily. If defect is full thickness, layered anatomic closure is done with advancement and alar backcut in case of upper lip | |||

| Lower lip | Estlander flap, Karapandjic flap | ||||||

| Chin | Rare site of occurrence of BCC. Small defects can be closed primarily. Larger defects need geometric flaps. | ||||||

LESIONS OF THE FOREHEAD

Forehead unit is subdivided into upper and lower regions and each region is further subdivided by two vertical lines into one central and two lateral subunits. Eyebrows are specialized landmarks of the forehead unit. Elliptical excision and closure in central subunits are oriented vertically to align along glabellar frown lines. Small to medium-sized defects of the glabellar subunit may be resurfaced with nasal root islanded flap which derives its vascular supply from the dermal plexus originating from branches of angular and supratrochlear, supraorbital arteries[10] or bilateral advancement flaps.[1011] Elliptical excision along lateral subunits may be vertical [Figure 6] or horizontal depending in skin laxity and presence of wrinkle lines. When placed horizontally, the scars should be aligned to hide in the hairline in upper part, in the skin wrinkles on the middle part and along the eyebrow margins in the lower part. The forehead skin is richly supplied on either side of midline by the dermal vascular plexus originating from frontal branch of superficial temporal artery, supra trochlear and supraorbital arteries and terminal branches of angular branch of facial artery. Owing to this vascular plexus, local advancement flaps on the forehead are generally robust and can be elevated at a supra-muscular plane. This vascularity aids in designing double hatchet flaps for small to medium size defects of the lateral forehead or even double advancement flaps [Figure 7] for medium- to large-sized defects.[12]

- Pigmented BCC over forehead lower central subunit in a 58-year-old woman managed by elliptical excision and primary closure

- Defect following excision of BCC on lateral forehead subunit in a 65-year-old woman closed with bilateral advancement flaps

LESIONS OF THE NOSE

Nasal surface is among the commonest sites for the occurrence of BCC. A planning on the type of reconstruction needed following excision can be made depending on the size of the defect in relation to the subunit it is present as well as location. Defects of the alar subunit and columellar subunit may in addition need consideration for three-dimensional reconstructions, in case of full-thickness involvement.[13] Elliptical closure is usually done in a vertical manner to hide the scar along the nasal dorsal lines. Geometric flap like bilobed flap is helpful for nasal tip defects. These are dependent on dermal vascular plexus for survival. While planning such flap, position and possible distortion of ala need to be taken into consideration. Apron flap [Figure 8] and glabellar transposition flaps are raised at supraperiosteal and supraperichondral plane for preserving the vascularity which is derived from contralateral angular branch of the facial artery.[14]

- BCC involving nasal tip subunit in a 60-year-old woman resurfaced with an apron flap

Defects involving nasal tip, supratip, and lateral nasal margins are traditionally resurfaced with nasolabial flaps [Figure 9] or may even need innovative flap designs for complex defects such as the pedicled nasal skin flap based on superficial musculoaponeurotic system.[15]

- BCC post-excisional defect involving nasal tip, supratip, and right nasal wall subunit in a 50-year-old woman resurfaced with ipsilateral superior based nasolabial flap. Flap division and inset was done at a later date

Multiple nasal dorsum lesions as seen in syndromes requiring extensive excision may be managed by an unmeshed split-thickness skin graft or a full-thickness graft covering the whole subunit.

LESIONS OF THE EYELIDS AND PERIOCULAR LESIONS

Lesions involving periocular soft tissues need meticulous planning and execution as both function and esthetics need to be restored. Well-defined algorithms have been defined for reconstruction of periocular soft-tissue defects.[16]

Smaller defects of medial canthus can be covered with islanded pedicled flaps harvested from nasal saddle or lateral nasal sidewall.[17] Larger defects are resurfaced with glabellar transposition flaps [Figure 10] or forehead flaps [Figure 11].

- Extensive post-excisional defect of the left medial upper eyelid, canthus, lower eyelid, and lateral nasal wall in a 65-year-old woman resurfaced with a midline forehead flap. Division of the forehead flap was carried out at a later date

- Smaller lesion on left lateral nasal wall resurfaced with a glabellar flap

Smaller lateral canthal defects are resurfaced with geometric flaps but bigger defects need innovative flap designs [Figure 12]. Moderate-sized defects can be covered by borrowing tissues from adjacent cheek unit. Flaps are elevated at a subcutaneous plane with attention directed toward preserving branches of facial nerve supplying the eyelids [Figure 13].

