Translate this page into:

Xanthelasma: An Update on Treatment Modalities

Address for correspondence: Dr. Zainab Laftah, King’s College Hospital, Dermatology department, Denmark Hill, London SE5 9RS, UK. E-mail: zainablaftah@gmail.com

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Xanthelasmas are localized accumulation of lipid deposits on the eyelids. Lesions are typically asymptomatic and treatment is often sought for cosmetic purposes. Unfortunately, there is paucity of strong evidence in the literature for the effective treatment of normolipidemic xanthelasmas. A literature search using the term “xanthelasma” was carried out in PubMed and Medline databases. Only articles related to treatment were considered and analyzed for their data. Commonly cited treatments include topical trichloroacetic acid, liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, and various lasers including carbon dioxide, Er:YAG, Q-switched Nd:YAG, and pulse dye laser. However, traditional surgical excision has also been used. This article reviews these currently accepted modalities of treatment.

Keywords

Normolipidemic xanthelasmas

xanthelasma

xanthelasma palpebrarum

xanthelasma treatment

INTRODUCTION

Xanthelasmas are yellowish papules and plaques caused by localized accumulation of lipid deposits commonly seen on the eyelids.

The prevalence is estimated at 4%,[1] with an incidence of 1.1% in women and 0.3% in men.[2] The age of onset can range from 15 to 73 years, although typical peaks are seen in the fourth and fifth decades. In around half of the cases, it can be associated with an underlying hyperlipidemia, and a presentation prior to the age of 40 should prompt screening to rule out underlying inherited disorders of lipoprotein metabolism.[3]

Although the exact pathogenic mechanism is not fully understood, cutaneous xanthelasma represents the deposition of fibroproliferative connective tissue associated with lipid-laden histiocytes, also known as foam cells. Histologically, these foam cells are typically found in the middle and superficial layers of the dermis in perivascular and periadnexal locations, with associated fibrosis and inflammation.[4]

Primary hyperlipidemia is caused by genetic defects in the receptors or enzymes involved in lipid metabolism. Inherited disorders of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol metabolism are typical examples that are seen in 75% of those with familial hypercholesterolemia.[2] The pathogenesis in this cohort of patients is thought to be secondary to elevated serum lipoprotein levels, which leads to extravasation of the lipoprotein through dermal capillary blood vessels and subsequent macrophage engulfment.

Secondary causes of hyperlipidemia include certain physiological states and systemic diseases. Examples include pregnancy, obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, and cholestasis.[5678] Certain medications such as estrogens, tamoxifen, prednisolone, oral retinoids, cyclosporine, and protease inhibitors can also lead to a state of hyperlipidemia.[91011]

The most common cutaneous presentation is xanthelasma palpebrarum (XP).[2] They present as soft symmetrical, bilateral, yellow, thin polygonal papules and plaques typically in the periorbital area. Other sites that may be affected include the neck, trunk, shoulders, and axillae.[2] There is no association between xanthelasmas and high-density lipoprotein or triglyceride levels.

Christoffersen et al.[12] found that independent of well-known cardiovascular risk factors, the presence of XP appeared to be a predictor of risk for myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, severe atherosclerosis, and death in the general population. Contrary to common belief, arcus senilis of the cornea is not an independent predictor of risk.[12]

Persistent XP should be distinguished from a chalazion, sebaceous hyperplasia, syringoma, nodular basal cell carcinoma, and necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG). NXGs, a form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis, are red-brown, violaceous, or yellowish cutaneous papules and nodules that evolve to form infiltrated plaques, commonly in the periorbital region. They are frequently associated with monoclonal gammopathy and other hematological malignancies.[13]

XP is typically asymptomatic and treatment is often sought for cosmetic purposes. Unfortunately, there is paucity of strong evidence in the literature for the effective treatment of XP. A literature search using the term “xanthelasma” was carried out in PubMed and Medline databases. Only articles related to treatment were considered and analyzed.

