Translate this page into:

Efficacy and safety of intralesional Candida albicans antigen versus intralesional mumps, measles, rubella vaccine in the treatment of multiple cutaneous warts: A double-blinded randomized controlled trial

*Corresponding author: Satyaki Ganguly, Department of Dermatology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India. satyakiganguly@yahoo.co.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Rahim JS, Ganguly S. Efficacy and safety of intralesional Candida albicans antigen versus intralesional mumps, measles, rubella vaccine in the treatment of multiple cutaneous warts: A double-blinded randomized controlled trial. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. doi: 10.25259/JCAS_27_2024

Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of intralesional C. albicans antigen with intralesional MMR vaccine in the treatment of multiple cutaneous warts in patients aged above 12 years.

Material and Methods

This was a double-blinded randomized control trial on sixty patients with multiple cutaneous warts. Treatment group 1 received intralesional C. albicans antigen and treatment group 2 received intralesional MMR vaccine. Each patient was given a total of 0.3 mL of antigen divided into the two largest warts at week 0, 2, and 4 and followed up at week 8. Efficacy was assessed by complete response rates, distal response rates, and response rates of injected warts. Safety was assessed by the rate of adverse events occurring with either of the treatment modalities.

Results

Out of the sixty patients, 53 patients completed the study. The complete therapeutic response rate was 37.5% and 34.48% in treatment groups 1 and 2, respectively. The mean time taken to achieve complete clearance of warts was 7.33 ± 2.000 weeks and 7.2 ± 1.687 weeks, respectively. Treatment group 1 showed a significantly higher rate of side effects compared to treatment group 2.

Conclusion

Intralesional immunotherapy with Candida and MMR both showed similar efficacy, and MMR was found to be relatively safer than C. albicans antigen.

Keywords

Multiple warts

Intralesional immunotherapy

Candida

MMR

INTRODUCTION

Cutaneous warts are a common benign presentation of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection of keratinocytes. Traditional destructive modes of treatment such as topical salicylic acid, topical 5 fluorouracil, curettage, cryotherapy, light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation (LASER), and electrosurgery have several side effects, including irritant and allergic contact dermatitis, dyspigmentation, pain, blistering, scarring, and underlying tissue damage. Immunotherapy is beneficial for patients with multiple, recurrent, recalcitrant warts and warts in difficult-to-treat areas such as periungual areas and palmoplantar surfaces. Furthermore, these are relatively easy to use, non-destructive, and have lesser side effects and recurrence rates.

Immunotherapy is a type of biological therapy that uses substances to stimulate or suppress the immune system to help the body combat cancer, infection, and other diseases.1 The principle of this therapy for warts is to deliver an antigen, either intralesionally or systemically, to produce an immune response resulting in clearance of the wart. Immunotherapy acts by stimulating Th1 responses and inhibiting Th2 responses. Immunotherapy is also proposed to downregulate the gene transcription of HPV through stimulation of tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1.2 Many immunotherapeutic agents such as Candida albicans antigen, mumps, measles, rubella (MMR) vaccine, Mycobacterial antigens (purified protein derivative, bacille Calmette-Guérin, Mycobacterium w vaccine), Trichophyton antigen, vitamin D3, and IFNs have been used for intralesional therapy. The efficacy of these agents varied widely from 26.5% to 93%, with good clearance rates (23.3– 95.2%) even in pediatric population also.3 Older individuals (above 40 years) tend to respond less to immunotherapy, probably due to their weaker immune responses.4

Candida antigen was the first antigen to be studied for immunotherapy of warts in 1979 by Harada.5 It involved intralesional injection of a killed yeast protein.5 Immunotherapy with C. albicans antigen should be effective considering the high prevalence of Candida infection in the general population.6

MMR is a live-attenuated vaccine commonly used for intralesional immunotherapy of warts nowadays. Numerous studies on intralesional MMR conducted in India have reported good efficacy with the antigen. However, there are only a few studies on intralesional C. albicans for warts in India. Studies comparing intralesional C. albicans with MMR are few. Therefore, we chose to compare the efficacy and safety of intralesional MMR with intralesional C. albicans.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design

The study was a double-blinded randomized controlled superiority trial (parallel group design) conducted in a tertiary care center from November 2020 to December 2021 after obtaining permission from the institute ethics committee (AIIMSRPR/IEC/2020/501). The Clinical Trials Registry – India (CTRI) trial registration number is CTRI/2020/06/026098.