- Extensive post-excisional defect of right lateral upper lid, canthus, lower lid and upper cheek subunit in a 50-year-old woman resurfaced with a lateral forehead flap

- Smaller post-excisional defect of left lateral canthus and upper cheek subunit in a 45-year-old woman resurfaced with a pre-auricular based bilobed flap

Eyelid defects are measured in terms of width of eyelid remaining as well as thickness of eyelid involved. Full-thickness defects with loss of anterior and posterior lamella need reconstruction of both the structures and need meticulous planning [Figure 14]. Perforator flaps based on facial artery perforators can be used for reconstruction of partial thickness losses of lower eyelid.[1819] Composite grafts have been used for posterior lamella creation.[20]

- Extensive post-excisional defect involving right lower eyelid and cheek subunit in a 48-year-old woman resurfaced with a mustarde cheek advancement flap

LESIONS OF THE CHEEK

While considering defects following excision of cheek BCC, the size of the lesion and location is taken into consideration with respect to the whole cheek unit rather than individual subunits for simplicity and convenience of reconstructive planning. Cheek unit is defined by the infraorbital rim and zygomatic arch superiorly, the pinna and angle of the mandible posteriorly, the lower border of the mandible inferiorly, and the nasofacial, melolabial, and mentolabial folds medially. Elliptical excision and closure is planned in such a way that the final scar lies where possible in line with the junctions of the unit, for example, nasolabial fold [Figure 15]. In other situations, scars can be preferably placed parallel to relaxed skin tension lines. All reconstruction should take into consideration, possibility of distortion of surrounding landmarks like lips, nose, eyelids, or pinna.[21] The skin of cheek is richly supplied by dermal plexus derived from branches of facial artery.

- BCC lesion on right nasolabial fold managed with elliptical excision and primary closure

Geometric and advancement flaps in this region supported by this rich dermal plexus are raised at a subcutaneous plane. Medium-sized defects can usually be tackled by geometric flaps.[22]

To improve the reach of geometric flaps and outcomes, finer dissection to create a subcutaneous pedicle may be done. Although the reach improves, a compromise of vascularity may be seen.[23]

Retroangular flap based on retrograde blood supply from facial artery may be used in reconstruction of medium-sized defects of cheek and adjoining units although the dissection may be tedious and preoperative angiograms to delineate the facial artery are recommended by some authors.[24]

Perforator flaps based on facial artery, and superior labial artery can be used to reconstruct defects of cheek and adjoining units. Although the dissection is generally tedious and needs operator experience, the outcomes are reasonably good.[252627]

Moderate to large defects are managed with cheek advancement flaps [Figure 16]. Cheek advancement flaps can be extended to neck to convert it into a cervicofacial flap. Cervicofacial flap done for more extensive defects of cheek unit can be raised at a supraplatysmal plane in the neck or even at a subplatysmal plane with adequate care to preserve the marginal mandibular branch of facial nerve. Although geometric flaps based on axial pedicle can be planned for moderately large defects [Figure 17] of the cheek unit, strict consideration should be taken for presence of facial hair and possible redistribution to non-hair bearing areas of the cheek, particularly in men.

- BCC of left cheek suborbital unit, resurfaced with a cheek advancement

- Extensive defect of right cheek suborbital subunit in a 55-year-old man, managed with medially based cheek transposition flap. This flap is less preferable in men due to the possibility of transposition of facial hair to suborbital regions