TREATMENT

XP is a benign asymptomatic lesion, not associated with any cutaneous complications; however, treatment is often sought for cosmetic reasons.

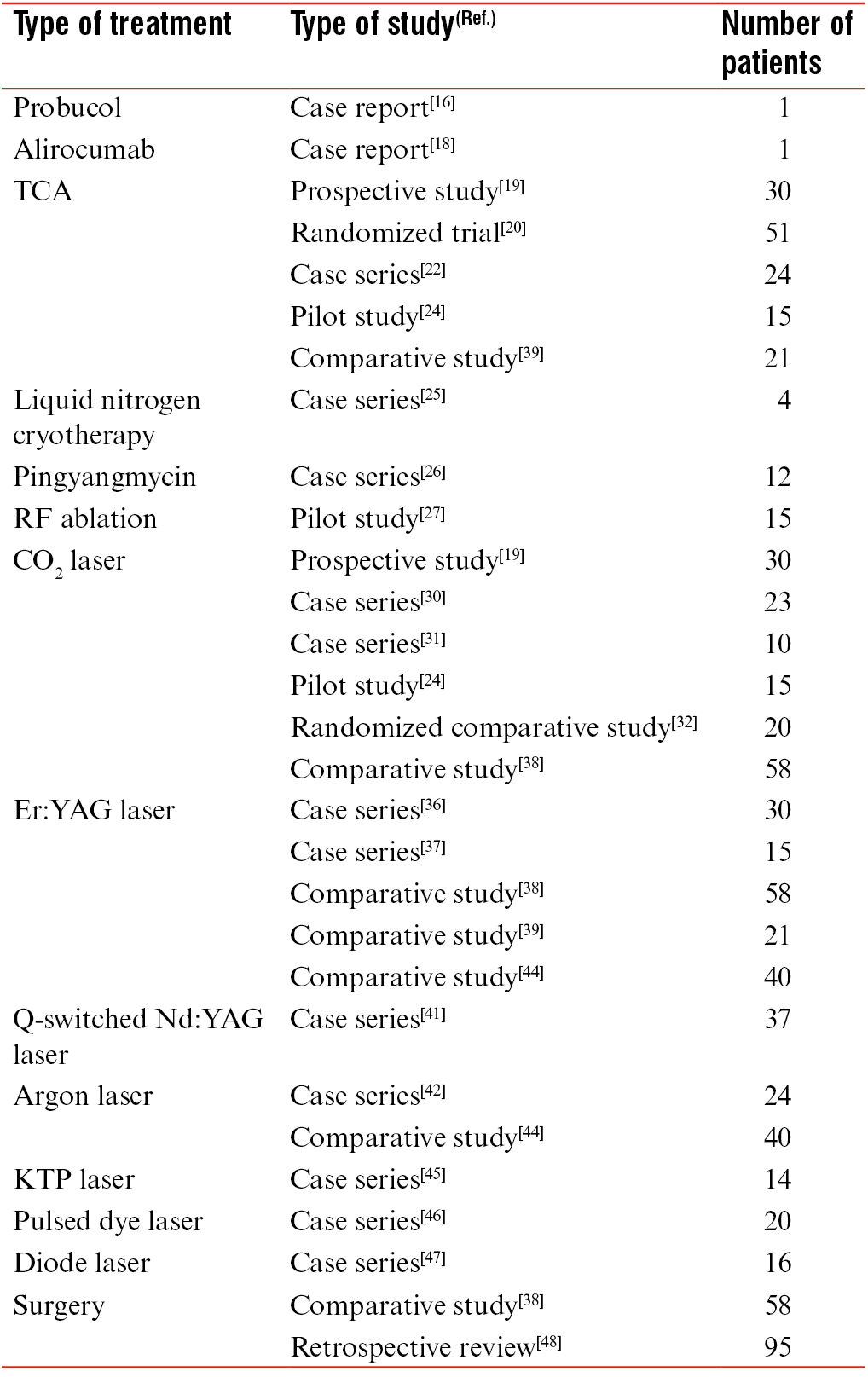

There is limited evidence in the literature for the effective treatment of normolipidemic XP. Commonly cited treatments include topical trichloroacetic acid (TCA), laser ablation, and surgical excision. There are also case reports of XP responding to systemic interleukin-1 blockade and cyclosporine-A therapy.[1014] We have reviewed the most common treatment modalities used for normolipidemic XP, their associated efficacy, particular limitations, and side effects. This is summarized in Table 1.