Sample size calculation

According to the study by Nofal and Nofal, the 7 cure rate in the MMR group was 84.6%, and in the study by Signore,8 the cure rate in the C. albicans antigen group was 51%. Based on this data and considering type 1 error as 5% and type 2 error as 20%, the sample size was calculated to be 27 patients in each group. Nevertheless, to compensate for probable dropouts, considering a 10% loss to follow-up, the sample size was increased to a minimum of 30 patients in each group. We recruited 60 patients for this study.

Inclusion criteria

Patients aged above 12 years with multiple cutaneous extragenital warts (more than three warts) who gave consent and assent to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with uncontrolled urticaria, uncontrolled asthma, known severe hypersensitivity to C. albicans antigen, active candidiasis, acute febrile illness, history of meningitis or convulsions, diabetes, post-splenectomy patients, lactating ladies, those receiving concomitant other treatments for warts, and patients with only oral mucosal, genital, and plane warts were not included in the study. MMR is contraindicated in patients with high fever or other signs of serious disease, pregnancy, people with a history of anaphylactic reaction to neomycin, gelatin or other components of the vaccine, persons who are severely immunocompromised due to congenital disease, severe human immunodeficiency virus infection, advanced leukemia or lymphoma, serious malignant disease, treatment with high dose steroids, alkylating agents or antimetabolites or those who receive immunosuppressive therapeutic radiation. These patients were also excluded from this study.

Patient selection and documentation

Patients clinically diagnosed with multiple warts presenting to the dermatology outpatient department of a tertiary care institute were selected after the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Informed consent and assent, if applicable, was obtained before the procedure. The number, size, site, and duration of warts were recorded before treatment and at each follow-up. Documentation of the location, number, and size of warts was done using serial photographs taken under almost the same camera and light settings.

Randomization and blinding

Each patient was assigned an envelope code in the sequence in which they came. Simple randomization was done by drawing chits with treatment codes written on them, i.e., M (for the MMR group) and C (for the C. albicans antigen group). The drawn chits were sealed in opaque envelopes with the envelope code written over them to be opened only at the time of analysis or in the event of an unexpected adverse event. The treatment allotted to the patient was noted down in a separate register allowing the drug provider to ensure that the same drug was being administered in the subsequent visits. Double blinding was ensured during the process.

Treatment and follow-up protocol

Antigens used: C. albicans antigen (CREDISOL® aqueous allergen extract 1:1000 marketed by Creative Drug Industries, Mumbai, Maharashtra) and MMR vaccine (TRESIVAC® marketed by Serum Institute of India Pvt Ltd., Pune, Maharashtra) were used for the study.

Two insulin syringes loaded with 0.15 mL each of either MMR or C. albicans antigen were handed over to the principal investigator by a fellow dermatologist after randomization and allocation concealment. An ice pack was kept over the site before injection to reduce the pain. 0.15 mL of the solution was administered into the substance of each of the two largest warts (total of 0.3 mL per session) at each session. The injections were given at two weekly intervals for a maximum of three sessions (0, 2, and 4 weeks) and followed up at each sitting and 1 month after the last dose. Patients who showed complete resolution of lesions before three injections were followed until the 2nd month after the first injection without any further intralesional injection.

Response assessment and parameters

Response to treatment for treated and untreated warts was reviewed at each visit and during follow-up. For assessing the overall response of a patient to treatment, “No response” was defined as <50% improvement with injections, “Partial response” as 50–99% improvement, and “Complete response” as 100% clearance of warts.

Efficacy was assessed by complete response rate, distal response rate, and response rate of injected warts. Time taken for a complete response was recorded as 2 weeks, 4 weeks, or 8 weeks. The distal response rate was defined as the percentage of improvement of distal warts. Those warts for which no injection was given until the 4th week were considered as distal warts.