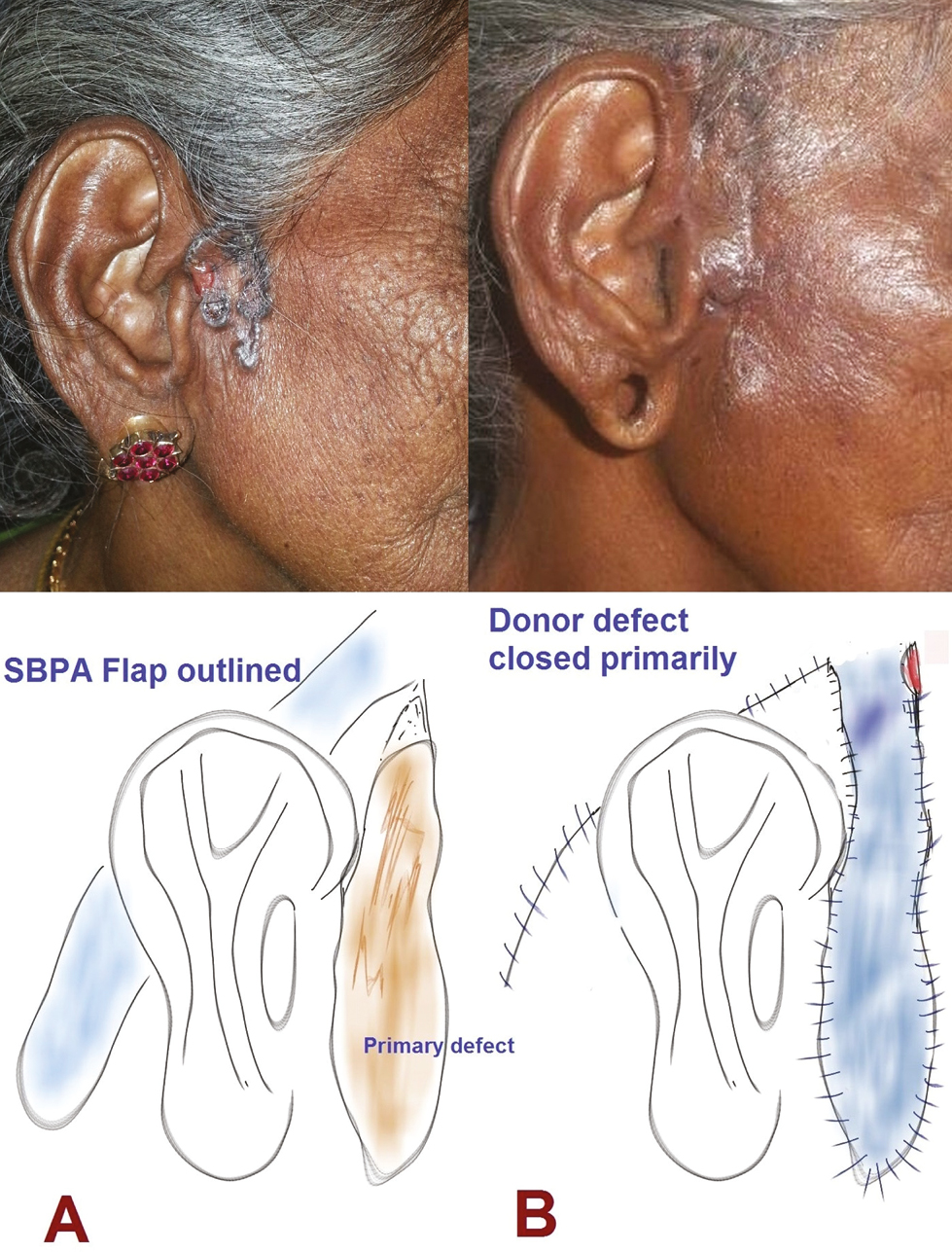

Small defects localized to preauricular subunit of the cheek can be closed primarily with the scar hidden in the sideburns. Bigger defects however need innovative designs [Figure 18] with a primary consideration of not distorting the pinna

- Lesion of preauricular subunit excised and resurfaced in a 60-year-old woman with a superiorly based post-auricular flap

LESIONS OF THE LIP

Lip is a composite structure composed of skin, muscle and mucosa with vascularity derived from superior and inferior labial arteries for upper and lower lip, respectively. RSTLs in this region are aligned in a radial pattern around the oral stoma, vertical in midline and oblique around the commissures. Small lesions should be closed with scars place along the RSTLs. Partial thickness defects of medium to large size involving the upper lip can be managed with VY advancement flaps based on dermal plexus vasculature[28] or lateral advancement flaps aided by an alar back-cut [Figure 19]. Horizontal lip shortening resulting in microstomia is a possible complication of such reconstructions.

- Post-excisional defect of the central upper lip and adjacent nasal rim in a 55-year-old woman resurfaced with lateral lip advancement

Composite defects need to be closed preferably with tissues derived from the same unit. Esthetic improvements after flap reconstruction can be obtained by fat grafting techniques.[29]

Complex defects spanning two esthetic units, for example, Ala and upper lip, need innovative flap planning and meticulous execution.[30]

LESIONS OF THE CHIN

Chin is a rare site of occurrence of BCC and principles governing excision and reconstruction remain same as other esthetic units, namely orientation of scars along the RSTLs, avoidance of distortion to landmarks like lip and preservation of vascularity to flaps if needed by elevating them at an appropriate (supra muscular) plane.