SYSTEMIC THERAPY

Probucol

There are reports of successful treatment using oral probucol in the literature. It is proposed that probucol, an antioxidant, acts by potentially inhibiting atherogenesis through limiting the oxidative modification of LDL cholesterol essential for foam-cell formation.[15] Miyagawa et al.[16] reported a case, of diffuse normolipemic plane xanthoma including XP, who was successfully treated with probucol. Harris et al.[17] showed 68% of xanthelasma regressed after probucol therapy.

Alirocumab

Alirocumab, a monoclonal antibody that belongs to a novel class of anticholesterol therapy through inhibition of Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), is primarily used in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia.

Civeira et al.[18] reported rapid resolution of XP after treatment with alirocumab in a middle-age man, with severe high levels of LDL cholesterol due to a familiar hypercholesterolemia. The regression of the XP was associated with lowering of LDL cholesterol concentrations.[18]

TOPICAL THERAPY

Chemical peel

TCA is a form of destructive therapy, used topically at concentrations of 50%–100%. The approach is relatively simple. It is applied in a circular manner, carefully ensuring the greatest amount of TCA is smeared at the margin of the lesion. The treatment area is then neutralized with sodium bicarbonate.

Mourad et al.[19] reviewed the efficacy and tolerability of different concentrations of TCA in the treatment of patients with XP. TCA concentrations of 35%, 50%, and 70% were tested. The authors initially degreased the skin using cotton gauze soaked in acetone. Sensitive areas, for example, the inner canthus and nasolabial folds, were protected with petrolatum ointment. TCA was then applied using a cotton-tipped applicator until solid frosting without pink background was achieved. This was usually seen within 30s to 2min. The area was then neutralized and rinsed with cold water followed by the application of a thin coat of antibiotic ointment and sunscreen.[19]

TCA 70% was found to be the most effective concentration. It was well tolerated and associated with significant clinical efficacy. This concentration required the least number of sessions in the treatment of XP. Furthermore, it was noted that TCA 70% was particularly useful in treating papular lesions whereas TCA 50% was effective for macular xanthelasma. A study by Haque and Ramesh[20] mirrored these findings. They also concluded that TCA 70% was effective in treating flat plaques; however, TCA 100% was required for papulonodular lesions.[20]

Overall, TCA therapy for XP was found to be more effective for smaller lesions, with repeated procedures resulting in pigmentation and scarring.[21] In general, postinflammatory hyper- and hypopigmentation with TCA is reported at a frequency of 9%–12.5% and 21.5%–33.4%, respectively.[2022] Some studies reported that this was dependent on the TCA concentration, whereas others did not corroborate this association.[202223] It is also important to note that if TCA is applied near the eyelid, there is a risk of scar formation and subsequent risk of ectropion development. Existing literature suggests recurrences ranging between 25% and 39%,[202122] with Goel et al.[24] describing a recurrence rate of 34.5% at 6-month follow-up in their cohort.

Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy

Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy is a simple and effective treatment option. The risk of intense swelling due to the lax skin tissue in the eyelid is the reason this treatment is generally avoided in XP. However, Labandeira et al.[25] published a case series of XP treated with very short freeze time. They reported clearance of lesions in all cases with only minor swelling associated and no recurrences during a 10-year period.[25]

The proposed mechanism of action of cryotherapy is suggested to be associated with vasoconstriction and microthrombi formation caused by cryo-induced cell death. This leads to tissue ischemia and cell death. Potential adverse effects seen with cryotherapy include edema, vesicular formation, and blister formation depending on intensity of inflammatory response. These correlate with the length of freezing and thus the temperature that the tissue reaches.[25]

Pingyangmycin

Wang et al.[26] described the treatment of XP with intralesional pingyangmycin, a broad-spectrum antitumor antibiotic. A total of 12 patients with 21 lesions received 2 treatment sessions, and in all patients except 1, the result was satisfactory. One patient experienced local recurrence 12 months after treatment. The authors described no severe associated complications.

ENERGY-BASED DEVICES

Radio-frequency ablation

Dincer et al.[27] evaluated the use of low-voltage radio-frequency (RF) ablation in the treatment of XP. Of the 15 patients who participated in the study, 9 achieved an improvement of greater than 75%. The authors concluded that this modality of treatment was effective in the treatment of XP, in particular lesions close to the eye and those that are multiple especially with indistinct borders.[27]

A comparative study by Reddy et al.[28] evaluated the efficacy of RF ablation versus TCA in the treatment of XP. Although both treatments resulted in similar improvement scores, RF ablation required fewer sessions to achieve more than 75% clearance of lesions. However, at 4 weeks posttreatment, 40% in the RF group and 15% in the TCA group had scarring, and 45% in the RF group and 30% in the TCA group had pigmentation.[28] Although fewer treatment sessions were required with RF ablation to achieve an excellent result, the treatment was associated with more complications comparatively.

Laser ablation

Laser ablation has been used to deliver targeted therapy in the treatment of XP. The mechanism of action is proposed to include (1) destruction of perivascular foam cells via thermal energy damage and (2) coagulation of dermal vessels leading to blockage of further lipid leakage into tissue, thus preventing recurrence. The use of a variety of lasers has been described in the literature, including carbon dioxide (CO2), argon, erbium (Er), and pulsed dye lasers. The CO2, neodymium-doped yttrium argon garnet (Nd:YAG), Er:YAG, and 1450-nm diode lasers all use longer wavelength of light absorbed best by cellular water, thus allowing their use in removal of epidermal lesions.[29] Argon and pulse dye lasers, on the other hand, use shorter wavelengths of light, preferentially absorbed by hemoglobin, and therefore are primarily used for vascular lesions.[29]

CO2 laser

CO2 is considered the gold-standard ablative laser. The vaporization of water within cells results in the ablation of skin layer by layer.[29] A number of studies using CO2 laser to treat patients with XP have been reported. The overall outcome was excellent, and complete initial resolution was achieved in the majority of cases. Raulin et al.[30] published a large case series of 23 patients receiving high-energy ultrapulsed CO2 laser therapy. The ultrapulsed variation enables vaporization of a thin layer of tissue whereas the pulses allow time for thermal relaxation of surrounding tissue.[31] All lesions were successfully removed, with no scarring associated and a recurrence rate of 13% at 10 months. The authors recommended treatment should be performed in the early stages of XP development to prevent recurrence.

Esmat et al.[32] compared the efficacy and safety of super-pulsed (SP) and fractional CO2 laser treatment for XP in a prospective randomized study. Bilateral XP lesions in 20 patients were treated with either a single session of ablative SP CO2 or 3–5 sessions of ablative fractional CO2 at monthly intervals. Lesions treated with SP CO2 laser showed significantly better improvements and patient satisfaction in comparison with fractional CO2 laser; however, scarring and recurrence were also higher.[32]