Safety was assessed by the rate of adverse events occurring with either of the treatment modalities. The side effects were assessed by the need for post-procedure non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents and the recording of other adverse events, if any.

RESULTS

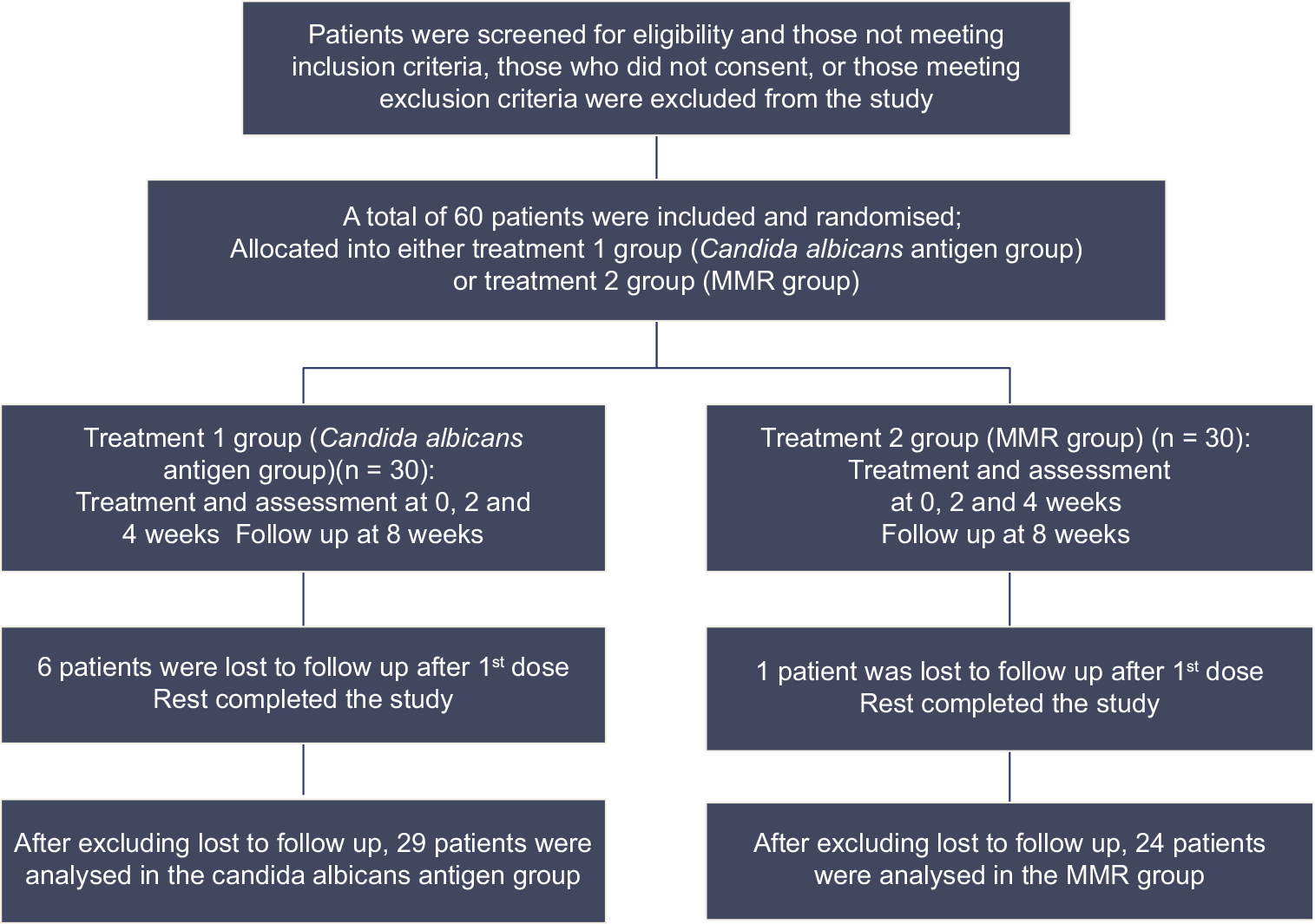

The flow of study participants according to consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) is shown in Figure 1. Per-protocol analysis of the study included 53 patients, after excluding the patients who were lost to follow-up.

