Translate this page into:

Why Do Females Use Botulinum Toxin Injections?

Address for correspondence: Dr. Carter Singh, Cosmedocs, 8-10 Harley Street, London, W1G 9PF, UK. E-mail: G777cartersingh@yahoo.co.uk

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Botulinum toxin (BT) use for enhancing the facial features has become a commonly accepted form of aesthetic intervention. This study conducted a self-report survey of female BT users in order to explore the motivating factors in its use (cost-benefit analysis).

Settings and Design:

This is a cross-sectional exploratory pilot study.

Materials and Methods:

Self-report questionnaires were administered to 41 consecutive clients attending an independent medical practice for BT injections for cosmetic purposes. All the participants were females and represented a range of age groups from the 20s to above 60s. Items in the nonstandardized questionnaire elicited questions relating to the reasons for and against BT use.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Descriptive analysis was used rather than inferential statistics, and involved ranking the responses according to the most likely reasons for using BT and disadvantages of its use.

Results:

In general, the primary motivating factor for BT use was to improve self-esteem, and the greatest disadvantage involved financial costs associated with the procedure.

Conclusions:

The main findings of this study suggest that females who use BT for aesthetic purposes are motivated by personal psychological gains (intrapersonal attributes) rather than social gains (interpersonal factors). In other words, they do not believe that having BT will equate to being treated any better by other people but would rather provide them with confidence and satisfaction regarding their self-image.

Keywords

Appearance-related behavior

botulinum toxin (BT)

self-esteem

INTRODUCTION

The pursuit of “looking good” is a universal phenomenon, common across different cultures, genders, and ethnic backgrounds. The ways in which people dress, wear make-up, and cut their hair is an expression of their desire to form a positive impression and seek approval.[1]

Psychological theories of appearance have predominantly focused upon either understanding the influences on the development of the body image including cultural socialization and personality (e.g., Cash's cognitive-behavioral model)[2] or they have considered social cognition models in an attempt to predict and explain appearance-related behaviors. However, these theories and models provide insufficient attention to the complex interplay of motivations and influences that result in whether an individual decides to either engage in an appearance-related behavior or refrain from it. Rumsey and Harcourt[3] argue that people do not necessarily behave rationally in an attempt to change their looks and may feel a pressure from society to change or from their own self-perceptions.

Consequently, exploring the motivation for appearance-change needs to incorporate methods for capturing a range of driving forces that are both positive (“to improve appearance”) and aversive (“side effects”) in nature. A simple but effective approach is to construct a cost-benefit analysis of whether to decide to undertake change. This is commonly employed as a motivational interviewing tool when seeking to understand the ambivalence that drug and alcohol dependents have about reducing their usage.[4] In our study, we explored the motivations for females who decide to use botulinum toxin (BT) for aesthetic purposes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Forty-one females who attended a clinic for BT intervention agreed to participate by completing a self-report questionnaire that was designed for this study and consisted of items relating to the following themes:

-

Benefits: What benefits do you gain from having BT?;

-

Costs: What do you not like about using BT?

Each item (e.g., pain) was rated on a Likert scale (0 = Not at all relevant, 10 = Extremely relevant).

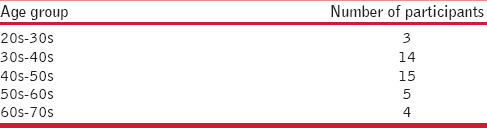

Participants represented a range of age groups [Table 1] and provided written consent for the study.

RESULTS

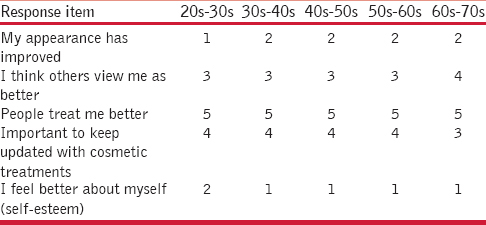

The primary reason (rank number 1) for the benefits of BT use across the age groups of 30s to 70s related to an improvement in self-esteem [Table 2]. The exception was those participants in their 20s who cited improved appearance as their main reason. The least salient reason for using BT was for social gain (people treat me better).

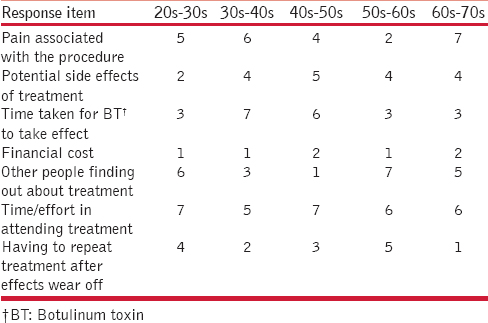

The financial cost of using BT was the main disadvantage endorsed by the majority of participants in the study [Table 3]. Other reasons such as pain associated with the procedure and the time/effort to attend the clinic were not deemed as major hindrances in its use.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study have demonstrated that the two primary reasons for BT use across the age groups are associated with improved self-esteem (number 1 reason) and with improved subjective appearance. Self-esteem has been defined as a person's perception of himself/herself as worthy and competent in comparison to others,[5] and a favorable body-image correlates with positive feelings of self-confidence.[6] It has been suggested that low self-esteem plays a crucial role in the development of emotional disorders including conditions such as depression[7] and eating disorders[8] and therefore, BT may potentially buffer against the effects of a negative self-schema and improve psychological well-being. However, this is likely to be short-lived since BT is not a permanent solution and it is unclear if repeated use is mediated by attempts to counteract a return to the previous state. Further longitudinal studies would be required to investigate the mental health impact associated with BT use for aesthetic purposes.

The findings also suggest age-related effects upon the perceptions of BT use. For example, females in their 20s and 30s rated “improved appearance” as more of a salient motivating factor than self-esteem (number 2), and those above 60 years of age were less likely to worry about what other people thought about their appearance [See Table 2]. Although these trends indicate that lifespan processes influence how people view their self-perceptions and behavior to modify their image, we are unable to generalize these findings with reliability due to the low number of participants within these age groups.

Interestingly, the idea that BT results in “being treated better by others” was the least endorsed item for wanting this intervention. This resonates with the earlier notion that the primary benefit for using BT was for self-satisfaction rather than attempting to influence the behavior of others. While societal perceptions are important (“I think others see me as better”), they do not necessarily extend to social gain.

The main disadvantage of using BT appears to be its cost; other aversive effects such as pain or possible side effects are tolerable in comparison to the benefits. However, this study was limited to BT users who chose to attend clinics. A wider understanding would need evaluation of the reasons that influence people who decide not to attend clinics for BT use.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Cognitive-behavioral perspectives on body image. In: Cash TF, Pruzinsky T, eds. A Handbook of Theory, Research and Clinical Practice. London: The Guilford Press; 2002. p. :38-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women and Children. London: Routledge; 1999. p. :25-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stability and change in low self-esteem: The role of psychosocial factors. Psychol Med. 1995;25:23-31.

- [Google Scholar]