CO2 laser therapy has also been compared to other treatment modalities. A comparison study using 30% TCA and CO2 laser for the treatment of XP in 50 patients showed that both these modalities were effective treatments for clinically mild lesions.[24] The laser group achieved complete clearance in all patients, in contrast to the TCA group who achieved a complete clearance rate of 56%. The CO2 laser was the superior treatment option for severe lesions due to its associated coagulative effect that spreads beyond the ablative zone. Unfortunately, recurrence was a concern with both treatments, particularly for lesions that extend deep into the dermis. At 6 months, the recurrence rate with TCA was 34.8%, consistent with existing literature that reports rates ranging from 25% to 39%.[202122] The recurrence rate with CO2 at 6 months, in this study, was 16%.[24] The recurrence rates reported in the literature for CO2 are variable from no recurrence after 4 years[33] to 13% at 10 months.[30]

The efficacy of CO2 laser therapy has also been compared to higher concentrations of TCA. Mourad et al.[19] found CO2 laser ablation to be as effective as TCA 70% in the treatment of XP. Side effects reported include postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (22.2%) and hypopigmentation (33.3%).[1934]

Er:YAG laser

Er:YAG laser, a purely ablative laser, has a smaller thermal coagulation zone in comparison to CO2 laser, a classic device for skin resurfacing. The latter is associated with higher risk of scarring. The Er:YAG also has the added advantage of faster healing time, shorter duration of postlaser erythema, and postinflammatory hypo- and hyperpigmentation.[35]

Mannino et al.[36] treated 30 patients with a total of 70 xanthelasma lesions using Er:YAG laser. All lesions were effectively removed with no associated scarring or dyschromia.[36] The follow-up observation period was 12 months. Similar effective results (100% lesion removal) were also seen in a study conducted by Borelli and Kaudewitz[37] who treated 33 xanthelasma lesions with Er:YAG laser.

Another study by Lieb et al.[38] found that the wound healing was slower with CO2 compared with Er:YAG laser due to its larger associated thermal necrosis zone. The latter form of laser also had excellent results in the treatment of superficial xanthelasma. However, the authors concluded that CO2 laser was better suited for deeper lesions possibly due to its associated hemostatic property.[38]

The efficacy and complication rates of Er:YAG laser ablation in comparison to 70% TCA in the treatment for XP have also been reviewed. Güngör et al.[39] treated different XP lesions in the same patient using these two treatment modalities. They reported that both treatments have similar effectiveness and complications rates.

Q-switched Nd:YAG laser

The benefits using the 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser are not clear. Fusade[40] reported a case series of 11 patients with a total of 38 xanthelasma lesions. After a single course of treatment, they noted an excellent response (greater than 75% clearance) in six patients, a good response (51%–75% clearance) in a further two patients, and moderate (25%–50% clearance) response in the remainder.[40] However, it is important to note none of the patients achieved complete clearance.

Furthermore, these promising findings could not be replicated by Karsai et al.[41] who treated a total of 76 lesions in 37 patients with 2 sessions of Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (1064-nm and 532-nm wavelengths). Fifty-seven lesions were treated with the 1064-nm wavelength and 19 with the 532-nm wavelength. The overwhelming majority of patients showed no clearance.[41] The early disappointing results accounted for the high dropout rate; therefore, the authors advised against using Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment for XP due to poor clearance.[41]

Argon laser

Argon laser coagulation of xanthelasma lesions represents an alternative laser treatment. Basar et al.[42] treated 40 eyelids of 24 patients with XP using argon green laser. They reported that all lesions responded to therapy with a good cosmetic outcome in 85% of cases. The treatment was well tolerated with no associated complications or functionally relevant scar development.[42] Blue-green argon laser was used by Ruban et al.[43] to treat 25 patients with a total of 101 xanthelasmas. This resulted in a good cosmetic outcome in 83% of patients. Minimal scarring and slight dyschromia were seen in 13.3%, and visible scarring and marked dyschromia were evident in 3.3% of patients.[43]

The effectiveness of Er:YAG and argon lasers in the treatment of xanthelasma has also been evaluated. Abdelkader and Alashry[44] treated 40 xanthelasma lesions with argon laser and reported an excellent result in approximately 72% of cases. Small lesions less than 1cm[2] responded very well regardless of their firmness, whereas large lesions required more than one treatment session given at 2 weeks apart. However, the major disadvantage reported with argon laser photocoagulation is significant recurrence rate at 50% within the first 12–16 months after treatment,[35] with the majority occurring at the margin. Therefore, Abdelkader and Alashry[44] recommended treating the margin of the xanthelasma well, which may explain the no recurrence seen at 6 months in their study.