- Flow of study participants according to consolidated standards of reporting trials. MMR: Mumps, measles, rubella

The average age of patients included in the study was 29.6 years, with a male-to-female ratio of 3.82:1. The majority of the patients were students (32.08%). The mean duration of warts was 12.58 ± 13.74 months. Most of the patients (73.58%) had warts of <1-year duration. 67.92% of the patients (n = 36) had a previous history of receiving treatment for warts, among which topical salicylic acid was the most common (27.78%) treatment used by patients. Ayurvedic, homeopathic, and home remedies were also commonly used by patients. The mean number of warts per patient in this study was 12.75 ± 10.994. A comparison of the demographic data and wart characteristics showed no significant difference between the two groups [Table 1].

| Treatment group | Test applied | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candida n=24 (%) | MMR n=29 (%) | |||

| Demographic data | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 31.5±10.947 | 28.1±10.798 | Independent t-test | 0.263 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (M) | 20 (83.33) | 22 (75.86) | Chi-square test | 0.502 |

| Female (F) | 4 (16.67) | 7 (24.14) | ||

| M: F | 5:1 | 3.14:1 | ||

| Wart characteristics | ||||

| Duration of warts (months) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 15.21±15.587 | 10.38±11.873 | Mann-Whitney U | 0.325 |

| Previous treatment | ||||

| Yes | 18 (75) | 18 (62.07) | Chi-square test | 0.315 |

| No | 6 (25) | 11 (37.93) | ||

| Number of warts | ||||

| Mean±SD | 13.67±13.144 | 12±9.016 | Mann-Whitney U | 0.900 |

| Type of warts | ||||

| Only common | 10 (41.67) | 11 (37.93) | Fisher’s exact test | 0.752 |

| Only filiform | 7 (29.17) | 5 (17.24) | ||

| Only palmoplantar | 2 (8.33) | 7 (24.14) | ||

| Only periungual | 1 (4.16) | 1 (3.45) | ||

| multiple morphologies | 4 (16.67) | 5 (17.24) | ||

| Sites involved | ||||

| Multiple sites | 7 (29.17) | 11 (37.93) | Chi-square test | 0.502 |

| Only one site | 17 (70.83) | 18 (62.07) | ||

MMR: Measles, mumps, rubella, SD: Standard deviation

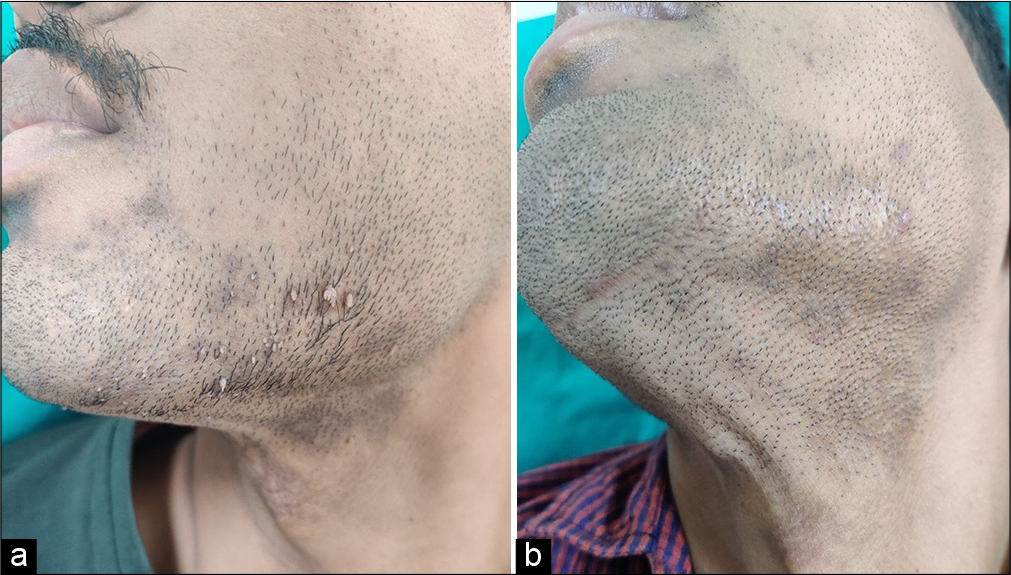

Complete clearance of warts was observed in 34.48% and 37.5% of patients belonging to MMR and Candida groups, respectively [Figures 2 and 3]. A comparison of the overall therapeutic response, response to treatment for injected warts, and distal clearance rates showed no significant difference between the two groups [Table 2]. Complete response was achieved in 30% of the Candida group and 33.3% of the MMR group according to the intention to treat analysis [Table 3].