Esthetic outcomes of facial unit reconstructions can be assessed subjectively, using 2D photography or objectively by photography anthropometric methods.[3132]

Although most lesions of the face can be managed, if approached in a systematic manner, by local and regional flaps, there will be in rare instances need for more complex dissection and reconstruction techniques. This will need the involvement of a multidisciplinary team including radiologists and plastic surgeons well versed in supermicrosurgical techniques to provide the best outcomes to the patient.[33]

CONCLUSION

Reconstruction of facial defects in different facial esthetic units is essential following excision of BCC. Surgeon skills, patient’s preference, defect size and location are important determinants of esthetic outcomes. Newer modalities of reconstruction including freestyle perforator flaps give better outcomes, but operator experience is necessary. Comparative studies are lacking in comparing two or more types of flaps for reconstruction of a given esthetic unit of face. Further studies are mandated with well-designed randomized studies and an adequate number of participants, to identify an appropriate algorithm for flap reconstruction and validate the algorithm presented in this manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Miss Devangi Ramakrishnan for the help with digital artwork [Figure 2].

Financial support and sponsorship

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Facial reconstruction following Mohs micrographic surgery: A report of 622 cases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:265-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgical reconstruction of post-tumoral facial defects. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2018;59:285-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is early detection of basal cell carcinoma worthwhile? Systematic review based on the WHO criteria for screening. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:1258-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- A predictive model for primary closure lengths in Mohs surgery based on skin cancer type, dimensions, and location. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:36-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aggressive basal cell carcinoma of the head and neck: Challenges in surgical management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:3881-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reconstruction of large facial defects after delayed Mohs surgery for skin cancer. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:265-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Defects of the nose, lip, and cheek: Rebuilding the composite defect. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:887-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- A surgical algorithm for partial or total eyebrow flap reconstruction. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112:603-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The “batman flap”: A novel technique to repair a large central glabellar defect. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:477-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nasal root island flap for reconstruction of glabellar defects. Ann Plast Surg. 2015;74:34-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reconstruction of large supra-eyebrow and forehead defects using the hatchet flap principle and sparing sensory nerve branches. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;68:37-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- One-stage reconstruction of nasal defects: Evaluation of the use of modified auricular composite grafts. Facial Plast Surg. 2011;27:243-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rieger R.A.: A local flap for repair of the nasal tip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967;40:147-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- New flap for the reconstruction of the perinasal region. Facial Plast Surg. 2014;30:676-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proposal of a new classification scheme for periocular injuries. Indian J Plast Surg. 2017;50:21-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Island flaps in the repair of medial canthus: Report of 8 cases. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18576.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lower eyelid reconstruction using a nasolabial, perforator-based V-Y advancement flap: Expanding the utility of facial perforator flaps. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;82:46-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subunit reconstruction of mid-facial defects with free style facial perforator flaps. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29:1574-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prefabricated composite graft for eyelid reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg. 2015;31:534-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reconstruction of cheek defects secondary to Mohs microsurgery or wide local excision. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2017;25:443-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Letter: The “reading man” flap in facial reconstruction: Report of 12 cases. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subcutaneous pedicle Limberg flap for facial reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:949-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Indications for, and limitations of, the retroangular flap in facial reconstruction according to its vascular mapping. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;53:529-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perforator flaps of the facial artery angiosome. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66:483-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reverse superior labial artery flap in reconstruction of nose and medial cheek defects. Ann Plast Surg. 2015;74:418-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nasolabial propeller perforator flap: Anatomical study and case series. J Surg Oncol. 2018;117:1100-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcomes following V-Y advancement flap reconstruction of large upper lip defects. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2012;14:193-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Two-thirds lip defects: A new combined reconstructive technique for patients with epithelial cancer. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27:1995-2000.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nasolabial and forehead flap reconstruction of contiguous alar-upper lip defects. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:330-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of nasal reconstruction procedures results. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40:743-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Objective anthropometric analysis of eyelid reconstruction procedures. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41:52-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thin superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap and supermicrosurgery technique for face reconstruction. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:2130-3.

- [Google Scholar]