Potassium titanyl phosphate laser

Potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser works on the principle of selective photothermolysis. One study used KTP laser (532nm) to treat xanthelasma in 14 patients and reported an efficacy of 85.7% without side effects.[45]

Pulsed dye laser

Karsai et al.[46] described the use of 585-nm pulsed dye laser in 20 patients with XP. A total of 38 lesions were treated. The authors described promising results with majority of the patients achieving greater than 50% clearance rates.[46] Reported side effects included purpura, edema, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Diode laser

Although the 1450-nm diode laser is no longer used, the principle behind its use in the treatment of XP stemmed from data showing photothermal destruction of sebaceous glands in the mid-dermis. Park et al.[47] treated XP with 1450-nm diode laser and a cryogen cooling spray. They showed 40%–80% clearance in the majority of patients and reported minimal side effects of mild, transient postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and localized edema lasting 3–4 days.[47]

SURGERY

Traditionally, surgical excision has been used and often yields excellent cosmetic outcomes. Various surgical techniques have been advocated.

The classic blepharoplasty may be used to excise the xanthelasma in a serial staged approach, whereas Le Roux’s technique involves a modified blepharoplasty approach.[48] Recurrence, however, is common, and reported to be up to 40% and 60% following primary and secondary excision, respectively.[48]

Lee et al.[48] conducted a 4-year retrospective review of patients who received surgery for XP. Patients were classified into four grades according to the location and extent of the lesion. Ninety-five cases were reviewed, 70% of which were treated with simple excision in conjunction with blepharoplasty. The remaining 30% were treated with a combination of simple excision and local flaps or skin grafts. These were performed in patients with more advanced grades of the disease. There were no associated complications apart from postoperative scar contracture (4.2%) in patients graded III or IV.[48] Recurrence was reported in 3.1% of patients at 12 months and this was found to be irrespective of the grade.[48] The incidence of recurrence, however, is increased with incomplete excisions and has been reported in the past to be up to 40% after primary surgical excision, 60% after secondary excision, and 80% with bilateral upper and lower eyelid involvement.[49] The authors advocate that surgical excision should be the mainstay of treatment for XP lesions that involve the deep dermis or infiltrate the underlying muscle.

Other surgical techniques include a combination approach of surgery and chemical peeling. Zarem and Lorincz[50] recommend superficially excising the xanthelasma lesions using light electrodesiccation followed by the application of topical TCA.

CONCLUSION

Although XP is considered benign, they can cause significant psychological distress due to their associated cosmetic disfigurement.

They can also indicate an underlying plasma lipid disorder in approximately 50% of patients caused by a lipoprotein or apolipoprotein abnormality. Therefore, patients should be screened for underlying causes of hyperlipidemia and may require follow-up for associated morbidities.

XP rarely causes functional problems; however, treatment is usually sought for aesthetic reasons. Unfortunately, recurrence is often seen with all therapeutic modalities and currently a gold-standard long-term treatment option has yet to be established.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Xanthomas: Clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The pathogenesis and clinical significance of xanthelasma palpebrarum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:236-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dermal, subcutaneous, and tendon xanthomas: Diagnostic markers for specific lipoprotein disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:95-111.