- A 50-year-old female with multiple warts over dorsum of left foot (a) before immunotherapy with Candida albicans, and (b) at week 8 after intralesional Candida albicans immunotherapy showing complete clearance of both injected and uninjected warts.

- A 27-year-old male with filiform warts over beard area (a) before immunotherapy with MMR, and (b) at week 8 showing complete clearance of both the injected and uninjected warts with intralesional. MMR. MMR: Mumps, measles, rubella.

| Treatment response parameters | Treatment | Total | P-value (Fisher’s exact test) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMR n (%) | Candida n (%) | |||

| Overall response to treatment | ||||

| No response | 16 (55.17) | 13 (54.17) | 29 | 0.955 |

| Partial response | 3 (10.35) | 2 (8.33) | 5 | |

| Complete response | 10 (34.48) | 9 (37.5) | 19 | |

| Response of injected warts | ||||

| No improvement | 15 (51.72) | 13 (54.16) | 28 | 0.908 |

| Partial improvement | 2 (6.9) | 1 (4.17) | 3 | |

| Complete response | 12 (41.38) | 10 (41.67) | 22 | |

| Response of non-injected warts (distal clearance rates) | ||||

| No improvement | 12 (41.38) | 12 (50) | 24 | 0.542 |

| Partial improvement | 7 (24.14) | 3 (12.5) | 10 | |

| Complete response | 10 (34.48) | 9 (37.5) | 19 | |

MMR: Measles, mumps, rubella

| Treatment response parameters | Treatment | Total | P-value (Fisher’s exact test) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMR n(%) | Candidan(%) | ||||

| Overall response to treatment | |||||

| No response | 17 (56.67) | 19 (63.33) | 36 (60) | 0.677 | |

| Partial response | 3 (10) | 2 (6.67) | 5 (8.33) | ||

| Complete response | 10 (33.33) | 9 (30) | 19 (31.67) | ||

| Total | 30 (100) | 30 (100) | 60 (100) | ||

MMR: Measles, mumps, rubella

Among those who achieved complete clearance, the mean time to clearance of warts was 7.20 ± 1.687 weeks in the MMR group and 7.33 ± 2.000 weeks in the Candida group. There was no statistically significant difference with respect to response rates (P = 0.955) and time to complete clearance (P = 0.877) between the two groups. None of the patients who achieved complete clearance had a recurrence of their warts during the 1-month follow-up period. Injection site pain was complained of by all patients. Flu-like symptoms such as shivering or mild headache were observed in 6 patients receiving C. albicans injection (25% of patients in the Candida group). One patient who received a C. albicans injection reported transient erythema. New lesions appeared during treatment and follow-up in 7 patients in each of the MMR and Candida groups. The mean number of new lesions was 2.86 ± 1.952 in the MMR group and 4.14 ± 5.047 in the Candida group, with no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.902). Therapeutic response was found to be relatively higher in children (12–18 years), in those presenting with warts <12 months, and in patients without multiple site involvement. Patients with only palmoplantar warts responded better with either of the two treatment modalities. Patients with filiform warts seemed to respond better with intralesional Candida.

DISCUSSION

The use of various intralesional immunotherapeutic agents for warts, including MMR vaccine and C. albicans antigen has been reported previously with varied success rates. Head-to-head randomized trials (one open labeled9 and two double-blinded10,11) comparing intralesional Candida with MMR showed comparable efficacy of both antigens, similar to our study [Table 4]. However, response rates were higher than ours in these studies, which might be due to the different dosing protocols employed. One open-labeled randomized trial showed significantly better efficacy with Candida when compared to MMR.12

| Author | Study design | Treatment arms | Type of warts treated | N | Dose, interval, max. no: of doses, FU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rageh et al.,12 2020, Egypt | Open-label RCT | MMR, Candida | Refractory or recurrent plantar warts | 60 | 0.3 mL, 3 weekly, Up to 5 doses, 2 month |

| 2 | Nofal et al.,9 2021, Egypt | Open-label RCT | MMR, Candida | Multiple common and plantar warts | 68 | 0.2 mL, 2 weekly, Up to 5 doses |

| 3 | Nofal et al.,10 2021, Egypt | Double-blinded RCT | MMR, Candida, PPD | Periungual warts | 150 | 0.1 mL, 2 weekly, Up to 5 doses, 6 months |

| 4 | Fawzy et al.,11 2020, Egypt | Double-blinded RCT | MMR, Candida, PPD | Multiple plane warts | 120 | 0.1 mL, 2 weekly, Up to 5 doses, 6 month |

| 5 | Our study | Double-blinded RCT | MMR, Candida | Multiple warts | 60 | 0.3 mL, 2 weekly, Up to 3 doses, 1 month |

| Author | Complete cure rate | Side effects | Result | |||

| MMR (%) | Candida(%) | MMR | Candida | |||

| 1 | Rageh et al.,12 2020, Egypt | 26.7 | 80 | Mild pain (16.7%), redness-23.3%, swelling-10%, ecchymoses-6.7% | Mild pain-83.3%, redness-73.3%, swelling-83.3%, flu like symptom-36.6% | Candidasignificantly better |

| 2 | Nofal et al.,9 2021, Egypt | 67.7 | 73.5 | Pain-100%, erythema/edema-20.6%, flu-like symptom-23.5% | Pain-100%, erythema/edema-29.4%, flu-like symptom- 17.6% | No significant difference |

| 3 | Nofal et al.,10 2021, Egypt | 74 | 80 | Pain-100%, erythema/edema-6%, flu-like symptom-4% | Pain-100%, erythema/edema-12%, flu-like symptom- 10% | No significant difference |

| 4 | Fawzy et al.,11 2020, Egypt | 62.5 | 70 | Erythema/edema-10%, flu-like symptom-7.5% | Erythema/edema-12.5%, flu-like symptom-15% | No significant difference |

| 5 | Our study | 34.48 | 37.5 | Pain-100% | Pain-100%, erythema/edema-4%, flu-like symptom-25% | No significant difference |

N: Total number of subjects in the study, RCT: Randomized controlled trial, FU: Follow up, Max: Maximum, MMR: Measles, mumps, rubella, PPD: Purified protein derivative

Pain, erythema, edema, and flu-like symptoms were reported in these studies in both the groups, except in the study by Rageh et al.,12 where flu-like symptoms were not reported with MMR, like in our study. We noted that the flu-like symptoms started 1 h after injection and subsided on their own within 12 h or earlier with NSAIDs. We also observed that the intralesional injection was more painful when injected on plantar and periungual warts. None of the other side effects previously reported with intralesional MMR was observed in our study, thus confirming the safety of this antigen compared to Candida.

The time to achieve complete clearance was 8 weeks in most patients but one patient in the C. albicans group achieved complete clearance with a single injection in our study. A smaller number (n = 4) and shorter duration of wart (1 month) might be the reason for achieving faster clearance for that patient. Signore,8 also observed complete resolution with a single dose of intralesional Candida antigen in 16 out of 44 patients. Kaur et al.,13 noted that there is continuous improvement during the follow-up visits after the last dose of intralesional MMR (3rd dose), with an increase in grade 4 response (more than 76% improvement) from 20% at week 6 (visit for the last dose) to 76.67% at the end of 20 or 24 weeks after the last dose. Similar findings were noted by Saini et al.,14 with an increase in grade 4 response from 4.6% at week 4 (visit of the last dose) to 49.43% at the end of 16 weeks without further injections. This could suggest that the response to immunotherapy is slow and patients can achieve clearance without further injections while maintaining them on follow-up. However, there are no guidelines as to how long the patient should be followed up before considering them as non-responders.