- [Google Scholar]

- Xanthelasma palpebrarum: A review and current management principles. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:1310-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: A 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 1983;67:968-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipid abnormalities in the nephrotic syndrome: Causes, consequences, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;23:331-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hyperlipidemia in patients with primary and secondary hypothyroidism. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:860-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of postmenopausal estrogen replacement on the concentrations and metabolism of plasma lipoproteins. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1196-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of cyclosporine and prednisone on serum lipid and (apo)lipoprotein levels in renal transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;5:2073-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of oral vitamin A derivatives on lipid metabolism—What recommendations can be derived for dealing with this issue in the daily dermatological practice? J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:600-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Xanthelasmata, arcus corneae, and ischemic vascular disease and death in general population: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2011;343:d5497.

- [Google Scholar]

- Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: A review of 17 cases with emphasis on clinical and pathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:279-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of antihypertensive therapy on serum lipids. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:133-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of probucol on macrophages, leading to regression of xanthomas and atheromatous vascular lesions. Am J Cardiol. 1988;62:31B-6B.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful treatment of diffuse normolipemic plane xanthoma with probucol. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:148-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term oral administration of probucol (4,4’-(isopropylidenedithio) bis(2,6-di-t-butylphenol)) (DH-581) in the management of hypercholesterolemia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1974;22:167-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid resolution of xanthelasmas after treatment with alirocumab. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10:1259-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of efficacy and tolerability of different concentrations of trichloroacetic acid vs. carbon dioxide laser in treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14:209-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of three different strengths of trichloroacetic acid in xanthelasma palpebrarum. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17:48-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of trichloroacetic acid (95%) in the management of xanthelasma palpebrarum. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:845-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of eyelid xanthelasma with 70% trichloroacetic acid. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:280-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- A prospective study comparing ultrapulse CO2 laser and trichloroacetic acid in treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14:130-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tolerability and effectiveness of liquid nitrogen spray cryotherapy with very short freeze times in the treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:346-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum with intralesional pingyangmycin. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:368-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of low-voltage radiofrequency in the treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum: A pilot study of 15 cases. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1973-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative study to evaluate the efficacy of radiofrequency ablation versus trichloroacetic acid in the treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2016;9:236-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lasers in dermatology and medicine. London: Springer-Verlag; 2012.

- Xanthelasma palpebrarum: Treatment with the ultrapulsed CO2 laser. Lasers Surg Med. 1999;24:122-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrapulse carbon dioxide laser ablation of xanthelasma palpebrarum: A case series. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:46-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fractional CO2 laser is an effective therapeutic modality for xanthelasma palpebrarum: A randomized clinical trial. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1349-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum with the carbon dioxide laser. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1987;13:149-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- The use of CO2 laser for the treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum. Ann Plast Surg. 1993;31:504-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulsed erbium:YAG laser ablation in cutaneous surgery. Lasers Surg Med. 1996;19:324-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of Erbium:YAG laser in the treatment of palpebral xanthelasmas. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2001;32:129-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Xanthelasma palpebrarum: Treatment with the erbium:YAG laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;29:260-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- [CO2 and erbium YAG laser in eyelid surgery. A comparison] Ophthalmologe. 2000;97:835-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Erbium: YAG laser ablation versus 70% trichloroacetıc acid application in the treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25:290-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum by 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser: A study of 11 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:84-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser an effective approach to treat xanthelasma palpebrarum? Results from a clinical study of 76 cases. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1962-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum with argon laser photocoagulation. Argon laser and xanthelasma palpebrarum. Int Ophthalmol. 2004;25:9-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Argon laser versus erbium:YAG laser in the treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2015;29:116-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- [KTP laser coagulation for xanthelasma palpebrarum] J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:775-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum using a pulsed dye laser: A prospective clinical trial in 38 cases. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:610-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Xanthelasma palpebrarum treatment with a 1,450-nm-diode laser. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:791-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcomes of surgical management of xanthelasma palpebrarum. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:380-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Xanthelasma: Follow-up on results after surgical excision. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:535-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benign growths and generalized skin disorders. In: Grabb WC, Smith JW, eds. Plastic surgery: A concise guide to clinical practice (2nd). Boston: Little Brown; 1973. (chapter 28)

- [Google Scholar]