Shaheen et al.,15 noted in their study that the minimum number of sessions needed for complete clearance was two, which was similar to our study where two patients achieved complete clearance within two doses. Majid and Imran,16 observed that patients who failed to show any response with the first or second injection are less likely to show any response with further injections. Although this was true in the majority of patients, 3 patients from the Candida group and 5 patients from the MMR group started to show some response only after the third dose in our study.

Few studies15-19 included only patients with positive immune response to the antigen following an intradermal test before performing intralesional immunotherapy with it. Most of these studies showed a relatively higher clearance rate compared to our study. Both the antigens were administered without presensitization in our study. This approach was practical in our study as carrying out a pre-sensitization test would have increased the number of visits by each patient, affecting compliance.

Placebo-controlled trials on MMR have noted complete response rates of up to 27.5%20-22 in the placebo (saline) group. However, distal clearance rates in all these studies were 0%, suggesting that widespread HPV-targeted immune response cannot be achieved with localized trauma alone. Placebo-controlled trials on Candida have observed complete clearance in 0%,18,23,24 8.6%,25 and 21.2%26 in the control group (saline). Even though we did not have a placebo-control group, our complete response rates and distal clearance rates were higher than those achieved by the placebo group in other studies. This would suggest that the resolution of warts observed in both the groups in our study was due to the effect of antigens and not due to spontaneous resolution or not just due to trauma of the injection eliciting an immune response against HPV.

5 out of the 14 patients who developed new lesions during the course of treatment in both groups achieved complete regression of warts and one patient from the Candida group had a partial clearance of warts within 8 weeks (i.e., the last follow-up visit). This could imply that the development of new lesions during treatment may not be a bad prognostic factor in determining treatment response.

In our study, response to intralesional therapy was better with younger age, shorter duration of warts, and lesser number of warts. Na et al.,27 noted a significant negative correlation of wart clearance with age. Few studies have found a statistically significant negative correlation between the degree of response and duration of warts,15,20,28,29 suggesting that warts having shorter duration are more likely to respond better with treatment. As warts can increase in size and number over time and become more treatment-resistant, early institution of therapy is necessary rather than waiting for spontaneous resolution.15 Furthermore, a longer duration of warts might denote a sort of virus-specific immunodeficiency.15

One of the two patients who had received intralesional MMR in the past and received intralesional Candida in our study had complete resolution of lesions. This might imply that Candida might be a better immunotherapeutic option in instances where intralesional MMR has failed.

There are no strict guidelines for dosing amount, the concentration of Candida antigen, dosing frequency, and duration of intralesional immunotherapy with either of the two antigens used in immunotherapy of warts. It is possible that efficacy would have been higher if the total number of sessions or dose per session or duration of follow-up had been more or if only sensitized subjects were included in the study. Our criteria for categorization of treatment response were more stringent. We had five patients (four in the MMR group and one in the Candida group) with <50% clearance rate who were included under “no response.” Among those patients who had some clearance of warts, we continued our treatment with further injections (up to a total of 5 doses) beyond the last follow-up mandated by the study and observed complete response in them. Furthermore, the difference in the study population selected for treatment, the number of patients, the type and duration of warts, and different brands of the antigen used could be the reasons for this variation in response. These could be the possible reasons for the low percentage of clearance in both treatment modalities.

A shorter follow-up period, the absence of intradermal skin tests with the antigens, and a higher number of patients lost to follow-up in the Candida group compared to the MMR group were the limitations of this study. Previous studies,18,19,27 which reported recurrence with either of the two antigens used, had followed up their study subjects for a period of 6 months after completion of treatment. While there are no specific guidelines regarding the period of follow-up to detect recurrences, it is possible that we would have detected recurrences if we had followed up with our patients longer than 2 months, which we could not because of logistical reasons.

This was a double-blinded randomized trial comparing intralesional MMR with intralesional candida antigen for multiple warts, while the earlier ones were open-label or for periungual or plane warts. Intralesional immunotherapy with Candida and MMR are both effective in the treatment of multiple warts, with comparable overall and distal response rates. Intralesional immunotherapy with MMR was found to be relatively safer than C. albicans antigen.

CONCLUSION

Intralesional MMR can be considered as a first-line therapy in the treatment of multiple warts, and intralesional C. albicans can be considered in patients where intralesional MMR has failed to elicit a favorable response.

Acknowledgment

I (JSR) acknowledge IADVL Academy for the IADVL PG thesis research grant 2020 for the financial support provided to me for this study.

Authors’ contributions

Dr. Satyaki Ganguly conceptualised the study and verified the results, revised the draft and provided final approval. Dr. Jemshi S Rahim collected the data, analysed the data, drafted the article and provided final approval.

Ethical approval

The research/study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur, number AIIMSRPR/IEC/2020/501, dated 17th August, 2020. The Clinical Trials Registry – India (CTRI) trial registration number is CTRI/2020/06/026098.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: This study was financially supported by IADVL postgraduate thesis research grant 2020.

References

- Evolving role of immunotherapy in the treatment of refractory warts. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:364-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intralesional antigen immunotherapy for the treatment of warts: Current concepts and future prospects. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:253-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intralesional immunotherapy for pediatric warts: A review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:265-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immunotherapy of viral warts: Myth and reality. Egypt J Dermatol Venerol. 2015;35:1-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical application of fungus extracts and its culture filtrate in the treatment of skin diseases; 3 Candida vaccine in the treatment of warts (author's transl) Nihon Hifuka Gakkai Zasshi. 1979;89:397-402.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intralesional Candida antigen immunotherapy for the treatment of recalcitrant and multiple warts in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:797-801.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intralesional immunotherapy of common warts: Successful treatment with mumps, measles and rubella vaccine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1166-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candida albicans intralesional injection immunotherapy of warts. Cutis. 2002;70:185-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intralesional measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine versus intralesional Candida antigen in the treatment of common and plantar warts. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:377-83.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intralesional antigen immunotherapy in the treatment of periungual warts. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:286-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intralesional antigen immunotherapy for the treatment of plane warts: A comparative study. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13807.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Intralesional injection of Candida albicans antigen versus measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine for treatment of plantar warts. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2021;30:1-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A Randomized comparative study of MIP and MMR vaccine for the treatment of cutaneous warts. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66:151-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A prospective randomized open label comparative study of efficacy and safety of intralesional measles, mumps, rubella vaccine versus 100% trichloroacetic acid application in the treatment of common warts. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016;4:1529-33.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Intralesional tuberculin (PPD) versus measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine in treatment of multiple warts: A comparative clinical and immunological study. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:194-200.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immunotherapy with intralesional Candida albicans antigen in resistant or recurrent warts: A study. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:360-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immunotherapy in cutaneous warts: Comparative clinical Study between MMR vaccine, tuberculin, and BCG Vaccine. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:2657-66.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intralesional vitamin D3 versus Candida antigen immunotherapy in the treatment of multiple recalcitrant plantar warts: A comparative case-control study. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12997.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comparative study of intralesional vitamin D3 injection and Candida Albicans antigen in treating plantar warts. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:546-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative study of intralesional tuberculin protein purified derivative (PPD) and intralesional measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine for multiple resistant warts. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:868-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic outcome of intralesional immunotherapy in cutaneous warts using the mumps, measles, and rubella vaccine: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:15-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of intralesional injection of mumps-measles-rubella vaccine in patients with wart. Adv Biomed Res. 2014;3:107.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Photodynamic therapy versus Candida antigen immunotherapy in plane wart treatment: A comparative controlled study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2020;32:101973.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intralesional Candida antigen versus intralesional vitamin D3 in the treatment of recalcitrant multiple common warts. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3341-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alternating intralesional purified protein derivative and Candida antigen versus either agent alone in the treatment of multiple common warts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:208-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immunotherapeutic modalities for the treatment of recalcitrant plantar warts: A comparative study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:922-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Two-year experience of using the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine as intralesional immunotherapy for warts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:583-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A study to evaluate the role of intradermal and intralesional measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine in treatment of common warts. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020;11:559-65.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intralesional mumps, measles and rubella vaccine in the treatment of cutaneous warts. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:343-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]